Like many people who love things wild, I’ve always been intrigued by the large predatory cats. Lions, tigers, and mountain lions in particular have captivated me. Their physical strength, grace, and ability to maneuver noiselessly within their world have always struck me as paragons of predatory evolution. As a youngster, I dreamed that one day I might be able to actually see one of these magnificent cats in the wild. Of course actually doing so would be a significant challenge. Tigers and mountain lions are solitary and unbelievably stealthy in their movements. They also have an aversion to exposing themselves to their arch enemy – humans. Lions are social and more easily observed but, like their relatives, they lived at great distances from my Indiana home. In spite of these obstacles, I remained hopeful and – sometimes dreams do come true.

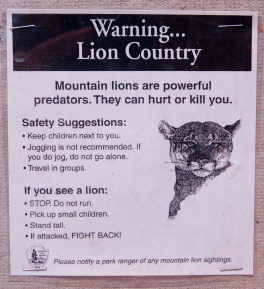

The mountain lion has many pseudonyms. Puma (from the Quechua word  for them), panther, and cougar are the more commonly used. This species has a large geographic range and occurs not only in the United States but down through Mexico, Central America, and into much of South America. I had always assumed that, should I be lucky enough to see a mountain lion, it would be in the western United States. As it turned out, it was the tropical rainforest of Peru that provided this rare and thrilling opportunity.

for them), panther, and cougar are the more commonly used. This species has a large geographic range and occurs not only in the United States but down through Mexico, Central America, and into much of South America. I had always assumed that, should I be lucky enough to see a mountain lion, it would be in the western United States. As it turned out, it was the tropical rainforest of Peru that provided this rare and thrilling opportunity.

As I, along with my guide Luis, walked through the lowland rainforest of Peru that morning, the farthest thing from my mind was a chance meeting with a mountain lion. Part of this was the fact that, as I have suggested, my mind was pre-programmed to expect this cat in a far different geographic locality. Besides, there were just so many other things to see and think about. As we sauntered along, Luis pointed out various plants of ethnobotanical interest. The use of plants for medicinal and utilitarian purposes was a field in which I had recently become interested. It seemed that Luis could elaborate upon some use for nearly every plant we encountered. There was the sap of Ficus to be used in ridding one of intestinal round worms; a most useful property in an area where worm infection was nearly universal. For a sore throat, a common ginger  produced a juice useful for gargling. The walking palm provided stout poles for building construction. The irapay palm was used throughout the region for weaving into roofing units called crisnejas. The berries of camu camu were edible and contained many times the vitamin C of a typical citrus fruit. A tree called sangre de grado produced a blood-like sap which functioned as a highly efficacious wound

produced a juice useful for gargling. The walking palm provided stout poles for building construction. The irapay palm was used throughout the region for weaving into roofing units called crisnejas. The berries of camu camu were edible and contained many times the vitamin C of a typical citrus fruit. A tree called sangre de grado produced a blood-like sap which functioned as a highly efficacious wound  healer. With a third of the modern worlds’ medicines derived from plants, I pondered what potential miracle cures might reside within the thousands of species of rainforest plants around me. Only a tiny percentage of these plants have been studied for their pharmaceutical properties. I wondered if we are unknowingly tossing away a cure for cancers, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease as we rabidly pursue our destruction of the tropical rainforests.

healer. With a third of the modern worlds’ medicines derived from plants, I pondered what potential miracle cures might reside within the thousands of species of rainforest plants around me. Only a tiny percentage of these plants have been studied for their pharmaceutical properties. I wondered if we are unknowingly tossing away a cure for cancers, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease as we rabidly pursue our destruction of the tropical rainforests.

In addition to the wondrous plant world around us, there was also the usual opportunity to experience a menagerie of bird and insect species. The background noise of the forest included the seemingly ever-present screaming piha. The piercing call of this rather nondescript bird could serve  as a background sound in any movie about the “jungle”. Occasionally we would see, or hear, mealy parrots or cobalt-winged parakeets zooming overhead. In their hurried flight, they seemed to be rushing to some important parrot convention and were running late. Manakins, jacamars, trogons, and motmots; the list of exotic avian encounters seemed endless.

as a background sound in any movie about the “jungle”. Occasionally we would see, or hear, mealy parrots or cobalt-winged parakeets zooming overhead. In their hurried flight, they seemed to be rushing to some important parrot convention and were running late. Manakins, jacamars, trogons, and motmots; the list of exotic avian encounters seemed endless.

Tropical rainforest insects are notoriously diverse and plentiful. We saw army ants on the march and termite columns that stretched away in either direction for many meters. The marching hordes of the termites reminded me of a traffic helicopter’s view of heavy traffic on the 504 in Los Angeles. Each worker returning to the nest carried a tiny chunk of wood in its diminutive jaws. Outgoing workers plodded doggedly onward toward their goal of a fallen limb or trunk.

Frequently a gorgeous blue morpho butterfly would pass near us, its cobalt-colored wings flashing in magnificence. Highly colored heliconid butterflies wafted along with their slow, inelegant flight. One would think that their bright colors and slow flight would make them an easy target for insectivorous birds. Not so; these colors warned predators of the presence of toxins in their tissues which render them unpalatable.

Scanning the ground often yielded a sighting of a pink-footed tarantula or giant millipede. Luis and I were always careful about laying our hands on trees for support without carefully glancing over them first. The boles of  trees are often patrolled by predaceous bullet ants (Paraponera). At over an inch in length, these are among the largest ants in the world. Perhaps their common name will give you an idea of the power of their sting. I can tell you from experience that inattentively placing one’s hand upon one of them is not recommended.

trees are often patrolled by predaceous bullet ants (Paraponera). At over an inch in length, these are among the largest ants in the world. Perhaps their common name will give you an idea of the power of their sting. I can tell you from experience that inattentively placing one’s hand upon one of them is not recommended.

During the days that I spent hiking with Luis, we would periodically see primates. Squirrel monkeys and saddle-backed tamarins seemed to be the most common species. Although the Peruvian rainforest is home to hundreds of species of mammals, most are either nocturnal, arboreal, or both. Thus one cannot hope to go “mammal watching” in the same way that one can successfully go birding. As a result, my mind was engaged far  from the mammalian world as we strolled along. The sudden alarm bark of an agouti jerked me back to consideration of the furred world. An agouti is a hefty rodent about the size of a cat and resembling a huge, tailless rat. There are several species of agoutis in the New World tropics. Luis said that the one calling now was a black agouti. Its alarm reminded me of the bark of a fox squirrel back in Indiana. However this warning bark gave a hint of the larger size and power of the agouti; like a fox squirrel on steroids perhaps. The rodent was calling from quite closely and I assumed it had spotted us and was voicing its unease. I searched unsuccessfully for it in the vegetation near us. So occupied, I was totally unprepared as my gaze wondered back to the trail ahead of us.

from the mammalian world as we strolled along. The sudden alarm bark of an agouti jerked me back to consideration of the furred world. An agouti is a hefty rodent about the size of a cat and resembling a huge, tailless rat. There are several species of agoutis in the New World tropics. Luis said that the one calling now was a black agouti. Its alarm reminded me of the bark of a fox squirrel back in Indiana. However this warning bark gave a hint of the larger size and power of the agouti; like a fox squirrel on steroids perhaps. The rodent was calling from quite closely and I assumed it had spotted us and was voicing its unease. I searched unsuccessfully for it in the vegetation near us. So occupied, I was totally unprepared as my gaze wondered back to the trail ahead of us.

For there, suddenly emerging onto the trail from the herbaceous growth alongside it, came a large brown animal; a very large brown animal. It materialized upon the trail as one might imagine an apparition suddenly entering the room through a wall. As the beast turned, barely twenty yards from us, and began to walk down the trail away from us my mind raced. For some reason I simply could not grasp what I was seeing. It was though a series of mammal photos on flip-cards were rapidly flashing through my memory banks. Whatever it was, this is what had caused the agouti to begin broadcasting its alarm.

As I watched the animal move away, my mind finally fixated on the odd stiff-legged gait of the hindquarters. CAT! – my subconscious suddenly shouted to me. No sooner had I made this recognition than the puma became aware of our presence. It did not run but its’ pace slightly increased. Veering off the trail, the big cat moved to put itself behind a large tree. Luis motioned wildly and shouted, “come, come, come” as he ran ahead. Following, I sped to the point in the trail where the mountain lion had disappeared. Looking out into the surrounding forest, there was nothing. Shaking with excitement I asked Luis, was that a mountain lion? “Yes, yes; tigre,” he said. It was one of the most remarkable things I had ever seen. How the animal was unaware enough to actually walk onto the trail ahead of us I can’t imagine. But, once it realized its error, the craftiness of its escape astonished me. It was as though we had encountered a spirit animal. It was not there. Then suddenly it was there. And just as abruptly, it was gone. My dream had been fulfilled and in a manner which fully enlightened me as to the adept stealthiness, the absolute noiselessness, the ghost-like movements of this enigmatic big cat.

Of course, back at the lodge, the news of our sighting was received with tremendous excitement. One simply does not go hiking in the rainforest and stumble upon a mountain lion. And yet, that had been our good fortune. Luis, who had spent his life walking rainforest trails, remarked that this was only his second encounter with a puma. As a boy, he and his father had been hunting in the forest and had just bagged a monkey. As they moved to retrieve it, a mountain lion suddenly appeared. Laying back its ears and growling furiously the cat darted in, snatched their game, and ran off into the forest. Luis and his father could only stand and stare in open-mouthed shock as their evening meal disappeared.

stumble upon a mountain lion. And yet, that had been our good fortune. Luis, who had spent his life walking rainforest trails, remarked that this was only his second encounter with a puma. As a boy, he and his father had been hunting in the forest and had just bagged a monkey. As they moved to retrieve it, a mountain lion suddenly appeared. Laying back its ears and growling furiously the cat darted in, snatched their game, and ran off into the forest. Luis and his father could only stand and stare in open-mouthed shock as their evening meal disappeared.

There is an intriguing epilogue to the story of our encounter. The day after our exceptional sighting, Luis and I were once again out walking one the trails near where our chance meeting had occurred. It was much the same routine. We scanned for birds and insects and discussed the various plants that we were seeing. At one point, we came to a cleared area in the forest. The swath was about five yards wide and extended north and south into the distant forest. I asked Luis why this path had been cleared and he explained that it marked the boundary of the forest reserve in which we now walked. Luis pointed northeast and indicated the direction of Venezuela. He then informed me that we could walk all the way there and never encounter a major village or road. This represented several hundred miles of unbroken rainforest. As I looked around and contemplated how uniform the forest looked in every direction, a chill ran down my spine. The ease with which one could become lost here, and the dire consequences should this happen, combined to impress upon me an exceedingly healthy respect for this place. It also made me highly appreciative of Luis’ companionship and his skill as a guide.

We continued our walk and after an hour or so decided, in unspoken agreement, to break for a brief rest. No sooner had we stopped than there came muffled, but quite distinct and very audibly, a low throaty growl. It was the snarl of a large cat. Luis and I quickly scanned the surrounding forest but of course we saw nothing. We were left to look at each other with simultaneous smiles of uneasy understanding. I remain firmly convinced that this cat was following us, paralleling our course, and curiously observing us. It had perceived our stopping and scanning around us as having been detected. With a twinge of annoyance, the cat had voiced its displeasure. Whether this was the mountain lion we had seen just the day before, a different one altogether, or their bigger cousin a jaguar we could not know. Suffice to say, this encounter was an unambiguous reminder that a walk in the tropical rainforest is not a stroll through Disney’s Animal World.

Still, I would not go so far as to suggest that visiting a tropical rainforest involves great danger. But I do propose that such visits often require a  mindfulness that we seldom need to practice in modern society. Most of us live in a world devoid of natural dangers. Many would argue that this is a good thing I suppose. But it seems to me that it has made our developed world a much less stimulating place in which to dwell. Henry David Thoreau said that, . . . we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be infinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed. . . . We need to witness our own limits transgressed . . .”

mindfulness that we seldom need to practice in modern society. Most of us live in a world devoid of natural dangers. Many would argue that this is a good thing I suppose. But it seems to me that it has made our developed world a much less stimulating place in which to dwell. Henry David Thoreau said that, . . . we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be infinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed. . . . We need to witness our own limits transgressed . . .”

In such manner, I need to know that there are pumas and tigers roaming the forests of the world. A hike in Yellowstone country must entail the chance of meeting a grizzly bear or hearing the nearby howl of a wolf. Large predatory mammals prompt us to recall our own wild, ancestral heritage. They remind us that once “we” all possessed critical survival skills. Apex predators encourage us to recall that our earth is home to a wondrous richness of species. As humans, we need to know that the opportunity to hear the guttural growl of a big cat skulking close at hand still exists. When such an extraordinary possibility has been lost our earth will be a duller, a poorer, a decidedly less remarkable place to call home.

Photo Credits

Mountain lion Lee Elvin at Wikimedia Commons

Range map Felidae Conservation Fund (@ felidaefund.org)

Sangre de drago sap courtesy of Penbani Inversiones (perbani.com.pe)

Black agouti Al Merkins at Wikimedia Commons

All other photos by the author.