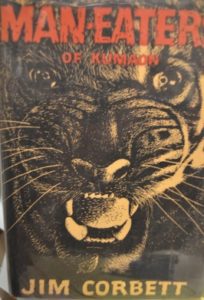

I think my fascination with tigers began when I was in high school and ran across an old book in the school library. It was written by British expatriate  James Corbett and bore the intriguing title Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Of course the topic sounded too appealingly ghastly for a teenager to pass up. In reading, I found that Corbett had been born in 1875 in India. His parents were British colonials. As an adult, he had worked for the Bengal and North Western Railway. Having taken a keen interest in natural history from an early age, Corbett became a skilled naturalist, hunter, author, and photographer. In spite of these wide-ranging accomplishments, he is today best known as a hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards.

James Corbett and bore the intriguing title Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Of course the topic sounded too appealingly ghastly for a teenager to pass up. In reading, I found that Corbett had been born in 1875 in India. His parents were British colonials. As an adult, he had worked for the Bengal and North Western Railway. Having taken a keen interest in natural history from an early age, Corbett became a skilled naturalist, hunter, author, and photographer. In spite of these wide-ranging accomplishments, he is today best known as a hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards.

Man-Eaters of Kumaon is still a highly entertaining and, at times, hair-raising tale. Two particular aspects of his tale fascinated me in. First there was the unwavering courage Corbett displayed in his solo pursuit, sometimes at night, of these exceedingly dangerous animals. The other facet of his account which intrigued me was the terrifyingly aberrant behavior of the cats themselves. These were animals which had totally lost their innate fear of humans and had, in fact, begun to actively hunt people as prey. I call their behavior aberrant because the killing and eating of humans is (thankfully) far from normal behavior for tigers (or leopards). Corbett found, as have others, that such cats nearly always began selecting humans as prey because they had a physical impediment of some sort. Canine teeth worn or broken from usage and age, a face or paw full of porcupine quills which had become infected, a weakened forelimb caused by a poacher’s poorly-aimed bullet . All of these could cause a tiger to pursue the weaker, defenseless quarry represented by humans.

As a biology graduate student at Illinois State U., I once had the chance to examine a tiger very closely. Captive animals, which had died at the local zoo, would often be donated to our biology department. Here we would remove the skin for preservation and prepare the skull and post-axial skeleton for addition to the vertebrate collections. Although I had seen many tigers in zoos, I had never fully appreciated their size until I began work on this specimen. The forepaws of the great cat were literally the size of large dinner plates. Claws nearly four inches long could be extended from each massive forefoot. These could easily impale and grasp a deer or produce a slash as deeply and neatly as a butcher’s knife. The legs were impressively muscular with their underlying flexors and extensors developed to prodigious size and tone. It was exceedingly easy to see how one swipe from an immense paw could crush the skull of a sambar deer – or a human. Within the upper jaw resided canine teeth which extended nearly three inches in length from the gum line. Powered by immense masseter muscles, such teeth were capable of piercing the skull or spine of a prey animal as effortlessly as we might bite into a sandwich. The tiger measured almost four feet tall at the shoulders. From nose to tail-tip it stretched some eight and a half feet and weighed in at nearly three hundred pounds. Imagine a cat so big it could rear up and put its forepaws on the bottom of a basketball backboard! All in all, this tiger specimen was physically huge and frighteningly imposing. The mere thought of being silently, stealthily stalked by such an animal was terrifying.

One specific story that Corbett related in his Man-Eaters of Kumaon, perhaps the most disturbing, gives a perspective on the physical mismatch between a tiger and its human prey. It also sheds light on how a man-eater could  impose sheer terror upon the human population of an entire district. In the year 1907, Corbett was called upon to dispatch a man-eater which had come to be called the Champawat Tiger. Champawat was a village, in the Indian district of Kumaon. The cat had moved into this area after previously roaming in adjacent Nepal. Upon arriving in this village, Corbett heard a chilling eyewitness account of the tiger’s predations. A party of men who had been walking a rural road to Champawat had this story to tell: “We were startled by hearing the agonized cries of a human being coming from the valley below. . . we cowered in fright as these cries drew nearer and nearer, . . . presently into view came a tiger, carrying a naked woman. The woman’s hair was trailing on the ground on one side of the tiger, and her feet on the other.” The tiger quickly crossed the road and disappeared into the bush carrying the screaming, flailing women as a house cat would carry a mouse. Her pitifully scant remains – a few bones, the remnant of a sari – were found the next day. A more horrifying end of life is difficult to imagine. Before Corbett ended its reign of terror, the Champawat Tiger is believed to have killed over 400 people. The gruesomeness of this narrative still sends shivers down my spine. After having this nightmarish story emblazoned upon my teenage memory is it any wonder that, even years later, my first camp-out in the tiger-inhabited jungle of the Malay Peninsula left me shall I say – uneasy?

impose sheer terror upon the human population of an entire district. In the year 1907, Corbett was called upon to dispatch a man-eater which had come to be called the Champawat Tiger. Champawat was a village, in the Indian district of Kumaon. The cat had moved into this area after previously roaming in adjacent Nepal. Upon arriving in this village, Corbett heard a chilling eyewitness account of the tiger’s predations. A party of men who had been walking a rural road to Champawat had this story to tell: “We were startled by hearing the agonized cries of a human being coming from the valley below. . . we cowered in fright as these cries drew nearer and nearer, . . . presently into view came a tiger, carrying a naked woman. The woman’s hair was trailing on the ground on one side of the tiger, and her feet on the other.” The tiger quickly crossed the road and disappeared into the bush carrying the screaming, flailing women as a house cat would carry a mouse. Her pitifully scant remains – a few bones, the remnant of a sari – were found the next day. A more horrifying end of life is difficult to imagine. Before Corbett ended its reign of terror, the Champawat Tiger is believed to have killed over 400 people. The gruesomeness of this narrative still sends shivers down my spine. After having this nightmarish story emblazoned upon my teenage memory is it any wonder that, even years later, my first camp-out in the tiger-inhabited jungle of the Malay Peninsula left me shall I say – uneasy?

Although decades have passed, it still seems only yesterday that my friends  Dodong, Oha, and I had completed our day’s trek and prepared our camp for the night. Although far from a neophyte when it came to woodcraft, I found the skill the two Temuan tribesmen exhibited in forging a campsite from the materials at hand to be impressively efficient and rapid. Using thin vines as lashings, Dodong and Oha fixed a cross-piece between two sapling trees. They then cut several atap palm leaves about ten feet in length. The butt ends of these were

Dodong, Oha, and I had completed our day’s trek and prepared our camp for the night. Although far from a neophyte when it came to woodcraft, I found the skill the two Temuan tribesmen exhibited in forging a campsite from the materials at hand to be impressively efficient and rapid. Using thin vines as lashings, Dodong and Oha fixed a cross-piece between two sapling trees. They then cut several atap palm leaves about ten feet in length. The butt ends of these were  placed in the ground and the leaves leaned forward to rest upon, and droop over, the cross-piece. Thus we had a small lean-to in which to shelter for the night. There was no floor of course; we simply flopped down on the ground to sleep.

placed in the ground and the leaves leaned forward to rest upon, and droop over, the cross-piece. Thus we had a small lean-to in which to shelter for the night. There was no floor of course; we simply flopped down on the ground to sleep.

Dodong urged a fire from wood that appeared to my eyes so impossibly damp one could have wrung water from it. But nevertheless, a substantial cooking fire was soon producing heat. On this pleasantly cozy blaze we roasted some diminutive catfish we had caught from a nearby stream. We also steamed rice, the one necessity needed to make any Asian meal complete. After we had eaten, we lounged around the fire and my friends set about restocking a supply of darts for their blowpipes. These they fashioned from atap palm stems whittled to a fine point. They were tipped with poison extracted by boiling the bark of a tree that they called ipoh (Antiaris toxicaria). The toxin gave the darts, after drying by the fire, the appearance of having been tipped with black paint. The projectiles were used in pursuit of birds, squirrels, and monkeys; all staples of the Temuan diet. The sap of the ipoh tree contains organic compounds known as cardiac glycosides. These chemicals are used in modern medicine to treat heart disease but, like many drugs, can be toxic if too much is given. A 1953 paper in the British Journal of Pharmacology found that test animals exposed to the ipoh tree toxin had their blood pressure rapidly fall to zero. “When the heart was examined after death the left ventricle was found to be tightly contracted and hard (Blowpipe Dart Poison from Borneo by Robinson and Ling).” Dodong put it more succinctly when he related that a monkey struck by one of their darts died within about the same amount of time it took him to smoke a cigarette. I also noted that he studiously avoided letting me handle darts that had been tipped in “ipoh”. Apparently an orang puteh simply could not be trusted to avoid accidentally stabbing himself.

As Dodong and Oha chatted (in Malay for my benefit) and worked on their armaments, my mind began to contemplate sleeping directly upon the ground that night. Naturally, a list of unwelcome guests which might invite themselves for a visit began to scroll through my mind. First there were the arthropods to consider. I had already, during one of my night-time forays into the rainforest, encountered the huge tropical centipede, Scolopendra. A friend who had been envenomed by the fangs of one of these critters told me that, for several days, it felt like he had had his hand slammed in a car door. I did not relish accidentally rolling over onto one of these. A rather frightening relative of the centipede was the enormous, black forest scorpion that patrolled the ground here. Although its sting was said to be less potent than that of Scolopendra, it was an assertion I did not care to test.

Of course there was a variety of venomous snakes to consider. Since arriving in Malaysia, I had found the Indian cobra to be extremely common. Its big cousin the king cobra also prowled these forests. Known to reach a record length of over eighteen feet, a snake this size would pack enough venom to kill a human in a matter of minutes. Certainly not an animal I wanted to be looking in the eyes should I awaken in the middle of the night. There were  kraits, coral snakes and pit-vipers here too. I couldn’t help but recall an old western I’d seen as a youngster in which a rattlesnake, seeking warmth, had crawled into a cowpokes’ sleeping bag and decided to take a lingering rest upon the man’s stomach. Still, reviewing the list of possible nocturnal companions was not a cause for anxiety. No phobias revealed themselves. The various creatures I contemplated were just that, simply considerations, possibilities with which one might have to deal.

kraits, coral snakes and pit-vipers here too. I couldn’t help but recall an old western I’d seen as a youngster in which a rattlesnake, seeking warmth, had crawled into a cowpokes’ sleeping bag and decided to take a lingering rest upon the man’s stomach. Still, reviewing the list of possible nocturnal companions was not a cause for anxiety. No phobias revealed themselves. The various creatures I contemplated were just that, simply considerations, possibilities with which one might have to deal.

Now nightfall descended, as it does near the equator, with what seemed the suddenness of flipping off a light switch. The cacophony of frogs, toads, and insects began and I sat enthralled by the position in which I found myself. I was gripped by a feeling of absolute bliss. Abruptly there also came an epiphany, a realization of the fortunate destiny of my position. Here sat George Sly from small-town USA, an average guy and even more average student. I now rested on the opposite side of the globe, twelve-thousand miles from my Indiana home. I was sitting in the heart of a stunningly rich, intact tropical rainforest 100 million years in the making. With me were two of the few remaining people on earth still capable of not just surviving but thriving in a manner totally independent of modern society. How was it that I had been granted such an extraordinary opportunity I pondered? I still do not know. The twists and turns of one’s experiences, the choices and contingencies that result in the final trajectory of a life remain mysterious to me. I do know that this night left a significant mark in my psyche. Never again would I enter the natural world, or engage with another culture, and remain oblivious to the wonderful good fortune and the opportunities for adventure and understanding which have been bestowed upon me.

I was jerked back to awareness by the sudden exclamation of a muntjac (barking deer). Its sharp, fox-like call hung upon the night air. Recalling that this species was a primary prey in the diet of tigers, I asked Dodong if we might encounter the big cat. Yes, there were tigers in this area he said. There were also leopards and clouded leopards. We might hear a tiger he thought but seeing one was not so likely. My mind flashed to a recent report in the Straits Times of a tiger in northern Pahang state which had boldly entered an aborigine man’s hut and carried him away.

Still, my Temuan friends didn’t seem overly concerned about camping in tiger country. In fact, as we talked, they seemed much more ill at ease in regards to the possibility of encountering a tiger-mimicking creature they called the hantu harimau. Dodong described how this forest-inhabiting spirit could assume the form of various animals. To the observer, it might first appear as a bird and then, fluttering closer, a squirrel. These ruses were used, as it hopped from tree to tree, to sneakily move ever nearer to a person. When the hantu had thus come very close, it would suddenly take the form of a tiger. With a great roar the tiger would then launch itself upon its helpless human victim. Here was a tale! Told while surrounded by the impenetrable darkness and resonances of the forest, it was guaranteed to raise one’s hackles and make easy sleep a nonstarter.

I would like to be able to report that during the night I heard the greeting chuff or the territorial moaning of a tiger. It would please me even more to tell of the brief, unnerving glimpse I had as the cat melted away into the surrounding darkness. Alas, after three years in Malaysia and countless trips into its rainforests, I was never bestowed the gift of seeing a wild tiger. Perhaps the forest of my Temuan friends was not primeval enough. But sallies into the more pristine rainforest of Taman Negara, Malaysia’s major national park, were no more productive. Even seeing the spoor of Panthera tigris eluded me. And yet, in spite of this, the mere knowledge that one walked in tiger country was sufficient to endow the experience with a mystique that was tangible. One does not walk there without thinking of tiger. There is the periodic, involuntary, self-protective glance over the shoulder, the startle at the sudden snap of a twig or the flushing of a pheasant, a pause to consider why the forest has suddenly gone silent.

“The land retains an identity of its own, still deeper and more subtle than we can know. Our obligation toward it then becomes simple . . . To try to sense the range and variety of its expression . . . To intend from the beginning to preserve some of the mystery within it as a kind of wisdom to be experienced.”

Barry Lopez in Arctic Dreams

The great American conservationist Aldo Leopold once wrote of a grizzly bear that inhabited a mountain called Escudilla in Arizona. Upon seeing the mountain against the Arizona sky, one was automatically reminded of the legendary grizzly which roamed its heights. The mountain was permeated with his presence. The big bear was the sole  survivor of his kind on the mountain. But the country must be made safe for cattle; a government trapper was dispatched. The big bear was taken. Leopold lamented that from this time forth, when one gazed upon the immense hulk of Escudilla hanging on the far horizon, one no longer thought of the big grizzly. Escudilla was just another mountain now.

survivor of his kind on the mountain. But the country must be made safe for cattle; a government trapper was dispatched. The big bear was taken. Leopold lamented that from this time forth, when one gazed upon the immense hulk of Escudilla hanging on the far horizon, one no longer thought of the big grizzly. Escudilla was just another mountain now.

And so it is with the rainforest and its tiger, the Pantanal and its jaguar, Yellowstone and its wolf. Without these magnificent keystone species, such places are just a collection of trees, only a marshy vastness, merely a coniferous forest. I do not need to see a tiger in order to delight in simply knowing that such an animal exists. Even though we may never visit these places, or see these animals, it is enough to know that they are still present. Why? Because such lands, such species allow us to imagine, to dream, to acknowledge our ancestral connections with the natural world. The presence of wildness in land or beast comforts us with the awareness, even if subliminal, that our earth is still well.

In the final analysis, even those who proclaim disinterest in the natural world must surely recognize that we have a moral obligation to our grandchildren, great grandchildren, and generations beyond. They should inherit a certain entitlement. Such a birthright would allow them the opportunity to successfully seek out wild places and wild things themselves. Without untamed places and the ferine beings that inhabit them, it will certainly be an impoverished world, a less remarkable world we bequeath our descendants.