There is no quiet place in the white man’s cities, no place to hear the leaves of spring or the rustle of insects’ wings. Perhaps it is because I am a savage and do not understand, but the clatter only seems to insult the ears.

Chief Seattle

The more we exile ourselves from nature, the more we crave its miracle waters.

Diane Ackerman

These are turbulent times in which we live. A pandemic disease has many of us fearful of visiting even close friends and relatives. Our federal government appears to be in a state of dysfunction more often than not. Right, left, and in-between seem to constantly be at one another’s throats. Conspiracy theories often carry more weight than verifiable data. It is all downright discouraging.

But there is a panacea. I am fortunate; all I must do to receive this remedy is step outside. Admittedly this therapy may not be permanent. But it can be at least a temporary escape from all that is folly and this treatment can be taken over and over again. There are no undesirable side effects. I am speaking of the little dramas and comforting sounds provided by the natural world. They are reminders that my worries, stressors, and fears are but interludes in the larger symphony. Playing unabated and undiminished in the background, this opus offers us a chance to pull away from our anxieties and re-center ourselves.

As I write, it is now July. Likely I could be put into a time machine, shuffled forward and backward a few times and, when I emerged, still recognize late summer in Indiana. Common tree katydids, dusk-singing cicadas, snowy tree crickets, and other orthopterans provide a daily chorus of communicative racket. They remind me that the imperative to establish territory, find a mate, and persevere as a species beyond the cold winter to come is a powerful drive among the small, six-legged critters of the world too. I dare say the urge is every bit as potent as it is among head-butting bison or antler-entangled deer.

As I write, it is now July. Likely I could be put into a time machine, shuffled forward and backward a few times and, when I emerged, still recognize late summer in Indiana. Common tree katydids, dusk-singing cicadas, snowy tree crickets, and other orthopterans provide a daily chorus of communicative racket. They remind me that the imperative to establish territory, find a mate, and persevere as a species beyond the cold winter to come is a powerful drive among the small, six-legged critters of the world too. I dare say the urge is every bit as potent as it is among head-butting bison or antler-entangled deer.

Admittedly, I once reacted with dread to the onset of the clicking, buzzing, and vibratory rasping of these summer insects. As a teacher it reminded me that my hiatus from ten hour days and high stress levels would soon cease. I loved my profession but who doesn’t relish having time to simply do as one pleases? Happily, I now find the multitudinous chorus performing outside my door to be not only entertaining but quite beautiful (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_wua2tULh84).

August will be here soon. The insect choirs will continue for a while of course. The evenings will offer the exquisite sound of wood thrushes calling from the forest just beyond my lawn (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-22ZuQyAJ4). The hot, still days will be punctuated by the hollow-wooden cowlp, cowlp, cowlp, cowlp calls of a yellow-billed cuckoo. Likely the author of these sounds will be well-hidden and skulking about in the patch of woods to the west of the house. (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Yellow-billed_Cuckoo/sounds). Other August sounds bring me memories of childhood. The plaintive trill of a field sparrow bouncing to its conclusion carries me back to the hot days of summer when I roamed the oldfields around home in search of adventure (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Field_Sparrow/sounds).

course. The evenings will offer the exquisite sound of wood thrushes calling from the forest just beyond my lawn (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-22ZuQyAJ4). The hot, still days will be punctuated by the hollow-wooden cowlp, cowlp, cowlp, cowlp calls of a yellow-billed cuckoo. Likely the author of these sounds will be well-hidden and skulking about in the patch of woods to the west of the house. (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Yellow-billed_Cuckoo/sounds). Other August sounds bring me memories of childhood. The plaintive trill of a field sparrow bouncing to its conclusion carries me back to the hot days of summer when I roamed the oldfields around home in search of adventure (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Field_Sparrow/sounds).

September is a lovely month. There are finally some equable evenings and more moderate days to enjoy. But plunked down here in southwestern  Indiana, I cannot prevent my mind from wandering westward. The foothills of Rocky Mountain National Park or the lodgepole pine forests of Yellowstone exert a pull that is tangible. For I know it is in such places that the bull elk are into their rut. I had long wanted to hear their fantastical bugling for myself. As soon as I found myself free in this month, I went in search. What a strange, far-carrying, high-pitched sound I found issuing from such a large animal (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYzWmKlZtrU). Nowadays, I can listen to a recording of the bugling of an elk and find myself transported to another land. The smell of pine upon the air, the solitude of wilderness, the chill of a clear mountain morning, the distant clack of opposing antlers sounding from somewhere within the forested slope up above – all these reside within the bull’s weirdly wonderful bellow.

Indiana, I cannot prevent my mind from wandering westward. The foothills of Rocky Mountain National Park or the lodgepole pine forests of Yellowstone exert a pull that is tangible. For I know it is in such places that the bull elk are into their rut. I had long wanted to hear their fantastical bugling for myself. As soon as I found myself free in this month, I went in search. What a strange, far-carrying, high-pitched sound I found issuing from such a large animal (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYzWmKlZtrU). Nowadays, I can listen to a recording of the bugling of an elk and find myself transported to another land. The smell of pine upon the air, the solitude of wilderness, the chill of a clear mountain morning, the distant clack of opposing antlers sounding from somewhere within the forested slope up above – all these reside within the bull’s weirdly wonderful bellow.

October brings its own enchantments. Now the nights are not just cool but may bring the chance for frost. Migrations are well under way for most bird species and for the next couple of months a rich smorgasbord of avian sounds may be encountered. I now have the good fortune to live less than ten miles from a 9000 acre wetland restoration known as Goose Pond Fish & Wildlife Area. Following its establishment in 2005, wetland and grassland birds of many species followed the now familiar axiom of “build it and they will come.”

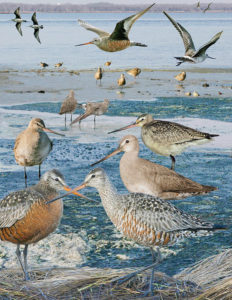

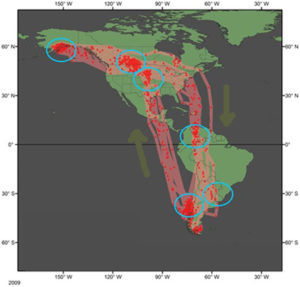

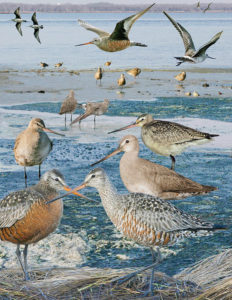

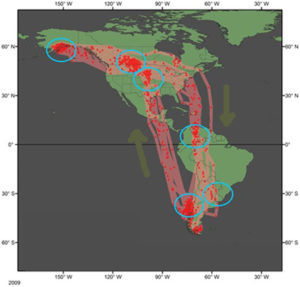

A visit to this area in late summer or early fall allows one to be serenaded with the vocalizations of waterfowl and shorebirds by the thousands. They use the property to rest and fuel up for the journeys ahead. Some may go no further than the southern U.S. but others are in the midst of migratory journeys of epic proportions. I was astounded when I first learned that among the sojourners was a bird known as the Hudsonian godwit. (www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Hudsonian_Godwit/sounds) Why? It is simply this; few other birds embark on flights as monumental as does this nine ounce avian marvel. The godwits at Goose Pond are thought to be arriving from eastern Alaska or northwestern Canada. Are they making the flight to SW Indiana nonstop? I do not know for sure. It is known that they are quite capable of such feats. Hudsonian godwits have been tracked making an uninterrupted, five day flight of some 3900 miles from Hudson Bay, Canada to the Orinoco River basin of Venezuela. Their eventual

A visit to this area in late summer or early fall allows one to be serenaded with the vocalizations of waterfowl and shorebirds by the thousands. They use the property to rest and fuel up for the journeys ahead. Some may go no further than the southern U.S. but others are in the midst of migratory journeys of epic proportions. I was astounded when I first learned that among the sojourners was a bird known as the Hudsonian godwit. (www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Hudsonian_Godwit/sounds) Why? It is simply this; few other birds embark on flights as monumental as does this nine ounce avian marvel. The godwits at Goose Pond are thought to be arriving from eastern Alaska or northwestern Canada. Are they making the flight to SW Indiana nonstop? I do not know for sure. It is known that they are quite capable of such feats. Hudsonian godwits have been tracked making an uninterrupted, five day flight of some 3900 miles from Hudson Bay, Canada to the Orinoco River basin of Venezuela. Their eventual  destination is southern Chile, some ten thousand miles from their breeding grounds. Is this the destination of our Goose Pond godwits? Quite likely it is. And the mere thought of such a feat of physical endurance and navigational shrewdness leaves me flabbergasted.

destination is southern Chile, some ten thousand miles from their breeding grounds. Is this the destination of our Goose Pond godwits? Quite likely it is. And the mere thought of such a feat of physical endurance and navigational shrewdness leaves me flabbergasted.

November can be a bit of a downer here in Indiana. Gray, dull skies, yielding days without sunshine and cold rains are recollections that come to my mind. But there is an entertaining trade-off; the lingering waterfowl provide a near-daily concert meant to lighten my mood. The flocks of geese, which nightly roost in the wetland to the east, make daily passages over my house. They are heading to, and from, the waste grain bonanza lying in the harvested fields of the Wabash River bottoms to the west.

Canada geese are commonly seen. Years ago, when I was a youngster, our family would take excited note of these birds as they passed overhead. In the fall, flocks heading southward served notice that the warm, pleasant days of summer were soon to be replaced by cold, blustery winds. In March, the sound of Canada geese forging northward in ‘V’ after ‘V’ caused us to bolt from the house and take a look skyward. Harbingers of spring they were, welcome messengers announcing that a break from cold, sleet, and snow was nearly upon us.

These days hardly anyone takes special notice of Canada geese unless to complain that they are fouling lawns or fairways. Many of them no longer migrate but remain here in the Midwest year round. Mild winters, the aforementioned agricultural fields, and an abundance of lakes which seldom freeze over for long mean their long annual trips are no longer necessary.

Recently some other players have joined the cast providing the daily  entertainment proffered me by the goose clan. The formations passing over my house are now more frequently comprised of greater white-fronted geese. Their high pitched, yelping calls allow me to hear them approaching from a distance and bear little resemblance to the deep honks of their Canadian cousins (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Greater_White-fronted_Goose/sounds).

entertainment proffered me by the goose clan. The formations passing over my house are now more frequently comprised of greater white-fronted geese. Their high pitched, yelping calls allow me to hear them approaching from a distance and bear little resemblance to the deep honks of their Canadian cousins (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Greater_White-fronted_Goose/sounds).

Of late, snow geese have taken to forming winter aggregations at Goose Pond. Later in the year, they will linger and rest there by the tens of

thousands. Their dispersal flights from the wetland are a thing to behold as echelon after echelon climb away and pass into the distance. At my place their high, nasal honks fill the air as they eagerly speed overhead bound for the bottomland corn fields to the west https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Snow_Goose/sounds).

I give a silent thanks to the goose species passing above me. They lighten the gloomy November skies with a reminder that the rhythms of nature still persist. Their calls and massed numbers are also proof that wildlife spectacles happen not just on TV but right around us, if we will only look.

These birds prompt me to recall the delightful observation conservationist Aldo Leopold made regarding our good fortune in hearing the conversation of geese overhead. As he watched Canada geese pass northward over his Wisconsin farmstead in the spring, he observed that, “. . . in this annual barter of food for light, and winter warmth for summer solitude, the whole continent receives as net profit a wild poem dropped from the murky skies upon the muds of March.”

Now, what to make of December? Here is a verse from Thomas Parson’s poem recognizing this month.

You are calm,

You allow me to slow,

To envelope the tranquility I crave.

The month seems a quiet one to me too. A good book and a hot cup of tea sound appropriate. Outside my window, nature has slowed too. I may see a white-tailed deer looking gray and showing its ribs wander by, pausing occasionally to nibble at a tree bud. It looks like mighty tough going out there.

Unlike the clamorous months that have just passed, the world seems to have gone strangely silent. Much of my December amusement from Mother Nature now comes in the form of the many woodpecker species inhabiting my woods. Shunning the warmth of more southern climes, they stick it out through the challenging winter. Utilizing their uncanny ability to detect insects and their larvae hidden within the woody tissue of the many diseased or dead trees around me, they persevere with admirable fortitude. They are a very busy bunch indeed.

My favorite is the pileated woodpecker. Strikingly huge (the size of a crow) with equally conspicuous plumage, they seem a good candidate for King of Woodpeckers. Their call rings loudly through the barren, otherwise somber forest. The wedge-shaped cavities they chop into trees are equally impressive due to their large size. Yes, I am quite happy to have pileated woodpeckers as close neighbors. They much enliven an otherwise quiet December (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Pileated_Woodpecker/sounds).

My favorite is the pileated woodpecker. Strikingly huge (the size of a crow) with equally conspicuous plumage, they seem a good candidate for King of Woodpeckers. Their call rings loudly through the barren, otherwise somber forest. The wedge-shaped cavities they chop into trees are equally impressive due to their large size. Yes, I am quite happy to have pileated woodpeckers as close neighbors. They much enliven an otherwise quiet December (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Pileated_Woodpecker/sounds).

January usually brings some visitors from the north. I see several sparrow species that have been absent since last winter. Fox sparrows, tree sparrows, white-crowned and white-throated sparrows work busily under my bird feeders. Dark-eyed juncos are here now too. Snowbirds my grandparents used to call them. The occasional yellow-bellied sapsucker joins the woodpecker fraternity that makes my woods their home.

These days I am fortunate enough to make my own migration. Heading south, we set our GPS for the “Nature Coast” of western Florida. Here, for a few weeks, we can forget the cold winds and leaden skies of winter-time  Indiana. A favored sound here is the high-pitched, piping, whistle of the osprey (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Osprey/sounds). What fun it is to watch them patrolling the Chasshowitzka, Homosassa, or Crystal Rivers in search of their piscine prey. There are brown pelicans to watch as they wheel and plunge-dive for fish

Indiana. A favored sound here is the high-pitched, piping, whistle of the osprey (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Osprey/sounds). What fun it is to watch them patrolling the Chasshowitzka, Homosassa, or Crystal Rivers in search of their piscine prey. There are brown pelicans to watch as they wheel and plunge-dive for fish  themselves. American white pelicans are here too. I wonder if I have seen any of these individuals at Goose Pond as, earlier in the year, they migrated southeast from their summer home in the northern Great Plains.

themselves. American white pelicans are here too. I wonder if I have seen any of these individuals at Goose Pond as, earlier in the year, they migrated southeast from their summer home in the northern Great Plains.

Of course there are many other distractions. Manatees congregate in the warmer freshwater springs of the area. Gopher tortoises and armadillos patrol the pines and scrub of the Withlacoochee State Forest. All in all it is, for Hoosier eyes, an exotic show that is provided by this brief winter escape to the subtropics.

An Indiana February, in spite of the continued cold weather, is a month with much merit for the naturalist. Although spring is technically weeks away, the first signs that nature is beginning to stir come this month. According to my field notes, mid-February is often heralded by the first, tentative, often feeble calls of the chorus frogs (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzePgnIpUuk). Surely, I think to myself, the icy grip of winter must be

An Indiana February, in spite of the continued cold weather, is a month with much merit for the naturalist. Although spring is technically weeks away, the first signs that nature is beginning to stir come this month. According to my field notes, mid-February is often heralded by the first, tentative, often feeble calls of the chorus frogs (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzePgnIpUuk). Surely, I think to myself, the icy grip of winter must be  easing if these tiny singers can manage to advertise their re-emergence into the world.

easing if these tiny singers can manage to advertise their re-emergence into the world.

There is action overhead too. Arriving a couple of weeks earlier than they did just a few years ago, come phalanx after phalanx of sandhill cranes. If I had to choose a bird species which above all others evokes wildness by voice alone, I should have to choose the call of these birds. How wild and far-carrying their rattling, bugling voice is (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpTykjLYYr0). Often times I search in vain for the source of these ancient, mesmerizing sounds coming from somewhere overhead. They are often too high, too far away for me to locate. Although unseen, their calls hang upon the air as if the biosphere itself was gifted with the ability to speak.

Their speech represents an exceptional story of conservation success. Once nearly extirpated east of the Mississippi, there are now almost 100,000 sandhill cranes in their eastern

Their speech represents an exceptional story of conservation success. Once nearly extirpated east of the Mississippi, there are now almost 100,000 sandhill cranes in their eastern  population. An evening spent just before sunset at Goose Pond FWA is an event to be recommended. The sight of thousands of sandhill cranes returning to their evening roost and filling the air with their announcements of arrival will, I guarantee, stir even the stodgiest soul.

population. An evening spent just before sunset at Goose Pond FWA is an event to be recommended. The sight of thousands of sandhill cranes returning to their evening roost and filling the air with their announcements of arrival will, I guarantee, stir even the stodgiest soul.

In March, the average daytime temperature has reached 530F and even the nights are often above freezing. I abhor the cold more and more with each passing year, what a relief this is. The wildlife around my rural home  respond too. Red-shouldered and Cooper’s hawks seem to find my little stand of timber to their liking as a nesting area. Both species are raucous and enthusiastic vocalizers and fill the day with their loud territorial and courtship calls (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Red-shouldered_Hawk/sounds /).

respond too. Red-shouldered and Cooper’s hawks seem to find my little stand of timber to their liking as a nesting area. Both species are raucous and enthusiastic vocalizers and fill the day with their loud territorial and courtship calls (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Red-shouldered_Hawk/sounds /).

(https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Coopers_Hawk/sounds)

We have owls too and their vocalizations continue in March. The hooting of  great-horned owls issues forth from our woods and is shortly answered by a neighbor across the road to the north (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great_Horned_Owl/sounds). “This is my spot says one. OK, but this is my spot over here,” says the other. Barred owls entertain us with their familiar “who cooks for you” call (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Barred_Owl/sounds).

great-horned owls issues forth from our woods and is shortly answered by a neighbor across the road to the north (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great_Horned_Owl/sounds). “This is my spot says one. OK, but this is my spot over here,” says the other. Barred owls entertain us with their familiar “who cooks for you” call (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Barred_Owl/sounds).

For some time, after moving to our house in the woods, we were puzzled by a night sound of exquisite eeriness. Our grandchildren were quite terrified by the creepiness of the calls we heard. But we eventually all agreed that we must go out into the pitch-black night and try to discover the source of our trepidation. The next time we heard the strange high-pitched call, which seemed to rise in pitch and then abruptly stop we armed ourselves with flashlights and ventured out. The voice was cryptically difficult to locate but we eventually traced it to a small redbud tree along the edge of our lawn. Shining our lights into the tree revealed the culprit –a barred owl (https://us.napster.com/artist/cornell-lab-of-ornithology/album/voices-of-north-american-owls-vol-2/track/barred-owl-female-solicitation-call). Our curiosity satisfied and our disquiets allayed, the grandkids and we can now listen with tranquility to the eerily strange solicitation call issuing from the nocturnal woodlands.

April, with its influx of returning migratory birds, offers a daily increase in participants joining the avian chorus outside the door. The morning chorus and warming temperatures are bound to lift one’s spirits after a long winter. But I am also heartened by the increasing number of amphibians adding their “two cents worth” to the chorale that is springtime Indiana. As noted, the chorus frogs got an early start. They were soon joined by wood frogs and spring peepers. Now, in April, I begin to also notice the voices of leopard frogs, green frogs, bullfrogs, gray tree frogs, and Fowler’s toads.

Just over a rise behind the house lies our neighbor’s pond. It isn’t long after the weather begins to really warm that my evenings will be enhanced by the pleasant buzzing of the countless Fowler’s toads which congregate there (www.youtube.com/watch?v=ezHxi2DEHOE). From now throughout much of the remainder of the summer, their odd falsetto bleats will provide palliative background music for a meditative sit on the front porch. The mating calls of bullfrogs will soon join the toad chorus (www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaP9cac3cPI). Their booming expressions reverberate across the wetlands reminding all who can hear that they are indeed the biggest frog in the puddle.

Just over a rise behind the house lies our neighbor’s pond. It isn’t long after the weather begins to really warm that my evenings will be enhanced by the pleasant buzzing of the countless Fowler’s toads which congregate there (www.youtube.com/watch?v=ezHxi2DEHOE). From now throughout much of the remainder of the summer, their odd falsetto bleats will provide palliative background music for a meditative sit on the front porch. The mating calls of bullfrogs will soon join the toad chorus (www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaP9cac3cPI). Their booming expressions reverberate across the wetlands reminding all who can hear that they are indeed the biggest frog in the puddle.

Come April, Anne and I will be enjoyably distracted by gray tree frogs which love to perch on our patio doors at night. How they seem to instinctively  know that porch lights attract insects is a mystery to me. But, there they are; hovering just beyond the lights ready to gulp down any passing midge or bug that makes the mistake of landing near them. Gray tree frogs are of two species, the eastern gray treefrog and Cope’s gray treefrog. They are differentiated by voice and it is mostly the latter which hangs around our home. Little snatches of song emanating from the surrounding trees are steady reminders of their presence out beyond our doors and windows (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=96W0crcrb_s).

know that porch lights attract insects is a mystery to me. But, there they are; hovering just beyond the lights ready to gulp down any passing midge or bug that makes the mistake of landing near them. Gray tree frogs are of two species, the eastern gray treefrog and Cope’s gray treefrog. They are differentiated by voice and it is mostly the latter which hangs around our home. Little snatches of song emanating from the surrounding trees are steady reminders of their presence out beyond our doors and windows (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=96W0crcrb_s).

One note of warning; I occasionally must relocate gray treefrogs who seem to love hiding under our outdoor grill cover. Once, after doing so, I proceeded to unthinkingly rub my eyes. The immediate result was a feeling akin to a shot of mild pepper to the face. Many amphibians have toxic skin secretions which protect them from predators. So does the gray treefrog I found.

May is a highly anticipated month at our house. We eagerly await the arrival of a migrant who will provide hours of free entertainment for the next few months. While its vocalizations are neither highly melodic nor exceptional, the physical abilities, agility, acrobatic mating displays, and sheer beauty of the ruby-throated hummingbird are second to none  (https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ruby-throated_Hummingbird/sounds). Although we usually try to anticipate their arrival by having feeders ready, these tiny motes of energy sometimes surprise us. We have, on a couple of occasions, awoken to find a hungry, early arrival hovering outside our bedroom window. Peering inside, it seems to be suggesting quite clearly “Hey, get your lazy butts out of bed and get that sugar water out here!”

(https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ruby-throated_Hummingbird/sounds). Although we usually try to anticipate their arrival by having feeders ready, these tiny motes of energy sometimes surprise us. We have, on a couple of occasions, awoken to find a hungry, early arrival hovering outside our bedroom window. Peering inside, it seems to be suggesting quite clearly “Hey, get your lazy butts out of bed and get that sugar water out here!”

June is a favored month. Some dependably warm weather brings an invitation to get outside. There is gardening, mowing, weeding and a hundred other chores to be done. I can cut back on trips to the gym; there will be lots of exercise from now until the frosty days of late fall.

There is a sound I associate from childhood with this pleasant, verdant month too. Sadly, it is a voice that is much less common than it once was. I speak of the clear, unmistakable call of the bobwhite. When I was a youngster, the voice of this little quail was an ever-present component of  life outside the house. Whether it was the high-pitched territorial “bob-white” or the melodic covey call used to group and stay in contact, their vocalizations were as fixed and familiar as the sun traversing the June sky https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Bobwhite/sounds. Sadly, years of habitat loss and fragmentation have caused their numbers to plummet by as much as 70-90%. Recently a covey near home comprised of nine birds flushed before me. I realized it was one of the larger I had seen in a while. But I also recognized it as a pitiful fraction of the numbers I encountered as a boy. I recall encountering coveys decades ago that often numbered 40 or 50 birds.

life outside the house. Whether it was the high-pitched territorial “bob-white” or the melodic covey call used to group and stay in contact, their vocalizations were as fixed and familiar as the sun traversing the June sky https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Bobwhite/sounds. Sadly, years of habitat loss and fragmentation have caused their numbers to plummet by as much as 70-90%. Recently a covey near home comprised of nine birds flushed before me. I realized it was one of the larger I had seen in a while. But I also recognized it as a pitiful fraction of the numbers I encountered as a boy. I recall encountering coveys decades ago that often numbered 40 or 50 birds.

Today the bobwhite is masquerading as a canary in our coal mine I’m afraid. I’m equally certain of two other things. The decline of the bobwhite in our time is permanent and sadly enough, most people won’t even notice the difference.

So, there you have it. You have seen one way in which I measure my year; one avenue for escaping the mind-disturbing inanities and frustrations of life in today’s world. These are months filled with gratitude at being able to still hear the persistent, calming melody of the Creation.

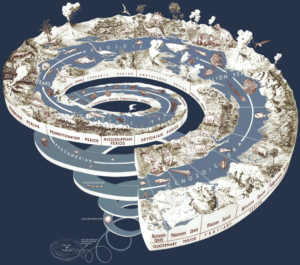

The ancestors of the katydids, crickets, and grasshoppers calling outside my window appear as fossils in Pennsylvanian aged rock formed from sediments laid down 300 million years ago. It comforts me to connect with earth’s deep history through listening to Nature. In this way, I am reminded that in an age of pandemics, inane politicians, personal and societal decisions abetted by scientific illiteracy, the natural world still plugs along. It has done so for a span of time that is incomprehensibly long. Nature will continue to do so in spite of the chaos and communal dysfunction which now seem to characterize our species, Homo sapiens.

The sounds and dramas of the natural world soothe us. They reconnect and re-center us emotionally. They do so by reminding us of our lengthy lineage as hunter-gatherers and our innate dependence upon the gifts of the natural world. They should also cause us to deeply reflect upon an observation made by Chief Thomas Rainwater. I paraphrase him here: “If we continue our assault on the planet’s ecosystems, Mother Earth is quite capable of – as a grazing bison might dislodge an annoying fly – simply shrugging us off and going it alone.”

Photo Credits:

wood thrush by Rhododendrites @ commons.wikimedia.org

Hudsonian godwit in Crossley's ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Hudsonian godwit migration map @ ResearchGate.net

Canada goose by Alan D. Wilson @ commons.wikimedia.org

greater white-fronted goose by Ken Conger @ commons.wikimedia.org

snow goose flock by Ray Hennessey @ commons.wikimedia.org

pileated woodpecker by Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren @ comm.wiki.org

chorus frog by Ohio Dept. of Nat. Res. @ commons.wikimedia.org

Fowler's toad by Aaron Sather @ commons.wikimedia.org

bobwhite quail by cuatok77 @ commons.wikimedia.org

All Other Photographs by the Author.

Globally the desert biome has its distinctive subdivisions. The Sonoran Desert of Arizona is the place to look for the saguaro cactus or the elf owl for example. To see Joshua trees or a desert tortoise one would venture into the Mojave. For a picturesque mixture of creosote bush, yucca, and ocotillo the Chihuahuan Desert of southwestern Texas is the place to be. The Great Basin Desert of Nevada offers vast stretches of sagebrush flats and the chance to catch a glimpse of a fleeing sagebrush vole.

Globally the desert biome has its distinctive subdivisions. The Sonoran Desert of Arizona is the place to look for the saguaro cactus or the elf owl for example. To see Joshua trees or a desert tortoise one would venture into the Mojave. For a picturesque mixture of creosote bush, yucca, and ocotillo the Chihuahuan Desert of southwestern Texas is the place to be. The Great Basin Desert of Nevada offers vast stretches of sagebrush flats and the chance to catch a glimpse of a fleeing sagebrush vole. The temperature in the spring season was not fearsomely high. The thermometer registered around 80F. In nearby Palm Springs, hundreds of feet lower in elevation, the daytime temperature was 95F. But summer would be a different story. In both places, the heat of the day can reach 120F. For humans, this makes hiking a questionable and potentially dangerous proposition. For the organisms that make this place their home, evolutionary adaptations for surviving such extremes of temperature and aridness are required.

The temperature in the spring season was not fearsomely high. The thermometer registered around 80F. In nearby Palm Springs, hundreds of feet lower in elevation, the daytime temperature was 95F. But summer would be a different story. In both places, the heat of the day can reach 120F. For humans, this makes hiking a questionable and potentially dangerous proposition. For the organisms that make this place their home, evolutionary adaptations for surviving such extremes of temperature and aridness are required. presence of a young chuckwalla lizard. Cautiously it climbed onto a prime basking spot atop an inviting granite boulder. Reptiles lack the physiological mechanisms mammals possess which automatically regulate their body temperatures. Ours for example hovers, without conscious effort, around the commonly expressed standard of 98.6F. Reptiles rely more on behavioral mechanisms and environmental factors to maintain their body temperature. Reptilian temperatures may fluctuate more than ours, but they can behaviorally keep their body temperature within a comparatively narrow, preferred range. The chuckwalla was using such behavioral mechanisms now. By basking in the sun and orienting its body for maximum exposure, the lizard was raising its body temperature to an optimum high. Having successfully warmed itself, the chuckwalla could more efficiently hunt for prey. Should the lizard become too hot, it would resort to shade-seeking behavior to reduce its temperature.

presence of a young chuckwalla lizard. Cautiously it climbed onto a prime basking spot atop an inviting granite boulder. Reptiles lack the physiological mechanisms mammals possess which automatically regulate their body temperatures. Ours for example hovers, without conscious effort, around the commonly expressed standard of 98.6F. Reptiles rely more on behavioral mechanisms and environmental factors to maintain their body temperature. Reptilian temperatures may fluctuate more than ours, but they can behaviorally keep their body temperature within a comparatively narrow, preferred range. The chuckwalla was using such behavioral mechanisms now. By basking in the sun and orienting its body for maximum exposure, the lizard was raising its body temperature to an optimum high. Having successfully warmed itself, the chuckwalla could more efficiently hunt for prey. Should the lizard become too hot, it would resort to shade-seeking behavior to reduce its temperature. Another desert dweller soon made an appearance. From beneath a cluster of hedgehog cacti, a small chipmunk-like squirrel appeared. Busily searching the ground for fallen seeds, fruits, and insects was a white-tailed antelope squirrel. Upon finding an appealing morsel, the squirrel sat upon its hind legs and, in typical squirrel fashion, manipulated the food with its forepaws. The underside of its tail, a startlingly white color and perfect for reflecting the sun’s rays, was arched over its back to act as a sunshade.

Another desert dweller soon made an appearance. From beneath a cluster of hedgehog cacti, a small chipmunk-like squirrel appeared. Busily searching the ground for fallen seeds, fruits, and insects was a white-tailed antelope squirrel. Upon finding an appealing morsel, the squirrel sat upon its hind legs and, in typical squirrel fashion, manipulated the food with its forepaws. The underside of its tail, a startlingly white color and perfect for reflecting the sun’s rays, was arched over its back to act as a sunshade. mere glancing about revealed beavertail and hedgehog cactus in bloom. Huge spikes of Mojave yucca flowers surged upward and were being heavily visited by bees searching for pollen or nectar. Mariposa lily, desert paintbrush, apricot mallow, and ocotillo flowers added to the mosaic of colors visible around us. It was akin to sitting in a garden painting by Monet, albeit one with a sense of propriety regarding flaunting one’s rich colors too extravagantly.

mere glancing about revealed beavertail and hedgehog cactus in bloom. Huge spikes of Mojave yucca flowers surged upward and were being heavily visited by bees searching for pollen or nectar. Mariposa lily, desert paintbrush, apricot mallow, and ocotillo flowers added to the mosaic of colors visible around us. It was akin to sitting in a garden painting by Monet, albeit one with a sense of propriety regarding flaunting one’s rich colors too extravagantly.

can encounter every year, as opposed to the species which erupt periodically.

can encounter every year, as opposed to the species which erupt periodically. one, she will deliver a sting which paralyzes the hapless cicada. Given the size of the cicada relative to the wasp, I find it amazing that the cicada killer is able to fly back to the burrow carrying its inert victim. Into one of the side chambers, she will drag the paralyzed cicada.

one, she will deliver a sting which paralyzes the hapless cicada. Given the size of the cicada relative to the wasp, I find it amazing that the cicada killer is able to fly back to the burrow carrying its inert victim. Into one of the side chambers, she will drag the paralyzed cicada.

something like twenty different species of such animals. They vary in size. The smallest is the six-inch-long pink fairy armadillo. These little fellows are found in Argentina.

something like twenty different species of such animals. They vary in size. The smallest is the six-inch-long pink fairy armadillo. These little fellows are found in Argentina. At the other extreme is the giant armadillo which reaches a length of three feet and weighs over seventy pounds. This species has a wide range and is found in several South American countries including Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru.

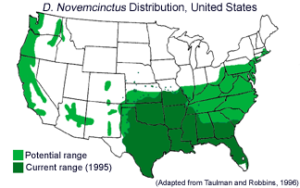

At the other extreme is the giant armadillo which reaches a length of three feet and weighs over seventy pounds. This species has a wide range and is found in several South American countries including Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru. How far will armadillos expand their range? According to the website Armadillo Online, cold winter temperatures and annual rainfall (at least 15 in./year needed) are major factors limiting distribution. The website features a 1995 map of the potential range expansion for the nine-banded armadillo. Note that Porter County, Indiana is already farther north than then predicted.

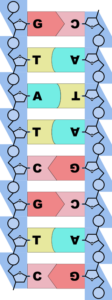

How far will armadillos expand their range? According to the website Armadillo Online, cold winter temperatures and annual rainfall (at least 15 in./year needed) are major factors limiting distribution. The website features a 1995 map of the potential range expansion for the nine-banded armadillo. Note that Porter County, Indiana is already farther north than then predicted. identical cells. This is not unusual. That’s the way our early embryological development begins too. But, in armadillos, each of these four cells then goes on to independently develop into a fetus. Thereafter (about four months) the female gives birth to four identical quadruplets, clones of each other in other words. Apparently female nine-banded armadillos do this every time.

identical cells. This is not unusual. That’s the way our early embryological development begins too. But, in armadillos, each of these four cells then goes on to independently develop into a fetus. Thereafter (about four months) the female gives birth to four identical quadruplets, clones of each other in other words. Apparently female nine-banded armadillos do this every time.

Gazing into one of the aquarium tanks, I considered the strangeness of the sea anemones. In these photos, there are at least five different species. In the world’s oceans, there are over 1,000 different kinds. For a

Gazing into one of the aquarium tanks, I considered the strangeness of the sea anemones. In these photos, there are at least five different species. In the world’s oceans, there are over 1,000 different kinds. For a mobile species like us, how odd it seems to be non-motile, stuck in one place. Equally curious would be having a body with no head, no back, no front, no rear. Sea anemones have radial symmetry. I wonder what that would feel like?

mobile species like us, how odd it seems to be non-motile, stuck in one place. Equally curious would be having a body with no head, no back, no front, no rear. Sea anemones have radial symmetry. I wonder what that would feel like? The clown fishes which brazenly swim among the anemone’s tentacles represent an interesting ecological relationship known as mutualism. In this type of symbiosis, both animals receive benefit from their association. The fishes, while shielded from being stung by a thick coating of mucus, receive protection from predators. The anemone benefits from the clown fishes’ wastes which fertilize the algae growing symbiotically inside the anemones (a whole other fascinating story of mutualism). Clown fishes may also remove parasites from the anemone or lure prey within reach of the anemone’s tentacles.

The clown fishes which brazenly swim among the anemone’s tentacles represent an interesting ecological relationship known as mutualism. In this type of symbiosis, both animals receive benefit from their association. The fishes, while shielded from being stung by a thick coating of mucus, receive protection from predators. The anemone benefits from the clown fishes’ wastes which fertilize the algae growing symbiotically inside the anemones (a whole other fascinating story of mutualism). Clown fishes may also remove parasites from the anemone or lure prey within reach of the anemone’s tentacles. of life can be centered upon a coral reef. Corals (>6000 species) are animals too. Their bodies resemble tiny sea anemones but are noted for their ability to secrete a

of life can be centered upon a coral reef. Corals (>6000 species) are animals too. Their bodies resemble tiny sea anemones but are noted for their ability to secrete a protective, limestone, exoskeleton. Some, such as brain corals and the mushroom coral are solitary and live in their own small, isolated colonies.

protective, limestone, exoskeleton. Some, such as brain corals and the mushroom coral are solitary and live in their own small, isolated colonies. creatures (>2000 species) have the same radial symmetry, simplicity of body form, and lack of organ systems. But they can move. The mesmerizing pulsating of their “bells” forces out the water within, a practical application of Newton’s Third Law of Motion. Their tentacles also bear stinging nematocyst cells. Some, like the infamous box jellyfish, inject toxins capable of killing a human.

creatures (>2000 species) have the same radial symmetry, simplicity of body form, and lack of organ systems. But they can move. The mesmerizing pulsating of their “bells” forces out the water within, a practical application of Newton’s Third Law of Motion. Their tentacles also bear stinging nematocyst cells. Some, like the infamous box jellyfish, inject toxins capable of killing a human.

giant squid. Nevertheless, I learned that this animal (of which there are several species) was real and is, in fact, considered the largest invertebrate animal in the world. The giant squid can be over 40 ft. long (mostly tentacle length). The closely related colossal squid is bulkier with a record weight of over half a ton.

giant squid. Nevertheless, I learned that this animal (of which there are several species) was real and is, in fact, considered the largest invertebrate animal in the world. The giant squid can be over 40 ft. long (mostly tentacle length). The closely related colossal squid is bulkier with a record weight of over half a ton.

The octopuses also intrigue me greatly. Zoologists consider them to be the most intelligent of all invertebrates. Cuttlefishes and squids also have large brain to body size ratios, but octopuses are the star pupils. Their brains are said to contain as many neurons as a mouse’s brain.

The octopuses also intrigue me greatly. Zoologists consider them to be the most intelligent of all invertebrates. Cuttlefishes and squids also have large brain to body size ratios, but octopuses are the star pupils. Their brains are said to contain as many neurons as a mouse’s brain.

The beach at Piedras Blancas in coastal California was populated, on the day of my visit, by hundreds of elephant seals. The big bulls were far out to sea so it was females, juvenile males, and young of the year who populated the dark sands. May was molting time for this group and the coats of many resembled a tattered old jacket that should have been discarded long ago. Occasionally a couple of young bulls would begin to feel their oats and a brief barking, shoving, sparring match would ensue. These were but a preview of the fierce, blood-drawing contests in which the big bulls would engage when they returned in late fall. Only the biggest, strongest males could hope to achieve the rank of beach master and be rewarded with the assembling of a harem of 20 to 50 females.

The beach at Piedras Blancas in coastal California was populated, on the day of my visit, by hundreds of elephant seals. The big bulls were far out to sea so it was females, juvenile males, and young of the year who populated the dark sands. May was molting time for this group and the coats of many resembled a tattered old jacket that should have been discarded long ago. Occasionally a couple of young bulls would begin to feel their oats and a brief barking, shoving, sparring match would ensue. These were but a preview of the fierce, blood-drawing contests in which the big bulls would engage when they returned in late fall. Only the biggest, strongest males could hope to achieve the rank of beach master and be rewarded with the assembling of a harem of 20 to 50 females. Blancas, it was common to see their skin marred by the scars of a cookie cutter shark bite. More serious threats to the elephant seals are killer whales and great white sharks. Occasionally one will see a seal bearing a large shark bite mark; the sign of a narrow escape from death.

Blancas, it was common to see their skin marred by the scars of a cookie cutter shark bite. More serious threats to the elephant seals are killer whales and great white sharks. Occasionally one will see a seal bearing a large shark bite mark; the sign of a narrow escape from death. During dives and surfacing, the vibrissae are held back against the face. At depths, while hunting, they are fanned out to better detect any movement of the water molecules. How is this possible? Could I grow my beard and, with closed eyes, hope to detect the passing of a swallow using only the hair of my face? Even though I have learned these research-derived facts about elephant seals, their behavior still seems miraculous. Finding food in the pitch black ocean depths seems an unintelligible, mystical power to me. The cold, the blackness, the vast volume of water to be searched; how amazing their adaptations and survival skills are.

During dives and surfacing, the vibrissae are held back against the face. At depths, while hunting, they are fanned out to better detect any movement of the water molecules. How is this possible? Could I grow my beard and, with closed eyes, hope to detect the passing of a swallow using only the hair of my face? Even though I have learned these research-derived facts about elephant seals, their behavior still seems miraculous. Finding food in the pitch black ocean depths seems an unintelligible, mystical power to me. The cold, the blackness, the vast volume of water to be searched; how amazing their adaptations and survival skills are. What a handsome little creature is the ring-necked snake. Small by serpent standards, they average around ten inches in total length. Their dorsal coloration is a dark, blackish gray with a bright yellow ring around their neck. While their back is somberly colored, much like the pieces of shale under which I often find them, their bellies are a flamboyant yellow or orange.

What a handsome little creature is the ring-necked snake. Small by serpent standards, they average around ten inches in total length. Their dorsal coloration is a dark, blackish gray with a bright yellow ring around their neck. While their back is somberly colored, much like the pieces of shale under which I often find them, their bellies are a flamboyant yellow or orange.

different strategy. Not on the rock-strewn slopes must I search. Instead, it is the small lakes that fill some of the valleys I must investigate. Adult red-spotted newts are aquatic salamanders. Larval newts have gills just as other salamanders and frogs do. But as adults they have lungs. If I lie very quietly at the edge of one of the small ponds on my land, I may be rewarded by seeing a newt lazily float to the surface for a tiny breath of air. If I give myself away, it will very quickly make a U-turn and, with undulations of its oar-like tail, make a crash dive toward the bottom. Introducing oneself to a newt requires patience.

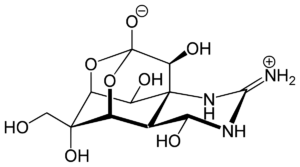

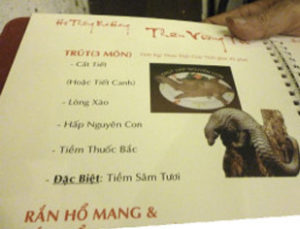

different strategy. Not on the rock-strewn slopes must I search. Instead, it is the small lakes that fill some of the valleys I must investigate. Adult red-spotted newts are aquatic salamanders. Larval newts have gills just as other salamanders and frogs do. But as adults they have lungs. If I lie very quietly at the edge of one of the small ponds on my land, I may be rewarded by seeing a newt lazily float to the surface for a tiny breath of air. If I give myself away, it will very quickly make a U-turn and, with undulations of its oar-like tail, make a crash dive toward the bottom. Introducing oneself to a newt requires patience. Tetrodotoxin is one of the most deadly neurotoxins known. You might be familiar with it as the toxic ingredient in fugu, the Japanese puffer fish delicacy. Tetrodotoxin is found in the bite of the potentially deadly Pacific blue-ringed octopus as well. Who would have thought that our little Hoosier-dwelling newt had anything in common with two of the most notoriously venomous animals in the world?

Tetrodotoxin is one of the most deadly neurotoxins known. You might be familiar with it as the toxic ingredient in fugu, the Japanese puffer fish delicacy. Tetrodotoxin is found in the bite of the potentially deadly Pacific blue-ringed octopus as well. Who would have thought that our little Hoosier-dwelling newt had anything in common with two of the most notoriously venomous animals in the world?

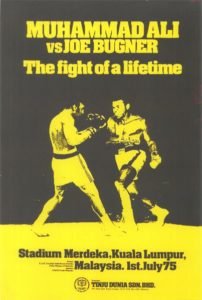

fisherman had drawn up their vessels. Luck was with us. The third fisherman we queried said yes; he would take us out to Pulau Perhentian and come back and pick us up in three days. The negotiated price (to be paid when he came back for us) was 50 Ringgit (about US$23 at that time).

fisherman had drawn up their vessels. Luck was with us. The third fisherman we queried said yes; he would take us out to Pulau Perhentian and come back and pick us up in three days. The negotiated price (to be paid when he came back for us) was 50 Ringgit (about US$23 at that time). water, was a great hammerhead shark many feet in length. The distinctive chocolate-brown back broke the water barely a dozen feet from our boat. As suddenly as it had appeared, the shark was gone. We excitedly congratulated each other’s good fortune in seeing such an extraordinary animal. Inwardly each of us reflected upon the possibility that this fellow might have friends swimming the waters closer to our island destination.

water, was a great hammerhead shark many feet in length. The distinctive chocolate-brown back broke the water barely a dozen feet from our boat. As suddenly as it had appeared, the shark was gone. We excitedly congratulated each other’s good fortune in seeing such an extraordinary animal. Inwardly each of us reflected upon the possibility that this fellow might have friends swimming the waters closer to our island destination.

Stretching before me was a multicolored vista of corals. There were rounded forms of solitary corals like Fungia (looking a bit like a mushroom cap) and the aptly named brain coral with its ridged and furrowed cerebral-like form. There were fan-shaped corals, branching corals like Acropora (staghorn), and corals that were soft instead of stony. Underlying all these were the reef-building corals. Their growth over the millennia had produced the limestone bulwark of the reef. Even now the living polyp animals covering the reef surfaces were working away. Their tentacled, tubular bodies were busily converting carbon, calcium, and oxygen into the stony skeletons we recognize as the reef. One might suppose that all this variety existed in a uniform, concrete-like color but this was not so. Scanning the reef, I could see animals of purple, blue, red, yellow, black, and brown. Each color represented a different species of reef organism. Here and there, embedded in the reef itself, I could see individuals of Tridacna, the giant clam. The reef had

Stretching before me was a multicolored vista of corals. There were rounded forms of solitary corals like Fungia (looking a bit like a mushroom cap) and the aptly named brain coral with its ridged and furrowed cerebral-like form. There were fan-shaped corals, branching corals like Acropora (staghorn), and corals that were soft instead of stony. Underlying all these were the reef-building corals. Their growth over the millennia had produced the limestone bulwark of the reef. Even now the living polyp animals covering the reef surfaces were working away. Their tentacled, tubular bodies were busily converting carbon, calcium, and oxygen into the stony skeletons we recognize as the reef. One might suppose that all this variety existed in a uniform, concrete-like color but this was not so. Scanning the reef, I could see animals of purple, blue, red, yellow, black, and brown. Each color represented a different species of reef organism. Here and there, embedded in the reef itself, I could see individuals of Tridacna, the giant clam. The reef had  literally grown around the larger ones imprisoning them in stone. By periodically opening and closing their shells, they had created a snug space within the reef for themselves. The monstrous clams (the largest ever found weighed over 500 lbs.) lie there with their valves agape filtering water through their mantle cavity in the constant need for freshly oxygenated water and planktonic food.

literally grown around the larger ones imprisoning them in stone. By periodically opening and closing their shells, they had created a snug space within the reef for themselves. The monstrous clams (the largest ever found weighed over 500 lbs.) lie there with their valves agape filtering water through their mantle cavity in the constant need for freshly oxygenated water and planktonic food. caterpillar. Other kinds were nearly two feet in length with tan, spiny skin. All of them crept about on tiny, suction-creating tube feet as they vacuumed up sand and sorted from it the organic detritus which fed them. Arthropods such as shrimp and lobsters prowled the surface of the coral and probed its many crannies in their search for a meal or a secretive hiding spot.

caterpillar. Other kinds were nearly two feet in length with tan, spiny skin. All of them crept about on tiny, suction-creating tube feet as they vacuumed up sand and sorted from it the organic detritus which fed them. Arthropods such as shrimp and lobsters prowled the surface of the coral and probed its many crannies in their search for a meal or a secretive hiding spot. unimagined role of Nemo). These retreated seductively into their sea anemone homes as they attempted to lure me – just another big fish to them – into the poisonous tentacles of the anemones. There were exquisitely colored butterfly fish, their little

unimagined role of Nemo). These retreated seductively into their sea anemone homes as they attempted to lure me – just another big fish to them – into the poisonous tentacles of the anemones. There were exquisitely colored butterfly fish, their little  beak-like snouts probing the corals for algae and plankton. Parrot fish, with their massive teeth exposed in a perpetual smile, cruised over the coral.

beak-like snouts probing the corals for algae and plankton. Parrot fish, with their massive teeth exposed in a perpetual smile, cruised over the coral.

carried out a series of experiments by which he hoped to understand the effects of high population density on the social behavior of rats and mice.

carried out a series of experiments by which he hoped to understand the effects of high population density on the social behavior of rats and mice.

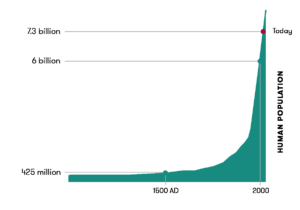

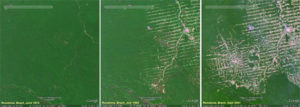

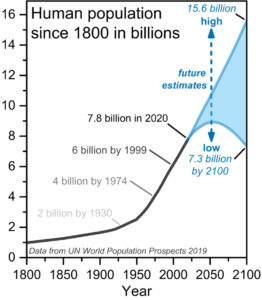

density has increased much over time? It has been estimated that the planet’s human population in 1000 A.D was around 310,000,000. About 47% of earth’s land surface (24,642,757 sq. mi.) is habitable; this is the area that excludes deserts, mountains, etc. (zo.utexas.edu/courses/Thoc/land.html). These figures give us a population density of 12.5 people/sq. mi. at that time. The human population of earth is now around 7,600,000,000. The result is an average population density of 308 people/sq. mi. of habitable land. This is a 2,464% increase in human population density on habitable land over a period of ten centuries. So yes, human population density has increased dramatically over time.

density has increased much over time? It has been estimated that the planet’s human population in 1000 A.D was around 310,000,000. About 47% of earth’s land surface (24,642,757 sq. mi.) is habitable; this is the area that excludes deserts, mountains, etc. (zo.utexas.edu/courses/Thoc/land.html). These figures give us a population density of 12.5 people/sq. mi. at that time. The human population of earth is now around 7,600,000,000. The result is an average population density of 308 people/sq. mi. of habitable land. This is a 2,464% increase in human population density on habitable land over a period of ten centuries. So yes, human population density has increased dramatically over time. many. Research suggests that our human ancestors lived in social groups of around 150 people; as do several hunter-gatherer societies currently (Dunbar, 1992). Dunbar further proposed that when group size exceeds this number, the group becomes unstable and begins to fragment. Dunbar believes that the size of the human neocortex limits the brain’s information processing capacity and this limits the number of relationships an individual can monitor simultaneously. Therefore functional group size is limited to around 150 among primates. Could this mean that the progression toward our own behavioral sink is inevitable simply because we have far exceeded the ideal human global population size (and social structure) thus creating social complexities that our minds are incapable of efficiently processing?

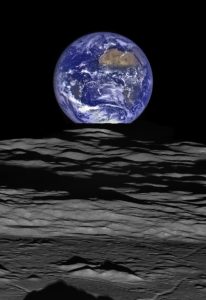

many. Research suggests that our human ancestors lived in social groups of around 150 people; as do several hunter-gatherer societies currently (Dunbar, 1992). Dunbar further proposed that when group size exceeds this number, the group becomes unstable and begins to fragment. Dunbar believes that the size of the human neocortex limits the brain’s information processing capacity and this limits the number of relationships an individual can monitor simultaneously. Therefore functional group size is limited to around 150 among primates. Could this mean that the progression toward our own behavioral sink is inevitable simply because we have far exceeded the ideal human global population size (and social structure) thus creating social complexities that our minds are incapable of efficiently processing? In the meantime, let us recall that less than 500 generations ago all human ancestors were hunter-gatherers whose survival depended upon a deep connection to, an understanding of, and a reverence for the natural world. This relationship is instinctively deep-rooted within us yet. A simple walk in a forest still enthralls us and enhances our mood. How many still enjoy the solitude, scenery, and rewards of our favorite fishing spot, spring mushroom woods, city park, or camping spot? The huge crowds which nowadays surge into our state and national parks offer proof that we still yearn for our ancestral connection to nature. Think about how we are drawn as if magnetically to the ocean surf. Consider our inclination to stand in wonderment as we gaze upon magnificent vistas such as the Tetons, Yosemite Valley, the Grand Canyon, or the Milky Way as it fills the pitch-black, night sky. Yes, in the interim, there are ways to lighten the stresses put upon us by modern human society. There are ways to regain our sanity. They lie just outside our door.

In the meantime, let us recall that less than 500 generations ago all human ancestors were hunter-gatherers whose survival depended upon a deep connection to, an understanding of, and a reverence for the natural world. This relationship is instinctively deep-rooted within us yet. A simple walk in a forest still enthralls us and enhances our mood. How many still enjoy the solitude, scenery, and rewards of our favorite fishing spot, spring mushroom woods, city park, or camping spot? The huge crowds which nowadays surge into our state and national parks offer proof that we still yearn for our ancestral connection to nature. Think about how we are drawn as if magnetically to the ocean surf. Consider our inclination to stand in wonderment as we gaze upon magnificent vistas such as the Tetons, Yosemite Valley, the Grand Canyon, or the Milky Way as it fills the pitch-black, night sky. Yes, in the interim, there are ways to lighten the stresses put upon us by modern human society. There are ways to regain our sanity. They lie just outside our door.

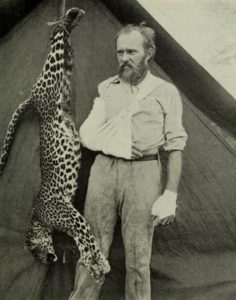

Jones-type adventurer/explorer/big game hunter. Such a story should be expected from a man who killed an attacking leopard with his bare hands. His book is still a fascinating narrative although the recounting of his hunts of charismatic animals, such as elephants and gorillas, will trouble many readers.

Jones-type adventurer/explorer/big game hunter. Such a story should be expected from a man who killed an attacking leopard with his bare hands. His book is still a fascinating narrative although the recounting of his hunts of charismatic animals, such as elephants and gorillas, will trouble many readers. But back to the story; it was during one hunt in Africa that Akeley himself learned just how quietly and craftily an elephant can approach a pursuer. Hunting for museum specimens, he was stalking a group of three bulls. Akeley at last heard the crashing sounds of feeding coming from a bamboo forest 200 yards ahead. Pausing to appraise the rifle and cartridges his gun-bearer had handed him, Akeley: was suddenly conscious that an elephant was almost on top of me. I have no knowledge of how the warning came. I have no mental record of hearing him, seeing him, or of any warning from the gun boy. . . My next mental record is of a tusk right at my chest. Akeley instinctively grabbed the tusk and swung in between the two. This he had practiced in his mind in anticipation of such an attack and he believed this “rehearsing” is what saved his life.

But back to the story; it was during one hunt in Africa that Akeley himself learned just how quietly and craftily an elephant can approach a pursuer. Hunting for museum specimens, he was stalking a group of three bulls. Akeley at last heard the crashing sounds of feeding coming from a bamboo forest 200 yards ahead. Pausing to appraise the rifle and cartridges his gun-bearer had handed him, Akeley: was suddenly conscious that an elephant was almost on top of me. I have no knowledge of how the warning came. I have no mental record of hearing him, seeing him, or of any warning from the gun boy. . . My next mental record is of a tusk right at my chest. Akeley instinctively grabbed the tusk and swung in between the two. This he had practiced in his mind in anticipation of such an attack and he believed this “rehearsing” is what saved his life. which the presenter spoke about the use of Asian elephants in the logging industry in Thailand. One particular slide stuck in my mind. It showed a male under restraint (one leg chained to a tree) because he was in musth. Musth is the male elephant’s equivalent to the female heat cycle. During musth, the testosterone levels of the male become elevated many fold. The temporal glands on each side of the head produce pheromones which dampen the side of the bull’s head. Additional they tend to produce a constant stream of urine which wets their hind legs and thus marks the path of their wonderings. Woe to a younger, weaker male who crosses this track.

which the presenter spoke about the use of Asian elephants in the logging industry in Thailand. One particular slide stuck in my mind. It showed a male under restraint (one leg chained to a tree) because he was in musth. Musth is the male elephant’s equivalent to the female heat cycle. During musth, the testosterone levels of the male become elevated many fold. The temporal glands on each side of the head produce pheromones which dampen the side of the bull’s head. Additional they tend to produce a constant stream of urine which wets their hind legs and thus marks the path of their wonderings. Woe to a younger, weaker male who crosses this track. saw many elephants. How exciting to finally get to see these fascinating creatures up close as they browsed, tended their young, enjoyed a dust bat, or simply rested in the shade of an immense sausage tree. Here I experienced firsthand the storied silence with which they can move.

saw many elephants. How exciting to finally get to see these fascinating creatures up close as they browsed, tended their young, enjoyed a dust bat, or simply rested in the shade of an immense sausage tree. Here I experienced firsthand the storied silence with which they can move. glanced to the right, a young male elephant walked by our vehicle. Although this four-ton animal was within a few yards of the Land Rover, not a hint of the sound of footfall could I detect. It was abruptly very clear to me how one could be focused upon something else, as Akeley had been, and have one of these huge animals stealthily and suddenly materialize upon you. Quite an eye-opening experience it was.

glanced to the right, a young male elephant walked by our vehicle. Although this four-ton animal was within a few yards of the Land Rover, not a hint of the sound of footfall could I detect. It was abruptly very clear to me how one could be focused upon something else, as Akeley had been, and have one of these huge animals stealthily and suddenly materialize upon you. Quite an eye-opening experience it was. I chose The Silence of Elephants as the title for this composition for another reason too. Not hearing elephants is now more often due to the simple fact that their numbers have been so drastically reduced. This is true in both Asia and Africa. As an example, when we finally reached Tarangire N.P., we had our best success seeing elephants, over 100 in a couple of days’ time. But Akeley, in his aforementioned book, reported seeing 700 elephants in just one, single herd. This was in the early 1900’s

I chose The Silence of Elephants as the title for this composition for another reason too. Not hearing elephants is now more often due to the simple fact that their numbers have been so drastically reduced. This is true in both Asia and Africa. As an example, when we finally reached Tarangire N.P., we had our best success seeing elephants, over 100 in a couple of days’ time. But Akeley, in his aforementioned book, reported seeing 700 elephants in just one, single herd. This was in the early 1900’s without them. As researchers have come to know more about them, the argument against killing elephants has grown stronger. We now know that there is much going on within that big brain of theirs, the largest of any land mammal.

without them. As researchers have come to know more about them, the argument against killing elephants has grown stronger. We now know that there is much going on within that big brain of theirs, the largest of any land mammal.

Heavea brasiliensis trees. Each tree bore the familiar, sloping, parallel grooves of the rubber tapper’s awl. A small cup rested upon each trunk, ready to capture the dripping latex spawned by the tapper’s delicate gouging of the bark. Plantations such as these made Malaysia one of the world’s top exporters of natural rubber. Down the valley, interspersed between palm and rubber, were sprinkled the kampong houses of the Malay rice growers. These houses,

Heavea brasiliensis trees. Each tree bore the familiar, sloping, parallel grooves of the rubber tapper’s awl. A small cup rested upon each trunk, ready to capture the dripping latex spawned by the tapper’s delicate gouging of the bark. Plantations such as these made Malaysia one of the world’s top exporters of natural rubber. Down the valley, interspersed between palm and rubber, were sprinkled the kampong houses of the Malay rice growers. These houses, beautiful in their rustic simplicity, stood above the ground on stilts. Not only did this keep the home above a potential flood, such a design made entry rather more difficult for unwelcome house guests such as scorpions, centipedes, and Indian cobras. Built above the ground, the homes were also more likely to catch cooling breezes. In a home with no electricity, this is no small matter. After all this is a land where the daily temperature hovers in the mid-nineties and the humidity approaches one hundred percent. The houses often featured a high-pitched roof covered by attap palm thatch. This design rapidly shed the rain and allowed hot air to rise above the floor-level living spaces. All in all, the houses’ clever designs gave a distinct quality of bucolic beauty, minimalism, and comfort.

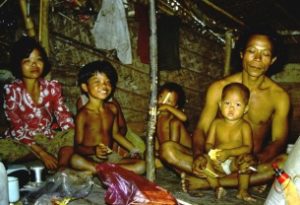

beautiful in their rustic simplicity, stood above the ground on stilts. Not only did this keep the home above a potential flood, such a design made entry rather more difficult for unwelcome house guests such as scorpions, centipedes, and Indian cobras. Built above the ground, the homes were also more likely to catch cooling breezes. In a home with no electricity, this is no small matter. After all this is a land where the daily temperature hovers in the mid-nineties and the humidity approaches one hundred percent. The houses often featured a high-pitched roof covered by attap palm thatch. This design rapidly shed the rain and allowed hot air to rise above the floor-level living spaces. All in all, the houses’ clever designs gave a distinct quality of bucolic beauty, minimalism, and comfort. those who would view the valley only from the road. This secreted realm concealed a tiny village inhabited by Temuan aborigines. It was a piece of the world which clearly conveyed to me the realization that I was in a realm totally alien to anything I had previously experienced. It was a microcosmic piece of planet earth totally foreign to me in every way. The language, methods of procuring food, mode of dress, habits of hygiene, and spiritual beliefs of the Temuan were all utterly novel to me.

those who would view the valley only from the road. This secreted realm concealed a tiny village inhabited by Temuan aborigines. It was a piece of the world which clearly conveyed to me the realization that I was in a realm totally alien to anything I had previously experienced. It was a microcosmic piece of planet earth totally foreign to me in every way. The language, methods of procuring food, mode of dress, habits of hygiene, and spiritual beliefs of the Temuan were all utterly novel to me. half feet in height; the women closer to five feet. Their small stature was an expression of Bergmann’s Rule. This zoological principle holds that mammals (humans included) which live in the tropics tend to have smaller bodies than those that live at higher latitudes. This is because smaller mammals, somewhat counter-intuitively, have more surface (skin) area in relationship to body volume than larger ones. Having greater surface area allows for more efficient radiation of body heat and thus a greater ability to stay cool in the tropical heat. I can attest to the efficacy of this body form. On multiple hikes, I would find myself wearing sweat-soaked clothing so wet it looked as if I had fallen into a stream. Meanwhile, the skin of my Temuan companions always seemed to stay amazingly dry. Several thousand years of natural selection can work its adaptive genius on humans just as well as any other species.

half feet in height; the women closer to five feet. Their small stature was an expression of Bergmann’s Rule. This zoological principle holds that mammals (humans included) which live in the tropics tend to have smaller bodies than those that live at higher latitudes. This is because smaller mammals, somewhat counter-intuitively, have more surface (skin) area in relationship to body volume than larger ones. Having greater surface area allows for more efficient radiation of body heat and thus a greater ability to stay cool in the tropical heat. I can attest to the efficacy of this body form. On multiple hikes, I would find myself wearing sweat-soaked clothing so wet it looked as if I had fallen into a stream. Meanwhile, the skin of my Temuan companions always seemed to stay amazingly dry. Several thousand years of natural selection can work its adaptive genius on humans just as well as any other species. their village until three years later, when I had to bid them a reluctant adieu, they were ever gracious and accepting of my presence among them. Their skills in traversing the forest were unparalleled. How, I wondered, did they avoid becoming disoriented and lost in this vast, green world? To my eye, the forest appeared uniform in every direction I looked; dangerously so for a solo novice. I once asked them how they accomplished their amazing navigation. Their answer, while patently obvious to them, did little to illuminate this uncanny ability for me. “We just know where to go,“ was their cryptic explanation of this incredible orienteering ability.

their village until three years later, when I had to bid them a reluctant adieu, they were ever gracious and accepting of my presence among them. Their skills in traversing the forest were unparalleled. How, I wondered, did they avoid becoming disoriented and lost in this vast, green world? To my eye, the forest appeared uniform in every direction I looked; dangerously so for a solo novice. I once asked them how they accomplished their amazing navigation. Their answer, while patently obvious to them, did little to illuminate this uncanny ability for me. “We just know where to go,“ was their cryptic explanation of this incredible orienteering ability. cup he had fashioned from a section of giant bamboo. The skillfulness with which the Temuan were able to manipulate objects in their environment into articles of utilitarian use simply defied imagination. Never before had I encountered a people so connected, so resourceful, so intimately coupled with the natural world.

cup he had fashioned from a section of giant bamboo. The skillfulness with which the Temuan were able to manipulate objects in their environment into articles of utilitarian use simply defied imagination. Never before had I encountered a people so connected, so resourceful, so intimately coupled with the natural world. trackers, hunters, herbalists, and story-tellers atrophied. Caught in limbo between the old way of life and Malaysia’s rapid ascension into the modern world of commerce, the younger generation of Temuan was not adept at either. Ten thousand years as slash and burn agrarians and hunter-gatherers leave one ill prepared for a job in the contemporary world. Starting work at 7:00A sharp means little to a people who have never had a clock. The eight hour shift is incomprehensible to a people who have for millennia eaten, slept, hunted, and socialized in accord with rhythms not of the clock but of the corpus and the forest. Dodong had no need for literacy to fully understand all this. His innate intelligence and sense of place told him all he needed to know.

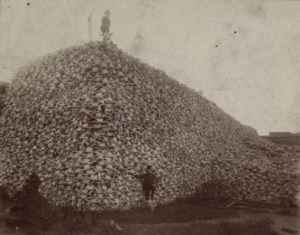

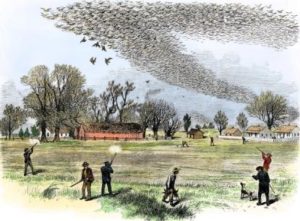

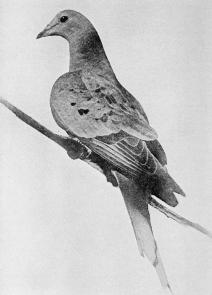

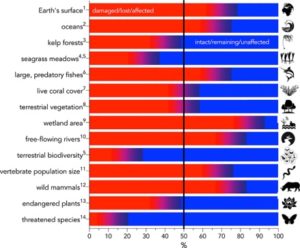

trackers, hunters, herbalists, and story-tellers atrophied. Caught in limbo between the old way of life and Malaysia’s rapid ascension into the modern world of commerce, the younger generation of Temuan was not adept at either. Ten thousand years as slash and burn agrarians and hunter-gatherers leave one ill prepared for a job in the contemporary world. Starting work at 7:00A sharp means little to a people who have never had a clock. The eight hour shift is incomprehensible to a people who have for millennia eaten, slept, hunted, and socialized in accord with rhythms not of the clock but of the corpus and the forest. Dodong had no need for literacy to fully understand all this. His innate intelligence and sense of place told him all he needed to know. wood fire; eating snakes, monkeys, or insects; dying from an infection easily cured by an antibiotic they say. Doubtless there is merit to their argument. Who am I to say that the forest may be a better home than one with plumbing and electricity? What privilege have I to suggest the young Temuan shouldn’t have at least a chance to wear Nike® running shoes, own a smart phone, watch television, or clad themselves in Outerwear® when these things are readily available to me? I have no reasoned answer as to why my aboriginal friends are not equally entitled to have more.