Part 1: The Loveliness

Our beautiful cousins, thus were trees described by the late Carl Sagan in Episode 4 (Heaven and Hell) of his highly praised television series Cosmos. Few would argue with his claim that trees are beautiful. Many others might take issue with his assertion that they are our cousins. There is bountiful evidence that he was correct on both counts.

My first awareness of trees as individuals representing an alien clan, another form of life, came as a child. In our backyard was an apple tree. Its’ low, sprawling limbs were an unspoken but clear invitation to climb. I found that one cannot climb into a tree without becoming aware of bark and texture, leaf and bud, a yielding to the touch. The sensual contact between their skin and ours demands consideration of how we are alike and yet, so different. Gaining age, experience, and strength I proceeded to climb into the maple trees that grew around our homestead. I was thrilled by the new perspective upon the world gained by leaving the ground. To be sure there was also a certain element of risk. To vacate terra firma is to flirt with the ramifications of gravity. But, even as a child, I had the intuitive sense that a world devoid of risks was an exceedingly uninteresting world indeed. One cannot sit high in a tree and remain unaware of being enfolded within a living entity as it surrounds, supports, and shares communion with us.

Growing up in rural Indiana I was surrounded by trees. Granted, the landscape also contained substantial expanses of corn, soy bean, and hay fields. But there were enough patches of woodland left to make the deciduous forest a significant component of my aboriginal world. Though but a child, there were trees enough for me to understand that they were the source of much of my world’s beauty. Now, sixty years later, it is much more difficult to find an unbroken piece of deciduous forest around my home. Here in Sullivan County, all the primal forests have been clear-cut at least once for their timber or pulp. Much forest here has been replaced by farmland. Still more of the forest in this part of southwestern Indiana has been erased from existence by strip-mining. Some of the older mined land, reclaimed with tree plantings, does at least bear a resemblance to the original deciduous forest. But lately the reclamation process causes one to believe they are amongst the rolling grasslands of Kansas rather than the mixed farmlands and woods of the Hoosier state.

Eighty-seven percent of Indiana’s twenty-three million acres was once covered by forest. Today, that figure is about twenty percent. According to the Indiana Dept. of Forestry, there are less than two thousand acres of old growth (> 150 years old) remaining in the state. Less than half of this consists of forests uninfluenced by humans, what we call virgin timber. These remaining old growth plots of forest remind us of what has been lost. Some trees in the recently protected Meltzer Woods in Shelby County and the Wesselman Woods Nature Preserve in Vanderburgh County are thought to be four hundred years old. I find that expanse of time difficult to grasp. Such trees were standing impressively large when the Revolutionary War with Great Britain was fought. The great lifespan of many trees is, I suppose, one of the attributes that draws me to them in near worshipful admiration. Our human existence, measured in decades, seems mighty puny compared to that of a tree such as a bristlecone pine that was laying down wood six centuries before Tutankhamun ascended the throne of ancient Egypt.

Eighty-seven percent of Indiana’s twenty-three million acres was once covered by forest. Today, that figure is about twenty percent. According to the Indiana Dept. of Forestry, there are less than two thousand acres of old growth (> 150 years old) remaining in the state. Less than half of this consists of forests uninfluenced by humans, what we call virgin timber. These remaining old growth plots of forest remind us of what has been lost. Some trees in the recently protected Meltzer Woods in Shelby County and the Wesselman Woods Nature Preserve in Vanderburgh County are thought to be four hundred years old. I find that expanse of time difficult to grasp. Such trees were standing impressively large when the Revolutionary War with Great Britain was fought. The great lifespan of many trees is, I suppose, one of the attributes that draws me to them in near worshipful admiration. Our human existence, measured in decades, seems mighty puny compared to that of a tree such as a bristlecone pine that was laying down wood six centuries before Tutankhamun ascended the throne of ancient Egypt.

But all is not lost. We still have substantial areas of forest in the eastern United States (and the west of course). We have done some recovering since the days around the turn of the 20th century when eastern forests were being cleared at the rate of thirteen and a half square miles per day. In fact, according to a report from The Forest History Society, over two-thirds of our nation’s area which was forested in 1600 is still covered by woodlands of various types today. Of course, due to a history of clearing for farming, use for fuel and charcoal, and timber production, these forests differ substantially from what they were in the 17th Century. Although I still see trees, I am often reminded of Aldo Leopold’s observation that, “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.”

To sense what the virgin forests of Indiana must have been like, one must search out the few remaining tracts. My own familiarity with such an undisturbed, old growth forest comes from visits to Donaldson Woods  Nature Preserve located in Spring Mill State Park in Lawrence County, Indiana. The few pieces of old forest that remain in Indiana persist thanks to individuals who simply couldn’t bear to see these beautiful woodlands destroyed. Whether their reasons were allied to a sense of historical preservation, sentimentality, or even spirituality I do not know. I do know that I owe them a great debt of gratitude for making it possible for me to experience a primordial piece of our natural world. For this particular 67 acres of woodland we owe thanks to the unconventionality of George Donaldson who immigrated to Indiana from Scotland just after the civil war. In a time when the conformist wisdom called for one to market one’s timber and establish a farm Donaldson resisted. As Scott Russell Sanders has noted in his book A Conservationist Manifesto, Donaldson, . . . made no use of the land at all, except to walk around and admire it. No wood cutting, no hunting, no extraction of limestone; these were his rules. Thanks to these guidelines I can now wander through a living museum of natural history, a vestigial portion of Indiana as it existed in pre-settlement times.

Nature Preserve located in Spring Mill State Park in Lawrence County, Indiana. The few pieces of old forest that remain in Indiana persist thanks to individuals who simply couldn’t bear to see these beautiful woodlands destroyed. Whether their reasons were allied to a sense of historical preservation, sentimentality, or even spirituality I do not know. I do know that I owe them a great debt of gratitude for making it possible for me to experience a primordial piece of our natural world. For this particular 67 acres of woodland we owe thanks to the unconventionality of George Donaldson who immigrated to Indiana from Scotland just after the civil war. In a time when the conformist wisdom called for one to market one’s timber and establish a farm Donaldson resisted. As Scott Russell Sanders has noted in his book A Conservationist Manifesto, Donaldson, . . . made no use of the land at all, except to walk around and admire it. No wood cutting, no hunting, no extraction of limestone; these were his rules. Thanks to these guidelines I can now wander through a living museum of natural history, a vestigial portion of Indiana as it existed in pre-settlement times.

It is the size of the trees that, to me, makes Donaldson Woods so special. In the second growth forest around my home, I am lucky to find a tree greater than two feet or so in diameter. The virgin timber in Donaldson Woods includes yellow poplar and white oaks nearly six feet in diameter at breast height. There are American beech trees nearly three feet across. Shagbark hickory and sugar maple, sycamore and ash are here too; all standing with  their most impressive bearing. Towering well over one hundred feet in height, they are mighty impressive representatives of their kind. While passing beneath these giants, I am reminded of Tolkien’s forests: Fangorn, Mirkwood, Lothlorien – old beyond guessing, massive of limb, immense of trunk, towering upward through the dappled sunlight, leafy canopies forming a living roof above the head. In spring the understory of this wondrous place is dappled with dogwood white and the rosy purple of redbuds. The forest floor is colored by the virginal white of bloodroot, the ornate purple of violets, the azure blue of Virginia bluebells, the gaudy yellow of dogtooth violets,. Of course this forest is a system not just a collection of trees and herbs. And so the scene is made even more vibrant by the chatter of gray squirrels, the repetitious bird-like chips of the chipmunk, the brash kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk of a pileated woodpecker, and the poignantly liquid soliloquy of a wood thrush.

their most impressive bearing. Towering well over one hundred feet in height, they are mighty impressive representatives of their kind. While passing beneath these giants, I am reminded of Tolkien’s forests: Fangorn, Mirkwood, Lothlorien – old beyond guessing, massive of limb, immense of trunk, towering upward through the dappled sunlight, leafy canopies forming a living roof above the head. In spring the understory of this wondrous place is dappled with dogwood white and the rosy purple of redbuds. The forest floor is colored by the virginal white of bloodroot, the ornate purple of violets, the azure blue of Virginia bluebells, the gaudy yellow of dogtooth violets,. Of course this forest is a system not just a collection of trees and herbs. And so the scene is made even more vibrant by the chatter of gray squirrels, the repetitious bird-like chips of the chipmunk, the brash kuk-kuk-kuk-kuk of a pileated woodpecker, and the poignantly liquid soliloquy of a wood thrush.

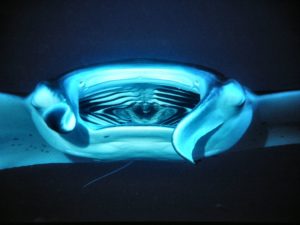

Being an ecosystem of ancient and rich texture, this old grow forest also carries out a host of activities not visible to the human eye. I was once clearly reminded of this when I took one of my biology classes on a visit to Donaldson Woods. Why, asked one of my students, don’t the trees form a pit beneath themselves as they use up more and more of the soil in which they grow? What a great question! Why not indeed? It seems logical, since trees are so firmly rooted in their place, to imagine them carrying more and more of the soil’s components up into their tissues. In fact, this very question was of great interest by at least the year 1648. It was at this time that the Belgian scientist Jan Baptista van Helmont undertook to discover whether or not trees were “eating” the soil so to speak in order to accomplish their growth.

This is how van Helmont conducted his experiment. Into a container  holding two hundred pounds of soil he placed a willow sapling. Over the next five years he watered the tree. At the end of this period of time, he removed the tree from the soil and weighed it. At the beginning of his experiment, the willow had weighed five pounds; now its weight was one hundred and sixty-nine pounds. van Helmont then weighed the soil in the container and found that it had lost only two ounces of weight. Since he had done nothing but water the plant, van Helmont concluded that the one hundred and sixty-four pounds of tissue formed by the tree had come only from the water he had supplied. Unknowingly, Jan van Helmont had germinated the beginnings of our understanding of photosynthesis; the process which makes it possible for most of the life on earth to exist.

holding two hundred pounds of soil he placed a willow sapling. Over the next five years he watered the tree. At the end of this period of time, he removed the tree from the soil and weighed it. At the beginning of his experiment, the willow had weighed five pounds; now its weight was one hundred and sixty-nine pounds. van Helmont then weighed the soil in the container and found that it had lost only two ounces of weight. Since he had done nothing but water the plant, van Helmont concluded that the one hundred and sixty-four pounds of tissue formed by the tree had come only from the water he had supplied. Unknowingly, Jan van Helmont had germinated the beginnings of our understanding of photosynthesis; the process which makes it possible for most of the life on earth to exist.

Biologists now know that it is not from water alone that green plants build their tissues of root, stem, and leaf. A succession of experiments over the next century or so eventually elucidated the process of photosynthesis. It has been found that much of the water taken up by plants is transpired from their leaves. Each molecule of water leaving the stoma of a leaf exerts a forceful tug upon the train of water molecules extending back down the tree to the roots. This is part of the mechanism which pulls water molecules upward in a plant in the absence of a pump (heart).

Scientists also eventually understood that the gas carbon dioxide was of extreme importance in the photosynthetic process. Additionally, the necessity of sunlight for the occurrence of photosynthesis was revealed. One might summarize this incredibly complex series of biochemical reactions thusly. Green plants (the green pigment chlorophyll is necessary too) take up water from the soil via their roots and take carbon dioxide from the air through pores in their leaves. In the presence of sunlight (a source of energy to drive the process) plants rip apart some of the water and the carbon dioxide molecules. They now have a supply of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms; basic elements for building organic compounds. We might compare this to tearing down an old barn and reusing the weathered boards and timbers to construct a recreational cabin.

By rearranging these elements and adding a sprinkle of ingredients from the soil, such as nitrates, plants are able to build sugars, starches, oils, and proteins. These compounds are then used to construct the tissues from which stems, leaves, roots, and flowers are made. Oxygen gas is given off as a byproduct of photosynthesis and is used by animals as a respiratory fuel. They in turn exhale carbon dioxide which can be taken up by plants for use in photosynthesis. A miraculous balancing act this is and one which, along with photosynthesis’s mirror image process cell respiration, keeps most of the living world chugging along. And this, prized student, is why the trees in Donaldson Woods do not “eat” the soil beneath their feet.

6H2O + 6CO2 —–———–> C6H12O6 + 6O2

Thus would I submit that trees are not only beautiful in form with their noble trunks, their robust branches, their luxuriant leaves of emerald, olive, and jade; they are also of inordinate exquisiteness in function. Not eaters of the soil but eaters of the sun they are. Each leaf is a tiny solar array capable of capturing light energy and transforming it into energy of chemical form. Having made this energy transformation, the tree is now able to perform a biochemical sleight of hand of staggering complexity. By building the aforementioned organic compounds, proteins and such, the tree is now able to make wood and meristem, cambium and bark, xylem and phloem, mesophyll and chloroplast.

A magnificent poplar or oak, standing tall and solid, is made essentially from carbon dioxide gas and water. Imagine if we could do that. Doubtless a skin of green might take some getting used to but we could subsist solely on a few hours of sunbathing or sitting beneath a grow-light each day. Adding the occasional glass of water, and perhaps a multivitamin we could convert light energy into food and tissue – automatic, effortless, wondrous. So it is with the trees, wondrous in both form and function.

Part 2: The Relationship

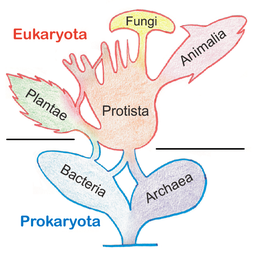

But recall that Carl Sagan referred to trees not just as beings of great beauty. He also denoted them as our cousins. Is this possible? A cousin is often defined loosely as a thing related to another. We might think of the ukulele and the guitar as cousins for example. But, in the case of the trees, Sagan meant something more akin to our notion of a cousin as a member of our extended family; an actual relative by descent. Should we, could we think of trees in this way? There is plentiful biological evidence to suggest that Sagan was without question correct.

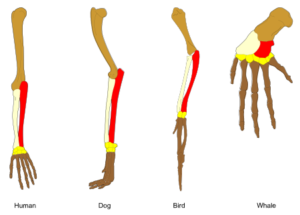

When humans first began to categorize the relationships of organisms, in what we might think of as an observational, scientific manner, the criteria for classification were broad. Animals might, for example, be classified as blooded or bloodless, or as creatures of the air, land, or water. As science progressed, it didn’t take long for astute observers to notice that lumping organisms such as fish, whales, and ducks into a group because they inhabited water was a highly inaccurate measure of their real relationships. Enlightened taxonomists such as Linnaeus, Owen, and Cuvier turned to similarities and differences in anatomical structure as the keystone to understanding taxonomic relationships among organisms. For example, looking at forelimb structure (humerus, ulna, radius, carpals, metacarpals, phalanges) allowed the insight that mammals such as humans and whales are actually more closely related than whales and fish.

The same insight into our relationship with trees, and other plants, can be reasoned. At the cellular level, cells being the basic structural unit of living things, we find that plants and humans both possess a plasma membrane, nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and ribosomes as well as certain other structures.

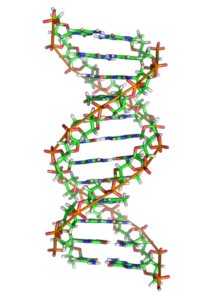

We can go even farther. It is known that these structures arise because organisms have the instructions for building cells and their organelles encoded in their DNA. Cells build tissues, tissues comprise organs, organs create organ systems, organ systems function to form and sustain an organism. DNA is passed from ancestors to descendants. Back through the  generations our DNA exists as an immortal thread connecting us with our deepest ancestry, linking us with the very origins of life on our planet. DNA analysis has become a powerful tool in fighting crime, proving paternity, and demonstrating our ancestry. The same biotechnological logic provides potent evidence of our relationship with the trees.

generations our DNA exists as an immortal thread connecting us with our deepest ancestry, linking us with the very origins of life on our planet. DNA analysis has become a powerful tool in fighting crime, proving paternity, and demonstrating our ancestry. The same biotechnological logic provides potent evidence of our relationship with the trees.

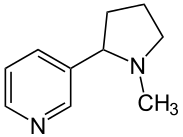

Beneath the skin, beneath the bark, written in the coded A’s, T’s, G’s, and C’s of our nucleotides lies the irrefutable proof of our kinship with oak and maple, redwood and sequoia. When comparing a snippet of the DNA sequence in a gene from a human – tct cca ccc tca ttt gat gac cgc aga – with that from an oak – tcc aca acc ctt tct gta ttc att cct – one is struck not by the strangeness of their differences but by the familiarity of their likenesses. A similar unity can be seen when we compare the DNA of any two organisms we might choose. The genetic code, which continues to surprise us with its complexity and dynamism, bears convincing evidence of the unity of all life. After all, organisms receive this wondrous code from their ancestors.

And so my friends, I hope you are fortunate enough to one day find yourself standing in the cathedral that we call Donaldson Woods, the basilica of Muir Woods, or the sanctuary known as Sequoia National Park. I hope you are able to someday find yourself sniffing a hint of vanilla within a stand of ponderosa pine in our American west. I wish you are granted the opportunity to paddle your canoe through a virgin cypress swamp whose trees were young when the first Europeans sailed the Atlantic. If you are granted these boons, perhaps you too will find yourself immersed in a sense of enraptured delight as you marvel at the beauty of our cousins the trees.

Photo Credits: van Helmont statue - Henxter at WikimediaCommons limb homology - Wikipedia.com DNA molecule - Richard Wheeler at WikimediaCommons All other photos by the author.

.

millimeters in length, 20 millimeters in height, 15 millimeters in width, and a ghostly white in color was this piece of inorganic poetry. It was the phalangeal bone of a white-tailed deer, a toe bone. How it came to be there all alone on that square foot of woodland floor was a puzzle. How it had achieved its perfection of form presented me an even greater mystery.

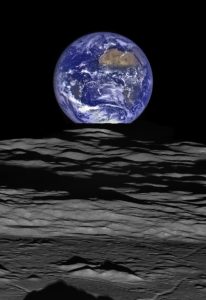

millimeters in length, 20 millimeters in height, 15 millimeters in width, and a ghostly white in color was this piece of inorganic poetry. It was the phalangeal bone of a white-tailed deer, a toe bone. How it came to be there all alone on that square foot of woodland floor was a puzzle. How it had achieved its perfection of form presented me an even greater mystery. self-replicating compound of extraordinary control, amazing elasticity, and astonishing potential. It is the shared strand that has been passed from generation to generation up through the branches of the biosphere’s phylogenetic tree. In this way, DNA weaves all life into the quilt we call biodiversity. Our small, blue world is such an extraordinarily special place – so beautiful, so enriched by its distinctive life forms, so

self-replicating compound of extraordinary control, amazing elasticity, and astonishing potential. It is the shared strand that has been passed from generation to generation up through the branches of the biosphere’s phylogenetic tree. In this way, DNA weaves all life into the quilt we call biodiversity. Our small, blue world is such an extraordinarily special place – so beautiful, so enriched by its distinctive life forms, so  unique within the cosmos.

unique within the cosmos.

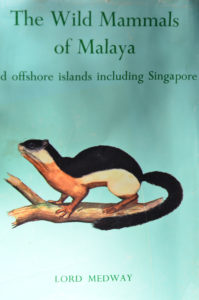

Corps-Smithsonian Institution Environmental Program. In Malaysia I worked as a vertebrate zoology lecturer in the biology department of the University of Agriculture (today’s Universiti Putra Malaysia). At that time, the university was rapidly expanding

Corps-Smithsonian Institution Environmental Program. In Malaysia I worked as a vertebrate zoology lecturer in the biology department of the University of Agriculture (today’s Universiti Putra Malaysia). At that time, the university was rapidly expanding  in both enrollment and physical size. Many of the biology department staff members were away in the U.S., Australia, or Great Britain pursuing advanced degrees. Peace Corps volunteers filled the void within the department until these folks returned from their graduate school experience.

in both enrollment and physical size. Many of the biology department staff members were away in the U.S., Australia, or Great Britain pursuing advanced degrees. Peace Corps volunteers filled the void within the department until these folks returned from their graduate school experience.

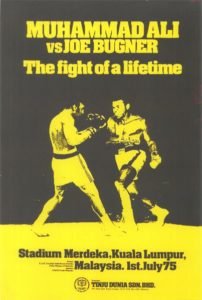

Lumpur preparing for a fight with his British opponent Joe Bugner. Ali was tremendously popular in Malaysia where the state religion is Islam. The boxer had a huge entourage with him and the group occupied an entire floor of the Kuala Lumpur Hilton. His stay was marked by the accoutrements of stardom and his sorties to the training arena announced by siren-blaring police escorts.

Lumpur preparing for a fight with his British opponent Joe Bugner. Ali was tremendously popular in Malaysia where the state religion is Islam. The boxer had a huge entourage with him and the group occupied an entire floor of the Kuala Lumpur Hilton. His stay was marked by the accoutrements of stardom and his sorties to the training arena announced by siren-blaring police escorts. (photo by Mundo Gump at Wikimedia Commons)

(photo by Mundo Gump at Wikimedia Commons) the University of Agriculture Malaysia or the Universiti Pertanian as it was then called. As soon as possible, I began to go on birding walks, make scouting forays for frogs, lizards, and snakes and peruse the literature on Malaysian mammals. All this was necessary because I would soon begin work as a lecturer in vertebrate zoology at the university. I needed to bring myself up to some degree of working knowledge regarding the local fauna and be quick about it.

the University of Agriculture Malaysia or the Universiti Pertanian as it was then called. As soon as possible, I began to go on birding walks, make scouting forays for frogs, lizards, and snakes and peruse the literature on Malaysian mammals. All this was necessary because I would soon begin work as a lecturer in vertebrate zoology at the university. I needed to bring myself up to some degree of working knowledge regarding the local fauna and be quick about it. specimen would be produced, a Malayan pangolin and a leopard cat for example. Although I remember many of these animals with fond aesthetic and scholarly interest, my recollection of the first Malaysian cobra I received stands out as a most unforgettable experience.

specimen would be produced, a Malayan pangolin and a leopard cat for example. Although I remember many of these animals with fond aesthetic and scholarly interest, my recollection of the first Malaysian cobra I received stands out as a most unforgettable experience. disturbing manifestations of neural paralysis such as drooping of the eyelids, drooling, numbness, tingling of the skin, and euphoria. These may escalate into truly life-threatening signs such as difficulty in breathing, shock, and respiratory failure. The effect of neurotoxins on the respiratory system has been likened to having another person sit on one’s chest while trying to breathe. Perhaps you will now understand why I looked forward to getting the captive cobra from the bag with some trepidation.

disturbing manifestations of neural paralysis such as drooping of the eyelids, drooling, numbness, tingling of the skin, and euphoria. These may escalate into truly life-threatening signs such as difficulty in breathing, shock, and respiratory failure. The effect of neurotoxins on the respiratory system has been likened to having another person sit on one’s chest while trying to breathe. Perhaps you will now understand why I looked forward to getting the captive cobra from the bag with some trepidation. forward, I immobilized its head with downward pressure applied across the parietal scales. With studious intent, I carefully placed my index finger on top of the head, thumb and middle finger just behind the skull and the cobra was secured. Supporting its body with my other hand, the specimen was carefully deposited into a cloth snake bag. This in itself was a critical step. If not cautious, or by using a snake bag too small for its occupant, one can be quickly confronted by a snake bent on escape which has used its tail, and its length, to spring right back out of the bag. With the container secured, I then moved the snake upstairs to my office where it was confined in a secure terrarium.

forward, I immobilized its head with downward pressure applied across the parietal scales. With studious intent, I carefully placed my index finger on top of the head, thumb and middle finger just behind the skull and the cobra was secured. Supporting its body with my other hand, the specimen was carefully deposited into a cloth snake bag. This in itself was a critical step. If not cautious, or by using a snake bag too small for its occupant, one can be quickly confronted by a snake bent on escape which has used its tail, and its length, to spring right back out of the bag. With the container secured, I then moved the snake upstairs to my office where it was confined in a secure terrarium. the cobra silently opened its mouth. Quickly, like jets from a pair of miniature squirt guns, two streams of venom shot against the terrarium’s glass. Cobras are well able to fixate on the face of an aggressor and aim the venom toward the eyes. Such was the case here and I welcomed the intervening glass. This type of behavior continued for the first couple of days of captivity. Any approach to the terrarium elicited a violent response. In the interim periods, when I worked at my desk, I would occasionally be seized by that odd feeling of being watched which we sometimes experience. Glancing over my shoulder at the terrarium, I would see the cobra silent, immobile but erect as a candle stick watching my movements. Even from across the room, motions of my hands or body would send the snake into an instant defensive posture and there it would stand unwavering, its gaze fixed upon me.

the cobra silently opened its mouth. Quickly, like jets from a pair of miniature squirt guns, two streams of venom shot against the terrarium’s glass. Cobras are well able to fixate on the face of an aggressor and aim the venom toward the eyes. Such was the case here and I welcomed the intervening glass. This type of behavior continued for the first couple of days of captivity. Any approach to the terrarium elicited a violent response. In the interim periods, when I worked at my desk, I would occasionally be seized by that odd feeling of being watched which we sometimes experience. Glancing over my shoulder at the terrarium, I would see the cobra silent, immobile but erect as a candle stick watching my movements. Even from across the room, motions of my hands or body would send the snake into an instant defensive posture and there it would stand unwavering, its gaze fixed upon me. often replace them after a period of time. Like the cobra I encountered, they simply lose interest in performing and refuse to rise from the charmer’s basket.

often replace them after a period of time. Like the cobra I encountered, they simply lose interest in performing and refuse to rise from the charmer’s basket. don’t deserve the fear many people experience should they come upon one of them.

don’t deserve the fear many people experience should they come upon one of them.

It was a mixed band of squirrel monkeys and saddle-back tamarins that had attracted my attention. Up ahead I could see their swift movements among the branches of a towering Inga tree. The calls of these

It was a mixed band of squirrel monkeys and saddle-back tamarins that had attracted my attention. Up ahead I could see their swift movements among the branches of a towering Inga tree. The calls of these  little primates could easily be mistaken for the vocalizations of birds. In fact, it was their calling that had originally drawn my attention to the tree they were exploring. This tree was located only a few hundred yards from the majestic Amazon River in northeastern Peru. Here the Neotropical rainforest presented a most splendid exhibit of biodiversity. I was walking within a forest which held ten percent of the world’s plant species. Dispersed on and beneath the impressive community of forest giants – kapok, fig, pacay, Brazil nut – lived a multitudinous assemblage of fungi, insects, spiders, frogs, lizards, snakes, birds, and mammals. Stepping along the trail toward the little primates, I squeezed through a rich undergrowth of ginger, irapay and pona palm, philodendron, melastoma, and maranta. Although the comparison is shopworn, it really was akin to walking within a crowded greenhouse. In the background I heard the periodic calls of screaming piha’s. The piercing, exotic whistles of these rather nondescript, grayish brown birds cried out to me – “rainforest, this is tropical rainforest”. (You can hear one at the following link.)

little primates could easily be mistaken for the vocalizations of birds. In fact, it was their calling that had originally drawn my attention to the tree they were exploring. This tree was located only a few hundred yards from the majestic Amazon River in northeastern Peru. Here the Neotropical rainforest presented a most splendid exhibit of biodiversity. I was walking within a forest which held ten percent of the world’s plant species. Dispersed on and beneath the impressive community of forest giants – kapok, fig, pacay, Brazil nut – lived a multitudinous assemblage of fungi, insects, spiders, frogs, lizards, snakes, birds, and mammals. Stepping along the trail toward the little primates, I squeezed through a rich undergrowth of ginger, irapay and pona palm, philodendron, melastoma, and maranta. Although the comparison is shopworn, it really was akin to walking within a crowded greenhouse. In the background I heard the periodic calls of screaming piha’s. The piercing, exotic whistles of these rather nondescript, grayish brown birds cried out to me – “rainforest, this is tropical rainforest”. (You can hear one at the following link.) I listened as a continuous series of high-pitched squeaks, trills, and

I listened as a continuous series of high-pitched squeaks, trills, and  staccato screeches produced by the busy monkeys issued from the trees just ahead of me. Lifting my binoculars to my eyes, I once again scanned ahead and saw that the roving assemblage was much closer now. I could clearly make out individual animals within the primate band. If I could only get a little nearer I would really be able to observe their behavior. Lowering my binoculars, I began to move closer to the little animals. With one foot thus poised in mid-stride, there suddenly came to me a second thought. The how or why of this sudden, unbidden neuronal signal has puzzled me for many years. Whatever the source, there abruptly arose in my mind a delicate warning. Be careful it said. Watch where you step it whispered. Heeding this cautioning counsel without question, I glanced down at the trail. Lying there, directly in the path of my next step, was a snake. My heart made a sudden lunge into a higher gear. This was not just any snake. Resting there at my feet, its head slightly raised from the ground in alertness was a fer-de-lance, considered by many to be the most dangerously venomous snake in the Neotropics.

staccato screeches produced by the busy monkeys issued from the trees just ahead of me. Lifting my binoculars to my eyes, I once again scanned ahead and saw that the roving assemblage was much closer now. I could clearly make out individual animals within the primate band. If I could only get a little nearer I would really be able to observe their behavior. Lowering my binoculars, I began to move closer to the little animals. With one foot thus poised in mid-stride, there suddenly came to me a second thought. The how or why of this sudden, unbidden neuronal signal has puzzled me for many years. Whatever the source, there abruptly arose in my mind a delicate warning. Be careful it said. Watch where you step it whispered. Heeding this cautioning counsel without question, I glanced down at the trail. Lying there, directly in the path of my next step, was a snake. My heart made a sudden lunge into a higher gear. This was not just any snake. Resting there at my feet, its head slightly raised from the ground in alertness was a fer-de-lance, considered by many to be the most dangerously venomous snake in the Neotropics.

sion flowers, the heliconias, torch

sion flowers, the heliconias, torch  ginger, and the myriad species of orchids. Here at home, I am captivated by the loveliness of spring beauty and Dutchman’s breeches, catalpa and Virginia bluebell, Silphium and blazing star. They all seem to go beyond the bounds of practicality. The rich diversity of colors,

ginger, and the myriad species of orchids. Here at home, I am captivated by the loveliness of spring beauty and Dutchman’s breeches, catalpa and Virginia bluebell, Silphium and blazing star. They all seem to go beyond the bounds of practicality. The rich diversity of colors,  shadings, crenellations, and flamboyancy seem to defy all reason.

shadings, crenellations, and flamboyancy seem to defy all reason. serve as sufficient camouflage within the middle layers of the rainforest. But no, this extraordinary cat is covered in a myriad of blotches of multitudinous shades from white to gray, fawn to black, sand to sepia. Arranged in a bedazzling array of smudges, spots, ovals, oblongs, and squares their coat renders them nearly invisible within their tropical forest home. But I can’t help but perceive that the pattern of their coat goes well beyond the bounds of a super-efficient camouflage. I cannot look at a clouded leopard and not find myself stunned by its absolutely exquisite beauty. I invariably feel a visceral emotion that is totally divorced from my understanding of the biological mechanisms which bring about this beauty. I dare say the feeling is more akin to the sensation I receive when contemplating an impressionist painting or listening to the opening strains of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major.

serve as sufficient camouflage within the middle layers of the rainforest. But no, this extraordinary cat is covered in a myriad of blotches of multitudinous shades from white to gray, fawn to black, sand to sepia. Arranged in a bedazzling array of smudges, spots, ovals, oblongs, and squares their coat renders them nearly invisible within their tropical forest home. But I can’t help but perceive that the pattern of their coat goes well beyond the bounds of a super-efficient camouflage. I cannot look at a clouded leopard and not find myself stunned by its absolutely exquisite beauty. I invariably feel a visceral emotion that is totally divorced from my understanding of the biological mechanisms which bring about this beauty. I dare say the feeling is more akin to the sensation I receive when contemplating an impressionist painting or listening to the opening strains of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major. sheer elegance of form what could surpass the stealthily wading great egret or the striding black-necked stilt? What figures in motion are more graceful than the dynamic soaring of a wandering albatross or the lazy circling of a red-tailed hawk riding upon its invisible donut of air? Should we want to rank the beauty of

sheer elegance of form what could surpass the stealthily wading great egret or the striding black-necked stilt? What figures in motion are more graceful than the dynamic soaring of a wandering albatross or the lazy circling of a red-tailed hawk riding upon its invisible donut of air? Should we want to rank the beauty of  birds based upon their color, we might find that this too is not so simple. The colors and forms exhibited among the Aves seem nearly infinite. How could I hope to choose a winner from among the likes of Tanzania’s lilac-breasted roller, Costa Rica’s resplendent quetzal, our American wood duck, Malaysia’s Argus

birds based upon their color, we might find that this too is not so simple. The colors and forms exhibited among the Aves seem nearly infinite. How could I hope to choose a winner from among the likes of Tanzania’s lilac-breasted roller, Costa Rica’s resplendent quetzal, our American wood duck, Malaysia’s Argus  pheasant, or Peru’s masked trogon? Though I understand the adaptive nature of beak, wing and leg, I still cannot fully fathom why I am compelled to stare at such birds in dumbstruck reverence.

pheasant, or Peru’s masked trogon? Though I understand the adaptive nature of beak, wing and leg, I still cannot fully fathom why I am compelled to stare at such birds in dumbstruck reverence. fact that it is an animal of great esthetic beauty. Lying quietly upon a bed of leaves, this serpent becomes virtually invisible. The rich mixture of browns, blacks, fawns, yellows, creams, and whites are arranged in an intricate pattern of blotches, rectangles, and leafy shapes that make it astonishingly difficult to distinguish. Looking upon one of these snakes, I must convince myself that an artist of supreme skill has not surreptitiously sneaked into the reptile house by night and completed a marvelous job of body painting

fact that it is an animal of great esthetic beauty. Lying quietly upon a bed of leaves, this serpent becomes virtually invisible. The rich mixture of browns, blacks, fawns, yellows, creams, and whites are arranged in an intricate pattern of blotches, rectangles, and leafy shapes that make it astonishingly difficult to distinguish. Looking upon one of these snakes, I must convince myself that an artist of supreme skill has not surreptitiously sneaked into the reptile house by night and completed a marvelous job of body painting most beautiful contest. Rainbow trout, rainbow darter, clown triggerfish, dolphinfish, Achilles tang, lion fish, angel fish, and Moorish idol. How could I

most beautiful contest. Rainbow trout, rainbow darter, clown triggerfish, dolphinfish, Achilles tang, lion fish, angel fish, and Moorish idol. How could I choose from this kaleidoscopic of blues, greens, yellows, oranges, reds, and golds? Scientifically, rationally we know that the color patterns of these fishes may serve to camouflage, to distinguish sexes, to identify a species. But do their

choose from this kaleidoscopic of blues, greens, yellows, oranges, reds, and golds? Scientifically, rationally we know that the color patterns of these fishes may serve to camouflage, to distinguish sexes, to identify a species. But do their  colors really have to be so varied, their forms so diverse, their hues so subtle, and their shades so delicate? Something tells me they do not.

colors really have to be so varied, their forms so diverse, their hues so subtle, and their shades so delicate? Something tells me they do not. subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead.” The essence responsible for the unquantifiable quality of the north woods Leopold called the noumenon of material things. It stands in opposition to a phenomenon, something that is concrete and subject to empirical study. Could it be that complexity, diversity, and beauty are reflections of the noumenon that generates the sense of awe we often experience in the natural world? Is it this noumenon, this unquantifiable presence that compel s us to experience with an emotion akin to religious awe a soaring flock of cranes, a flowering prairie, the north woods?

subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead.” The essence responsible for the unquantifiable quality of the north woods Leopold called the noumenon of material things. It stands in opposition to a phenomenon, something that is concrete and subject to empirical study. Could it be that complexity, diversity, and beauty are reflections of the noumenon that generates the sense of awe we often experience in the natural world? Is it this noumenon, this unquantifiable presence that compel s us to experience with an emotion akin to religious awe a soaring flock of cranes, a flowering prairie, the north woods? Van Horn’s view. Within that essay lies this passage. “I heard of a boy once who was brought up an atheist. He changed his mind when he saw that there were a hundred-odd species of warblers, each bedecked like to the rainbow. . . No fortuitous concourse of elements working blindly through any number of millions of years could account for why warblers are so beautiful. No mechanistic theory . . . has ever quite answered for the colors of the cerulean warbler, or the vespers of the wood thrush, or the swansong, or goose music”. Leopold ended his ruminations upon the boy who came to believe with these words. “There are yet many boys to be born who, like Isaiah, may see, and know and consider, and understand together, that the hand of the Lord hath done this.”

Van Horn’s view. Within that essay lies this passage. “I heard of a boy once who was brought up an atheist. He changed his mind when he saw that there were a hundred-odd species of warblers, each bedecked like to the rainbow. . . No fortuitous concourse of elements working blindly through any number of millions of years could account for why warblers are so beautiful. No mechanistic theory . . . has ever quite answered for the colors of the cerulean warbler, or the vespers of the wood thrush, or the swansong, or goose music”. Leopold ended his ruminations upon the boy who came to believe with these words. “There are yet many boys to be born who, like Isaiah, may see, and know and consider, and understand together, that the hand of the Lord hath done this.” atrophy until only a stump remains. The isopod remains attached to the muscles of this stub and begins to actually function as the fish host’s tongue. The tongue-eating isopod, how macabre is that? I’m sure glad it doesn’t have a taste for humans. It would put a whole new spin on accidentally getting a mouthful of seawater while swimming wouldn’t it?

atrophy until only a stump remains. The isopod remains attached to the muscles of this stub and begins to actually function as the fish host’s tongue. The tongue-eating isopod, how macabre is that? I’m sure glad it doesn’t have a taste for humans. It would put a whole new spin on accidentally getting a mouthful of seawater while swimming wouldn’t it? enlargement of body regions can be so extreme as to inhibit mobility. Deformity of this sort requires repeated infection with the microfilarial worm Wuchereria over a period of years. Fortunately, although nearly fifteen percent of the human population lives in areas where elephantiasis is endemic, such extreme cases are rare. Anecdotally, during the three years I lived in Southeast Asia, I actually saw only one case of this disease and the person afflicted exhibited only a slight swelling of one leg.

enlargement of body regions can be so extreme as to inhibit mobility. Deformity of this sort requires repeated infection with the microfilarial worm Wuchereria over a period of years. Fortunately, although nearly fifteen percent of the human population lives in areas where elephantiasis is endemic, such extreme cases are rare. Anecdotally, during the three years I lived in Southeast Asia, I actually saw only one case of this disease and the person afflicted exhibited only a slight swelling of one leg. blowfly like we might see buzzing around a road-killed opossum here in Indiana. If that was the habit of Dermatobia as well, we might rest easily in its presence. But, as you can guess, this botfly isn’t nearly as innocuous. Like other flies, this species goes through an elaborate reproductive metamorphosis in which it proceeds, stepwise, from egg to larva to pupa to adult. The larva, again as in other members of the fly Order, is a maggot. But, the human botfly maggot is of rather impressive countenance. The larva is nearly an inch in length, stout in girth, armed with ringlets of stiff, spiny bristles, and has a rather robust pair of jaws.

blowfly like we might see buzzing around a road-killed opossum here in Indiana. If that was the habit of Dermatobia as well, we might rest easily in its presence. But, as you can guess, this botfly isn’t nearly as innocuous. Like other flies, this species goes through an elaborate reproductive metamorphosis in which it proceeds, stepwise, from egg to larva to pupa to adult. The larva, again as in other members of the fly Order, is a maggot. But, the human botfly maggot is of rather impressive countenance. The larva is nearly an inch in length, stout in girth, armed with ringlets of stiff, spiny bristles, and has a rather robust pair of jaws. were to rid themselves of their grisly cargo. I could also not avoid the realization that this fly would just as opportunely infect me in the same manner. One might wonder how a fly as large as this could so furtively deposit its egg on either a howler monkey or a human. Surely it would be easy to hear its buzzing approach and shoo it away. But here again the amazing deviousness, in regards to completing a life cycle, which has evolved in parasites comes into play. The human botfly uses a less detectable emissary to deliver its egg payload, most often a mosquito.

were to rid themselves of their grisly cargo. I could also not avoid the realization that this fly would just as opportunely infect me in the same manner. One might wonder how a fly as large as this could so furtively deposit its egg on either a howler monkey or a human. Surely it would be easy to hear its buzzing approach and shoo it away. But here again the amazing deviousness, in regards to completing a life cycle, which has evolved in parasites comes into play. The human botfly uses a less detectable emissary to deliver its egg payload, most often a mosquito. This is assuming, of course, that the physician is somewhat familiar with tropical diseases and recognizes what is going on; this is not always a given.

This is assuming, of course, that the physician is somewhat familiar with tropical diseases and recognizes what is going on; this is not always a given.

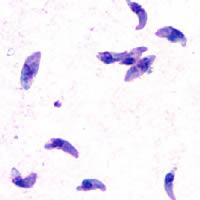

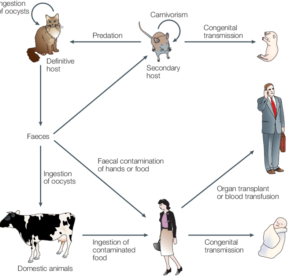

common in a variety of mammals. These include cats, rodents, pigs, and humans. By some estimates, nearly thirty percent of the world’s human population is infected with Toxoplasma. Normally the protozoan, after causing initial flu-like symptoms, resides in the human body without further affect – or so it was thought.

common in a variety of mammals. These include cats, rodents, pigs, and humans. By some estimates, nearly thirty percent of the world’s human population is infected with Toxoplasma. Normally the protozoan, after causing initial flu-like symptoms, resides in the human body without further affect – or so it was thought.

motorists he met with total indifference. Furthermore, he openly criticized the ruling Communist Party, a most dangerous endeavor at that time. Doing research in a war torn area of Turkey, he was surprised that his reaction to nearby gunfire was complete lack of distress and absence of any instinct to take cover. All of these behaviors bore an uncanny resemblance to the daredevil antics of a rat with toxoplasmosis.

motorists he met with total indifference. Furthermore, he openly criticized the ruling Communist Party, a most dangerous endeavor at that time. Doing research in a war torn area of Turkey, he was surprised that his reaction to nearby gunfire was complete lack of distress and absence of any instinct to take cover. All of these behaviors bore an uncanny resemblance to the daredevil antics of a rat with toxoplasmosis.

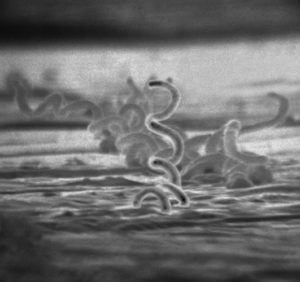

most of her coworkers, she had acquired syphilis during this time. As you know, this is a highly contagious, sexually transmitted disease caused by a bacterium named Treponema pallidum. This bacterium is a type of spirochete, so-called because of its helically spiraled shape.

most of her coworkers, she had acquired syphilis during this time. As you know, this is a highly contagious, sexually transmitted disease caused by a bacterium named Treponema pallidum. This bacterium is a type of spirochete, so-called because of its helically spiraled shape. Leucochloridium parasitizes birds. The big problem faced by Leucochloridium, and parasites in general, is how to get from one host to another. Endoparasites are highly and specifically adapted for surviving in the warm, dark, nutrient rich innards of their host. They are not built to function in what for them is the hostile outer world we humans inhabit. Here the atmosphere is highly oxygenated, there is intense sunlight, and ambient temperatures are highly variable. Yet, to continue their species, they must find a way to insinuate their adult progeny into the internal organs of another host.

Leucochloridium parasitizes birds. The big problem faced by Leucochloridium, and parasites in general, is how to get from one host to another. Endoparasites are highly and specifically adapted for surviving in the warm, dark, nutrient rich innards of their host. They are not built to function in what for them is the hostile outer world we humans inhabit. Here the atmosphere is highly oxygenated, there is intense sunlight, and ambient temperatures are highly variable. Yet, to continue their species, they must find a way to insinuate their adult progeny into the internal organs of another host. banded, animated appearance bears a remarkable resemblance to a caterpillar. Of course caterpillars are a favorite food of many bird species. And remember, these puffed-up tentacles are packed with fluke larvae very much needing to get into a bird.

banded, animated appearance bears a remarkable resemblance to a caterpillar. Of course caterpillars are a favorite food of many bird species. And remember, these puffed-up tentacles are packed with fluke larvae very much needing to get into a bird. than an inch) wasp with a beautiful metallic greenish-bluish body color. And, it does indeed parasitize cockroaches. As you might guess, it is the manner in which it does so that is dumbfounding.

than an inch) wasp with a beautiful metallic greenish-bluish body color. And, it does indeed parasitize cockroaches. As you might guess, it is the manner in which it does so that is dumbfounding. antennae with its jaws, the wasp leads its host to a previously prepared burrow in the ground. Like a well-trained dog on a lead, the cockroach obediently allows itself to be ushered, by the wasp, down into its own tomb.

antennae with its jaws, the wasp leads its host to a previously prepared burrow in the ground. Like a well-trained dog on a lead, the cockroach obediently allows itself to be ushered, by the wasp, down into its own tomb. Walking within the tropical rainforest of the Peruvian Amazon is always an adventure. One never quite knows what to expect next. It could be a hitherto un-encountered monkey species, an important medicinal plant, a spectacularly colored bird, or a Yagua hunter moving stealthily along the path blowpipe in hand. On this occasion, the encounter involved an insect and it opened a window into an often hidden aspect of tropical rainforest biology both fascinating and disturbing.

Walking within the tropical rainforest of the Peruvian Amazon is always an adventure. One never quite knows what to expect next. It could be a hitherto un-encountered monkey species, an important medicinal plant, a spectacularly colored bird, or a Yagua hunter moving stealthily along the path blowpipe in hand. On this occasion, the encounter involved an insect and it opened a window into an often hidden aspect of tropical rainforest biology both fascinating and disturbing. birds, a stunning little wire-tailed manakin – a gem of the rainforest not to mention one of its most accomplished dancers. As we continued along the trail, my eyes wandered over the surrounding vegetation. On the lookout for any movement, I also scanned for the quiet presence of eyelash viper, a species prone to lie about on low vegetation.

birds, a stunning little wire-tailed manakin – a gem of the rainforest not to mention one of its most accomplished dancers. As we continued along the trail, my eyes wandered over the surrounding vegetation. On the lookout for any movement, I also scanned for the quiet presence of eyelash viper, a species prone to lie about on low vegetation.  This habit made it a good idea to always look ahead and be aware of where one placed arms, legs, and torso. As I glanced to my left, I noticed a liana creeping from the ground and ascending at a shallow angle up into a nearby tree. Perched upon this liana was a small insect. But what a strange little insect it was. Protruding from its body was what I took to be a pair of exceedingly long antennae. But something didn’t seem quite right; the antennae seemed greatly out of proportion to the insect’s size. Stepping closer, I recognized the insect as a snout beetle. Curculionids are

This habit made it a good idea to always look ahead and be aware of where one placed arms, legs, and torso. As I glanced to my left, I noticed a liana creeping from the ground and ascending at a shallow angle up into a nearby tree. Perched upon this liana was a small insect. But what a strange little insect it was. Protruding from its body was what I took to be a pair of exceedingly long antennae. But something didn’t seem quite right; the antennae seemed greatly out of proportion to the insect’s size. Stepping closer, I recognized the insect as a snout beetle. Curculionids are

behaviors. Ants infected in such a way may not just climb to a precise height about the ground. They are also induced by the fungal parasite to clamp their jaws onto a stem or leaf petiole with great force. Thus fastened to its perch the ant, after its death, is less likely to fall back to the forest floor before the fungi’s spores are released into the air. Based upon fossil evidence, it appears that this fungus-insect relationship may have evolved several tens of millions of years ago. As this scenario played through my mind, I reflected back to a comment I once heard made by a tropical rainforest biologist. Referring to this type of fungi’s devious biochemical mind control of the host he said, “. . . and we refer to the fungi as a lower form of life?”

behaviors. Ants infected in such a way may not just climb to a precise height about the ground. They are also induced by the fungal parasite to clamp their jaws onto a stem or leaf petiole with great force. Thus fastened to its perch the ant, after its death, is less likely to fall back to the forest floor before the fungi’s spores are released into the air. Based upon fossil evidence, it appears that this fungus-insect relationship may have evolved several tens of millions of years ago. As this scenario played through my mind, I reflected back to a comment I once heard made by a tropical rainforest biologist. Referring to this type of fungi’s devious biochemical mind control of the host he said, “. . . and we refer to the fungi as a lower form of life?” Although they now reside within their own taxonomic kingdom, several generations of biologists once thought of fungi as odd members of the plant kingdom. Fungi lack the indicators of complexity we humans hold in high esteem such as mobility, a central nervous system, and some degree of intelligence. In light of this, the ability of an organism such as Cordyceps to invade an animal and take over control of its mental faculties is downright astounding – and scary. Lest you think that Cordyceps is unique in its uncanny ability to turn its host into a virtual zombie, stay tuned. The Stealth Attack Part 2 will be coming soon.

Although they now reside within their own taxonomic kingdom, several generations of biologists once thought of fungi as odd members of the plant kingdom. Fungi lack the indicators of complexity we humans hold in high esteem such as mobility, a central nervous system, and some degree of intelligence. In light of this, the ability of an organism such as Cordyceps to invade an animal and take over control of its mental faculties is downright astounding – and scary. Lest you think that Cordyceps is unique in its uncanny ability to turn its host into a virtual zombie, stay tuned. The Stealth Attack Part 2 will be coming soon.

communities in this area have descriptive names such as Prairie Creek, Prairieton, Indian Prairie, or Shaker Prairie. This morning, at various spots along my road, I am greeted by big bluestem, little bluestem, cup plant, tall goldenrod, common milkweed, Indian grass, and butterfly weed. All these represent remnants of the fingers of tallgrass prairie which probed the vacant spots along the western flanks of North America’s immense, eastern deciduous forest. It is impossible for me to consider these plants and not have my mind rush backwards as though I have exerted a forceful pull on the operative lever of H.G. Well’s time machine. I try with all my might to picture a sea of these plants, and many

communities in this area have descriptive names such as Prairie Creek, Prairieton, Indian Prairie, or Shaker Prairie. This morning, at various spots along my road, I am greeted by big bluestem, little bluestem, cup plant, tall goldenrod, common milkweed, Indian grass, and butterfly weed. All these represent remnants of the fingers of tallgrass prairie which probed the vacant spots along the western flanks of North America’s immense, eastern deciduous forest. It is impossible for me to consider these plants and not have my mind rush backwards as though I have exerted a forceful pull on the operative lever of H.G. Well’s time machine. I try with all my might to picture a sea of these plants, and many  other species of course, stretching away to the horizon. What a vista it must have been; the bluestem, tall as a man on horseback, rippling in the wind and interspersed with inestimable acres of purple coneflower, leadplant, blazing star, rattlesnake

other species of course, stretching away to the horizon. What a vista it must have been; the bluestem, tall as a man on horseback, rippling in the wind and interspersed with inestimable acres of purple coneflower, leadplant, blazing star, rattlesnake master, grama grass, cutleaf silphium, partridge pea, queen of the prairie, and rosinweed! A herd of American bison, numbering in multiples of a thousand, can be seen slowly cruising among the prairie plants and industriously converting sunlight energy into muscle, sinew, and bone. It is a grand scene that plays in my mind. Admittedly, my vision is tinged with melancholy as I recall that over ninety percent of North America’s tallgrass prairie is now gone. I am reminded of the words of the great conservationist Aldo Leopold. “What a thousand acres of Silphiums looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked.”

master, grama grass, cutleaf silphium, partridge pea, queen of the prairie, and rosinweed! A herd of American bison, numbering in multiples of a thousand, can be seen slowly cruising among the prairie plants and industriously converting sunlight energy into muscle, sinew, and bone. It is a grand scene that plays in my mind. Admittedly, my vision is tinged with melancholy as I recall that over ninety percent of North America’s tallgrass prairie is now gone. I am reminded of the words of the great conservationist Aldo Leopold. “What a thousand acres of Silphiums looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked.”

than the scoundrels mentioned above. In fact, I find them downright attractive. Queen Anne’s lace is a lovely, white-flowered native of Europe and a relative of the domestic carrot. There are also dandelions to be seen here and there. Another European native, this plant is also a common member of that diverse assemblage of flora that passes for my lawn. Many berate the dandelion for its audacity in marring their well-manicured yard. But I welcome it and sometimes take advantage of it in the spring when, upon experiencing a dearth of morels, I pick the blossoms and fry them in egg, flour, and butter. Thus prepared they are quite delicious. This morning I see chicory too; its vibrant blue flowers stand out like little neon signs along the road. Another Eurasian import, chicory has a long history of use by humans both as a food and as a coffee substitute.

than the scoundrels mentioned above. In fact, I find them downright attractive. Queen Anne’s lace is a lovely, white-flowered native of Europe and a relative of the domestic carrot. There are also dandelions to be seen here and there. Another European native, this plant is also a common member of that diverse assemblage of flora that passes for my lawn. Many berate the dandelion for its audacity in marring their well-manicured yard. But I welcome it and sometimes take advantage of it in the spring when, upon experiencing a dearth of morels, I pick the blossoms and fry them in egg, flour, and butter. Thus prepared they are quite delicious. This morning I see chicory too; its vibrant blue flowers stand out like little neon signs along the road. Another Eurasian import, chicory has a long history of use by humans both as a food and as a coffee substitute. taking advantage of the wet soil there. This plant has long intrigued me for the eclectic uses it offered generations of native peoples. The long, durable leaves could be woven into mats for floor or wall. The roots are quite edible. They remind me somewhat of cabbage. I’ve been told that cattail pollen has served as a substitute for flour in making pancakes. It is also a plant much favored for nesting by one of my favorite birds, the red-winged blackbird. Sadly, this plant has been replaced over much of its range here in Sullivan County by a non-native subspecies of Phragmites. This very tall invasive grass grows in dense stands, blocks shorelines, forms virtually impenetrable stands, and in my eyes has none of the virtues of the cattail.

taking advantage of the wet soil there. This plant has long intrigued me for the eclectic uses it offered generations of native peoples. The long, durable leaves could be woven into mats for floor or wall. The roots are quite edible. They remind me somewhat of cabbage. I’ve been told that cattail pollen has served as a substitute for flour in making pancakes. It is also a plant much favored for nesting by one of my favorite birds, the red-winged blackbird. Sadly, this plant has been replaced over much of its range here in Sullivan County by a non-native subspecies of Phragmites. This very tall invasive grass grows in dense stands, blocks shorelines, forms virtually impenetrable stands, and in my eyes has none of the virtues of the cattail. me of the labor intensive work required to collect them. One can expect badly scratched hands as a souvenir of gathering them as well. Here is a life lesson perhaps. Something as coveted as a blackberry cobbler does not come without effort.

me of the labor intensive work required to collect them. One can expect badly scratched hands as a souvenir of gathering them as well. Here is a life lesson perhaps. Something as coveted as a blackberry cobbler does not come without effort. ound the long, erect flower stems to be good substitutes for lances and yes, of course we threw them at each other. The plant having been here for over two centuries, some Native American tribes used mullein for medicinal purposes. Smoking the dried leaves was said to treat respiratory conditions such as bronchitis.

ound the long, erect flower stems to be good substitutes for lances and yes, of course we threw them at each other. The plant having been here for over two centuries, some Native American tribes used mullein for medicinal purposes. Smoking the dried leaves was said to treat respiratory conditions such as bronchitis. between boilings is recommended. Several species of birds feed on pokeweed berries and are unaffected by its poisonous components phytolaccine, phytolaccatoxin, and phytolaccigenin.

between boilings is recommended. Several species of birds feed on pokeweed berries and are unaffected by its poisonous components phytolaccine, phytolaccatoxin, and phytolaccigenin. tempted to stop and help disperse the seeds. There was a captivating beauty in seeing the small, flattened, black seeds whisked into the air by a stiff breeze. Riding the air currents, their cotton-like fluff caught the wind and parachuted the seeds to great heights and far distances. I stood mesmerized by the spectacle of these little packets of starch and DNA being launched into the waiting landscape. What was their fate I wondered? How many would fall upon fertile ground? How many would find the inhospitable world of tarmac, concrete, or water? Away from my road, these plants have been significantly displaced by farming and herbicide application. This is detrimental to the monarch butterfly whose population has undergone drastic decline in the past twenty years or so. Their larvae feed exclusively upon milkweed leaves and incorporate the plant’s toxins into their tissues. Thus they become foul tasting and poisonous to predators. I see no monarchs on today’s walk.

tempted to stop and help disperse the seeds. There was a captivating beauty in seeing the small, flattened, black seeds whisked into the air by a stiff breeze. Riding the air currents, their cotton-like fluff caught the wind and parachuted the seeds to great heights and far distances. I stood mesmerized by the spectacle of these little packets of starch and DNA being launched into the waiting landscape. What was their fate I wondered? How many would fall upon fertile ground? How many would find the inhospitable world of tarmac, concrete, or water? Away from my road, these plants have been significantly displaced by farming and herbicide application. This is detrimental to the monarch butterfly whose population has undergone drastic decline in the past twenty years or so. Their larvae feed exclusively upon milkweed leaves and incorporate the plant’s toxins into their tissues. Thus they become foul tasting and poisonous to predators. I see no monarchs on today’s walk. meat and milk of cattle which graze the plant. The result is a disease called milk sickness. This disorder was common in the 1800’s and caused the death of many people in the Midwest. When reading about this plant, the victim most famously mentioned is Abraham Lincoln’s mother Nancy Hanks Lincoln. She died from milk sickness in 1818. Eventually the connection between white snakeroot and the disease came to be understood, apparently as the result of herbal lore passed from a Shawnee woman. The flowers of the plant are attractive and my wife often uses them in fresh-cut bouquets. The fluffy, white blossoms arranged in flat-headed panicles upon the upper stems appear quite innocuous. A curious but uninformed observer would never guess the tragic history of this plant’s relationship with our pioneer ancestors.

meat and milk of cattle which graze the plant. The result is a disease called milk sickness. This disorder was common in the 1800’s and caused the death of many people in the Midwest. When reading about this plant, the victim most famously mentioned is Abraham Lincoln’s mother Nancy Hanks Lincoln. She died from milk sickness in 1818. Eventually the connection between white snakeroot and the disease came to be understood, apparently as the result of herbal lore passed from a Shawnee woman. The flowers of the plant are attractive and my wife often uses them in fresh-cut bouquets. The fluffy, white blossoms arranged in flat-headed panicles upon the upper stems appear quite innocuous. A curious but uninformed observer would never guess the tragic history of this plant’s relationship with our pioneer ancestors. used for any plant that is growing where a human doesn’t want it. Marion Jackson in his The Natural Heritage of Indiana quotes R.W. Emerson’s definition of a weed. I like this one better. “What is a weed? A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” Joe-Pye is a perfect example. Seen along the roadside from an automobile whizzing along at a mile a minute one might indeed be inclined to remark, “Look at that pretty weed.” But gardeners know better. Joe-Pye weed is virtuous as an ornamental plant. Its height and lush, umbrella-shaped, mauve flowers make it stand out as a bold addition to a garden or landscaping project. Furthermore, the very name of the plant alludes to its reputed virtues as a medicinal plant. Legend tells us that Joe Pye was the English name taken by a Native American healer who demonstrated the medicinal properties of the plant to settlers in New England. Teas made from Joe-Pye weed were said to be useful in treating everything from typhoid to rheumatism to impotence. Another name for the plant (gravel-root) was derived from its purported effect in eliminating kidney and gall bladder stones. Are there chemicals in this plant that act as genuine wonder drugs? Although many of our modern drugs are derived from plants, I know of no scientific evidence confirming the efficacy of Joe-Pye weed. Still, as I take leave of this beautiful plant, I can’t help but wonder. Could it be that the Native Americans, with their intimate connection with the natural world, knew something we have yet to fully elucidate and appreciate?

used for any plant that is growing where a human doesn’t want it. Marion Jackson in his The Natural Heritage of Indiana quotes R.W. Emerson’s definition of a weed. I like this one better. “What is a weed? A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” Joe-Pye is a perfect example. Seen along the roadside from an automobile whizzing along at a mile a minute one might indeed be inclined to remark, “Look at that pretty weed.” But gardeners know better. Joe-Pye weed is virtuous as an ornamental plant. Its height and lush, umbrella-shaped, mauve flowers make it stand out as a bold addition to a garden or landscaping project. Furthermore, the very name of the plant alludes to its reputed virtues as a medicinal plant. Legend tells us that Joe Pye was the English name taken by a Native American healer who demonstrated the medicinal properties of the plant to settlers in New England. Teas made from Joe-Pye weed were said to be useful in treating everything from typhoid to rheumatism to impotence. Another name for the plant (gravel-root) was derived from its purported effect in eliminating kidney and gall bladder stones. Are there chemicals in this plant that act as genuine wonder drugs? Although many of our modern drugs are derived from plants, I know of no scientific evidence confirming the efficacy of Joe-Pye weed. Still, as I take leave of this beautiful plant, I can’t help but wonder. Could it be that the Native Americans, with their intimate connection with the natural world, knew something we have yet to fully elucidate and appreciate?

The boat’s crew made our trip a delightful bundle of exploration, learning, and pure enjoyment. The amiable Captain Mikey delivered his instructions and bits of information with splendidly dry wit and charm. I suspect he would have a good chance of success in a second career as a standup comic. Lucas and Griffin were helpful with equipment fitting and use and hovered over us like protective parents. Snorkel guide Molly gave us an informative introduction to the biology of manta rays and the need for their protection. As I listened to her, I reflected upon the fact that virtually every charismatic animal I learn about these days seems to be under assault.

The boat’s crew made our trip a delightful bundle of exploration, learning, and pure enjoyment. The amiable Captain Mikey delivered his instructions and bits of information with splendidly dry wit and charm. I suspect he would have a good chance of success in a second career as a standup comic. Lucas and Griffin were helpful with equipment fitting and use and hovered over us like protective parents. Snorkel guide Molly gave us an informative introduction to the biology of manta rays and the need for their protection. As I listened to her, I reflected upon the fact that virtually every charismatic animal I learn about these days seems to be under assault. Although there is apparently no historical usage of these structures in traditional Chinese medicine (nor any scientific evidence of their efficacy), the belief has arisen that manta ray gills may provide relief for everything from acne to cancer. Ninety-nine percent of the gill raker trade is centered in Guanzhou, China. The conservation organization SharkSavers reports that sixty-one thousand kilograms (sixty-seven tons) of manta gill material worth US $11 000 000 has been traded there yearly. Such tonnage represents the death of some ninety-seven thousand manta (and devil) rays.

Although there is apparently no historical usage of these structures in traditional Chinese medicine (nor any scientific evidence of their efficacy), the belief has arisen that manta ray gills may provide relief for everything from acne to cancer. Ninety-nine percent of the gill raker trade is centered in Guanzhou, China. The conservation organization SharkSavers reports that sixty-one thousand kilograms (sixty-seven tons) of manta gill material worth US $11 000 000 has been traded there yearly. Such tonnage represents the death of some ninety-seven thousand manta (and devil) rays. There may be hope for the manta ray. It has been noted that sales of gill rakers in Guangzhou were 60.5 tons in 2011 and 120.5 tons in 2015 with a subsequent decline due to conservation campaigns and changes in government policies.

There may be hope for the manta ray. It has been noted that sales of gill rakers in Guangzhou were 60.5 tons in 2011 and 120.5 tons in 2015 with a subsequent decline due to conservation campaigns and changes in government policies.

The waters of the Pacific were a lovely deep blue when we began. Slowly they morphed into inky blackness as the sun at last disappeared below the far horizon. Snorkeling with the manta rays was a night mission.

The waters of the Pacific were a lovely deep blue when we began. Slowly they morphed into inky blackness as the sun at last disappeared below the far horizon. Snorkeling with the manta rays was a night mission. This enormous mouth was propelled upward by the movements of the ray’s wings (pectoral fins) which spanned over six feet. Surging upward it came toward our float; I braced for what seemed an unavoidable impact. But, at the last second, the manta performed a stunningly precise loop within inches of our faces. This maneuver revealed its brilliant white belly which was etched by distinctive black blotches. These “fingerprints” allow identification of individual rays. Downward the ray now plunged into the pillar of plankton. At the bottom another perfect loop was executed and again the ray ascended toward us like some incoming cartilaginous missile. It was quite obvious that the six hundred pound ray was exquisitely aware of its surroundings, the location of its food source, and the curious onlookers looming above it. Mantas have the largest brain to body mass ratio of any fish and studies suggest that they possess self-awareness. How could it not be totally aware of its environment? As I watched the acrobatics of the ray which was soon joined by a comrade, adjectives tumbled from my unconscious. Graceful, powerful, agile, nimble, beautiful – all most appropriate but so exceptionally inadequate in the presence of this astounding creature.