Some may find it difficult to understand my outburst of exhilaration upon encountering a mere frog. Nevertheless, I must plead guilty. First, this was a species of animal I had never seen before, always an event of significance for a naturalist! And then, this was no ordinary frog. Here was an anuran which held near legendary status among those of us infected with an insatiable, incurable fascination with the natural world. Yes, despite the passage of nearly five decades, my first glimpse of a Wallace’s flying frog remains a delightful, much-cherished memory.

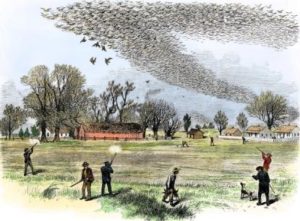

A frog that can fly? Impossible! Surely this is a creature of myth, it was thought. And yet, in the middle of the 19th century, British biologist Alfred R. Wallace confirmed what the Indigenous people of Indo-Malaya had long known. There existed a tropical rainforest frog that could travel from tree to tree in an unprecedented manner.

Granted, to say that the frog flies is a bit misleading. True, flapping flight is the province of insects, bats, and birds (and the extinct pterosaurs). So, to be precise, Wallace’s flying frog is a glider. But even this skill sets it apart. In our minds, we picture frogs as creatures of the sodden wetlands. They are corpulent, lethargic, sit and wait hunters. Not so the specimen passed into my hands by Oha, my Temuan indigene friend, those many years ago. Here was a frog whose large, slim body, and long limbs bespoke athleticism. This was a creature not of the soppy marshes but an adventurous denizen of the rainforest canopy.

And its appearance was so beyond the norm. The body of the specimen I held was nearly four inches long, a good size for a frog. But even more striking was its coloration and adaptive, anatomical flourishes.

A base color of green was to be expected; excellent camouflage in a world exhibiting an embarrassment of green hues. But the subtle gradations into yellow on the flanks and limbs, the strikingly jet-black webbing of the feet, the light spots on the torso which mimicked sun-dapples seemed to go above and beyond the mere adaptive. I could not resist the inclination to see the frog as not just as a superb example of natural selection, but as an object of exquisite beauty. Once again, as I have on many occasions, I was moved to ask: why does Nature create such breathtaking beauty when it seems to far exceed what is necessary for survival?

Along the forearms, flanges of soft tissue extended outward and provided greater surface area, more aerodynamic lifting surface. The toes were elongated and the webbing between them was extensive. Gently spreading the digits of the feet, I beheld four huge parachutes. Here were the secrets to the uncanny mechanism the frog used to move through its tropical rainforest world.

Imagine you’re a small creature living high in the treetops of a dense forest. To survive, you need to find food, attract a mate, and lay eggs—all while moving from tree to tree. Climbing down to the forest floor and back up again each time would be slow, exhausting, and dangerous, especially with predators lurking below.

The evolution of the ability to glide from one tree to the next would be of great selective advantage. The journey would be quicker, offer less exposure to ground predators, and consume much less energy. Thus, through accumulated adaptations over time, Nature has gifted us Wallace’s flying frog. A leap into space, a spreading of the toe membranes of the feet, and we have a glider capable of parachuting through the forest canopy in a method both highly controlled and efficient.

As I became more familiar with the remarkable biodiversity of the Malaysian rainforest, I was amazed to discover that gliding was not unique to this particular frog. Several other vertebrate species had independently evolved specialized anatomical adaptations that enabled them to glide through the forest canopy.

Once, standing on the veranda of our biological field station, I saw a small animal sail across the lawn, suddenly swoop upward, and plop itself onto a tree trunk at the yard’s edge. The speed and directional control of its glide had misled me. What I had assumed to be a bird carrying a strand of nesting material was, to my surprise, a small agamid lizard, its long tail trailing behind. Known taxonomically as Draco, it was one of over three dozen species of so-called flying lizards.

Once, standing on the veranda of our biological field station, I saw a small animal sail across the lawn, suddenly swoop upward, and plop itself onto a tree trunk at the yard’s edge. The speed and directional control of its glide had misled me. What I had assumed to be a bird carrying a strand of nesting material was, to my surprise, a small agamid lizard, its long tail trailing behind. Known taxonomically as Draco, it was one of over three dozen species of so-called flying lizards.

The Draco lizards are joined by nearly a dozen different kinds of geckos that have also evolved gliding ability. Remarkably enough, there are even a few species of snakes living in the Indo-Malayan region that can glide.

The Draco lizards are joined by nearly a dozen different kinds of geckos that have also evolved gliding ability. Remarkably enough, there are even a few species of snakes living in the Indo-Malayan region that can glide.

In Malaysia, I found that there are also around a dozen squirrels that have gliding ability. An extravagance compared to the single species of flying squirrel I was familiar with back in Indiana. All told, I found the southeast Asian rainforests were home to dozens of different kinds of gliding animals representing three different vertebrate Classes – the Amphibia, the Reptilia, and the Mammalia. What an amazing assemblage!

After leaving Malaysia, I had the good fortune to visit tropical rainforests in Central and South America. I soon found myself questioning, “Where are all the rainforest gliders?” I saw none, nor did I hear mention of any from my incredibly knowledgeable guides. Why are there so many kinds of gliding animals in SE Asia but not here, I wondered? Seeking an answer to this question led me down a fascinating investigative trail.

As I further considered the fauna of places like Costa Rica, Panama, Ecuador, and Peru, I discovered that gliders essentially did not exist here. How did this compare with the tropical rainforest of equatorial Africa, I wondered? Turns out, there is a scarcity of gliders there too. Only a few species of flying squirrels have evolved this ability. Why would such a unique and useful method of locomotion evolve only in the tropical rainforests of Asia and nowhere else?

As you might guess, I wasn’t the first biologist to ponder this puzzling question. Others interested in this question began by asking whether the plant structure of the tropical rainforests of Asia, Africa, and South America might be different. Maybe some physical features of these forests could act to favor certain mutations or recombinations of animal genes. Such permutations of the genetic code could lead to the adaptive evolution of gliding behavior.

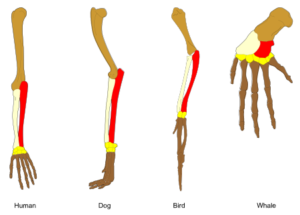

Useful modifications might include more extensive webbing of the toes, the ability to flatten the body into an airfoil, growth of excess skin along the sides which could function as patagia (airfoils of skin), or elongation of the ribs to support the skin of the patagia. Even the behavioral inclination to make broad leaps between trees would be adaptive.

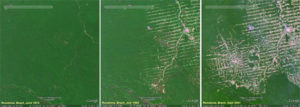

Tropical rainforests of the world look surprisingly similar when flying above them. I have always thought they look like a vast, Brobdingnagian garden of broccoli heads lying far below. Stretching to the horizon one sees mile upon mile of rounded, puffy, green crowns of various hues. But this is misleading.

In reality, given the vast distances between them, we should guess that the tree species comprising the forests of Asia, Africa, and South America would be different. If so, maybe the physical structure of the forests would be different as well. Sure enough, when zoologists seeking answers to the evolution of gliding behavior examined the three forests closely, differences in their structure were observed.

Researchers detected a major distinction among these three tropical rainforest areas of the world regarding the distribution of lianas within them. Lianas are woody, vining plants rooted in the ground. They use trees as scaffolding to grow into the canopy. In this high tier of the forest, their leaves can receive more sunlight for photosynthesis.

In African rainforests, lianas grow densely near the ground and can make up over 40% of the plant life. This thick, tangled growth would make gliding difficult. But the lianas do make for an easy and efficient way to climb into and among the trees. Here gliding would not be that advantageous. It is more practical to just use the vines as stairways.

The rainforests of Central and South America—known as the Neotropics—are also full of lianas. These vines create natural pathways for climbing animals but also block the open space needed for gliding. As a result, climbing is the more favorable adaptation. Locals even call a commonly encountered liana “escalera de mono”—Spanish for “monkey ladder”. Perhaps this illuminates an intuitive understanding of the role lianas play in arboreal travel.

In contrast, Southeast Asian rainforests—like those in Borneo—have far fewer lianas. One study found they make up less than 15% of the woody plants. With fewer vines to climb and fewer obstacles in the air, gliding becomes a much more helpful way to travel between trees. In these forests, animals that glide may have a real advantage. Thus, the so-called selective pressure for the evolution of gliding would be high.

Another physical factor favoring the evolution of gliding was found during this research. The average height of the trees in SE Asia is significantly greater than in Africa or South America. The forests of Malaysia, for example, have many tree species that grow to heights of 165 to 200 feet. Some emergent trees may tower over 250 feet above the forest floor. In Amazonia and equatorial Africa, maximum heights of 150 feet or so are more common.

There is a simple, direct relationship between the height at which a glide is undertaken and the distance an animal can travel. The higher the launch, the greater the distance which can be covered. Perhaps being able to utilize higher “launch pads”, and thus make longer glides, is also a selective factor favoring the evolution of gliding in SE Asian forests. In rainforests with trees of less average height, gliding might not offer such a distinct advantage.

Perhaps the potential for long glides provided by the greater tree height in these forests, coupled with the paucity of lianas, act in concert to provide a powerful selective pressure in favor of gliding. This hypothesis may explain why only the rainforests of Asia have produced such a bewildering assemblage of gliding vertebrates while the forests of South America and Africa have not.

Attentiveness, curiosity, and the habit of asking questions can lead us down some truly fascinating paths. These are skills worth cultivating, as they often spark one discovery after another. You, dear reader, may have little interest in becoming a biologist—and that’s perfectly fine. But consider this: the living world offers endless opportunities for contemplation and wonder. Qualities like alertness, a sense of awe in the presence of earth’s seemingly infinite biodiversity, and the impulse to ask why or how can enrich the life of any nonscientist. Try them out on your next walk in the woods or moment beneath the sky. You may find your world growing a little larger, a lot more interesting, and perhaps even a touch more enchanting.

______________________________________________________________________

Photo Credits: Draco with “wings” extended by the author Kuhl’s flying gecko by Bernard DuPont @ commons.wikimedia.org paradise tree snake by Rushed/Thai Natl. Parks @ commons.wikimedia.org Interested in a deeper dive?

-

Emmons, Louise H. and A.H. Gentry. 1983. Tropical forest structure and the distribution of gliding and prehensile-tailed vertebrates. The American Naturalist. -

Forsyth, Adrian. 1990. Portraits of the Rainforest. Pp 66-67. Camden House. North York, Ontario.

ecotourism. The last six miles of road into “our” fazenda, the Refugio da Ilha, consisted of a narrow, gravel track which traversed a mixture of pastureland and cerrado, the palm-dotted savannah of Brazil. Occasionally in the distance, the absurdly beautiful, pink blossoms of a Tabeuia or trumpet tree could be seen

ecotourism. The last six miles of road into “our” fazenda, the Refugio da Ilha, consisted of a narrow, gravel track which traversed a mixture of pastureland and cerrado, the palm-dotted savannah of Brazil. Occasionally in the distance, the absurdly beautiful, pink blossoms of a Tabeuia or trumpet tree could be seen

tree along the roadway. With a body length of just over three feet, these are the largest of the parrot species. Stunningly beautiful, as well as endangered, these parrots were near the top of our list of hoped-for bird sightings.

tree along the roadway. With a body length of just over three feet, these are the largest of the parrot species. Stunningly beautiful, as well as endangered, these parrots were near the top of our list of hoped-for bird sightings. spacious collection of sleeping quarters, sitting rooms, dining areas, and kitchens. The ranch was set upon ten thousand acres of Brazilian real estate. Twenty-five hundred acres of this expanse were devoted to cattle ranching, while the remaining seventy-five hundred formed a vast and beguiling nature preserve.

spacious collection of sleeping quarters, sitting rooms, dining areas, and kitchens. The ranch was set upon ten thousand acres of Brazilian real estate. Twenty-five hundred acres of this expanse were devoted to cattle ranching, while the remaining seventy-five hundred formed a vast and beguiling nature preserve. ponds were festooned with basking spectacled caimans. Along one side of the lawn ran a small, gently flowing river called the Salobra. This tiny river was to provide many hours of delightful wildlife viewing in the days to come.

ponds were festooned with basking spectacled caimans. Along one side of the lawn ran a small, gently flowing river called the Salobra. This tiny river was to provide many hours of delightful wildlife viewing in the days to come. come. The food was mouthwateringly good. Beef ribs cooked over the wood fire were accompanied by fried egg plant, rice and beans (ever-present in Central and South American meals), corn, manioc, and beets. How wonderful such a simple, but well-prepared meal can be when it is supplemented by a sharp hunger and is taken outside in a sublime setting. As we dined under the shade trees, we chatted with the adult children of the ranch’s owners and heard plans for our first outing on the reserve.

come. The food was mouthwateringly good. Beef ribs cooked over the wood fire were accompanied by fried egg plant, rice and beans (ever-present in Central and South American meals), corn, manioc, and beets. How wonderful such a simple, but well-prepared meal can be when it is supplemented by a sharp hunger and is taken outside in a sublime setting. As we dined under the shade trees, we chatted with the adult children of the ranch’s owners and heard plans for our first outing on the reserve. wide, level, and passed through highly productive wetland habitat. It was along these elevated pathways that we took our first stroll through the Pantanal.

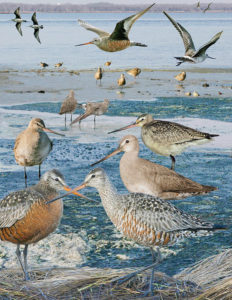

wide, level, and passed through highly productive wetland habitat. It was along these elevated pathways that we took our first stroll through the Pantanal. themselves unseen, the avian residents of the wetland showed no such hesitancy. They were more than willing to flaunt their gorgeous plumage and diversity of form. The fact that birds are, unlike many other animal groups, often easily seen and simultaneously beautiful, makes birding one of the most popular outdoor activities in the world. We saw dozens of species on that first walk. There is a thrill, as well as a sense of satisfaction, in seeing a previously unseen bird species. On this walk I saw my

themselves unseen, the avian residents of the wetland showed no such hesitancy. They were more than willing to flaunt their gorgeous plumage and diversity of form. The fact that birds are, unlike many other animal groups, often easily seen and simultaneously beautiful, makes birding one of the most popular outdoor activities in the world. We saw dozens of species on that first walk. There is a thrill, as well as a sense of satisfaction, in seeing a previously unseen bird species. On this walk I saw my first rufescent tiger heron, first snail kite, first wood rail, first black-hooded parakeet. Each one was a reminder that the biological diversity of our amazing planet is even greater than we imagine.

first rufescent tiger heron, first snail kite, first wood rail, first black-hooded parakeet. Each one was a reminder that the biological diversity of our amazing planet is even greater than we imagine. There are few more enjoyable ways to reconnoiter new territory than by water. With minimal exertion (thanks to a worthy boatman), and in stealthy silence, one is free to drift along devoting full attention to each new scene looming around the bend.

There are few more enjoyable ways to reconnoiter new territory than by water. With minimal exertion (thanks to a worthy boatman), and in stealthy silence, one is free to drift along devoting full attention to each new scene looming around the bend. downstream toward us were two chunky, furry, brown periscopes. Warily sizing us up, came a pair of giant river otters. Intermittently scanning their surroundings, by means of this characteristic periscoping behavior, and diving with sinuous grace, the otters passed by within feet of us.

downstream toward us were two chunky, furry, brown periscopes. Warily sizing us up, came a pair of giant river otters. Intermittently scanning their surroundings, by means of this characteristic periscoping behavior, and diving with sinuous grace, the otters passed by within feet of us. rounding a bend in the stream, we were confronted by a pair of black howler monkeys alternately wading and swimming the narrow channel. Suddenly, finding us upon them, the howlers hurried on with what looked like wide-eyed terror. Doubtless they were uncomfortable at having to ford the stream in the first place. Almost certainly the presence of caiman and anaconda in these waters made swimming an exceedingly risky proposition, and one to be avoided when possible.

rounding a bend in the stream, we were confronted by a pair of black howler monkeys alternately wading and swimming the narrow channel. Suddenly, finding us upon them, the howlers hurried on with what looked like wide-eyed terror. Doubtless they were uncomfortable at having to ford the stream in the first place. Almost certainly the presence of caiman and anaconda in these waters made swimming an exceedingly risky proposition, and one to be avoided when possible. island off our port side. There, lying in the sun, was a yellow anaconda. The snake was hesitant to give up its basking spot and allowed us to beach our canoes and closely approach. While not nearly as large as its cousin the green anaconda (>20 ft. potentially), this was still a snake of impressive proportions and quite capable of taking a young caiman or capybara.

island off our port side. There, lying in the sun, was a yellow anaconda. The snake was hesitant to give up its basking spot and allowed us to beach our canoes and closely approach. While not nearly as large as its cousin the green anaconda (>20 ft. potentially), this was still a snake of impressive proportions and quite capable of taking a young caiman or capybara. with only their eyes and nostrils above water, the caimans were virtually invisible. A tremendous cannonball-like splash, a drenching cascade of water, and an olive-green blur disappearing beneath the surface would often be our indications that we had nearly beached ourselves upon a caiman.

with only their eyes and nostrils above water, the caimans were virtually invisible. A tremendous cannonball-like splash, a drenching cascade of water, and an olive-green blur disappearing beneath the surface would often be our indications that we had nearly beached ourselves upon a caiman. tremendously overgrown guinea pig, these mammals are the largest rodents in the world. They may weigh over one-hundred pounds and stand nearly two feet tall at the shoulder. Capybaras are semiaquatic plant eaters and for them the water is not only a source of food but provides an effective escape from predators such as the jaguar. Capybaras are social animals, and it was not unusual to see small herds of them grazing at what they considered a safe distance from the water’s edge.

tremendously overgrown guinea pig, these mammals are the largest rodents in the world. They may weigh over one-hundred pounds and stand nearly two feet tall at the shoulder. Capybaras are semiaquatic plant eaters and for them the water is not only a source of food but provides an effective escape from predators such as the jaguar. Capybaras are social animals, and it was not unusual to see small herds of them grazing at what they considered a safe distance from the water’s edge. with wonder to the sound of a tropical downpour rapidly advancing my way through the forest. It is the sound of millions of raindrops falling upon millions of leaves. The volume grows and I silently give thanks not only for the thatched palm above my head but my great good fortune in being in this moment.

with wonder to the sound of a tropical downpour rapidly advancing my way through the forest. It is the sound of millions of raindrops falling upon millions of leaves. The volume grows and I silently give thanks not only for the thatched palm above my head but my great good fortune in being in this moment. my territory; here is my troop”, transports me to the magnificent dipterocarp forest of Malaysia. I feel the intense humidity. I smell the fecund odor of the rainforest. I marvel at its rich biodiversity. I stand enthralled as I contemplate such a richness springing from some long-ago stellar cataclysm.

my territory; here is my troop”, transports me to the magnificent dipterocarp forest of Malaysia. I feel the intense humidity. I smell the fecund odor of the rainforest. I marvel at its rich biodiversity. I stand enthralled as I contemplate such a richness springing from some long-ago stellar cataclysm. Arizona. Through the dry, clear desert air I scan the forest of giant saguaros. In vain I struggle to declare a victor in the contest to determine which one really is the most magnificent of its kind.

Arizona. Through the dry, clear desert air I scan the forest of giant saguaros. In vain I struggle to declare a victor in the contest to determine which one really is the most magnificent of its kind. They do so every year at about this time, October and November. And herein lie my questions. How do they know when it is time to visit? What mysterious instinct tells them when shingle and pin oak acorns have ripened? By what strange skill are they able to identify the oaks among the maples, hickories, and poplars which surround them? Clearly, they possess these abilities. I listen to the steady rain of small, round acorns plopping onto the undergrowth, pinging off the metal roof of the garage, and peppering my driveway. Many must be consumed by the birds, but their aggressive frenzy of feeding results in seemingly just as many being mishandled and dropped.

They do so every year at about this time, October and November. And herein lie my questions. How do they know when it is time to visit? What mysterious instinct tells them when shingle and pin oak acorns have ripened? By what strange skill are they able to identify the oaks among the maples, hickories, and poplars which surround them? Clearly, they possess these abilities. I listen to the steady rain of small, round acorns plopping onto the undergrowth, pinging off the metal roof of the garage, and peppering my driveway. Many must be consumed by the birds, but their aggressive frenzy of feeding results in seemingly just as many being mishandled and dropped. Ornithologists have now discovered that most birds have a decent ability to discern odors, and some have an exceptionally keen sense of smell. The turkey vulture can locate, by smell, a rotting animal carcass a mile away for example. Could it be that the odor of ripe acorns, carried upon the wind, can be detected by my grackle visitors?

Ornithologists have now discovered that most birds have a decent ability to discern odors, and some have an exceptionally keen sense of smell. The turkey vulture can locate, by smell, a rotting animal carcass a mile away for example. Could it be that the odor of ripe acorns, carried upon the wind, can be detected by my grackle visitors?

nervous system organ. This so-called rostrum, armed with thousands of mechanical and electrical sensors, can detect the movements as well as the bioelectric aura of their prey. Thus, their bill allows them to hunt and capture prey such as aquatic insects, worms, and crustaceans even in opaque, murky waters. Can you imagine being able to detect another person, stealthily hiding in a totally darkened room, by sensing the bioelectric aura pulsing over their skin surface?

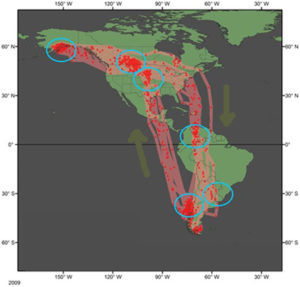

nervous system organ. This so-called rostrum, armed with thousands of mechanical and electrical sensors, can detect the movements as well as the bioelectric aura of their prey. Thus, their bill allows them to hunt and capture prey such as aquatic insects, worms, and crustaceans even in opaque, murky waters. Can you imagine being able to detect another person, stealthily hiding in a totally darkened room, by sensing the bioelectric aura pulsing over their skin surface? terrain. Yet some animals exhibit the uncanny ability to traverse these vast seas and arrive at a desired spot just as a potential food source becomes abundant. Consider the tiger shark. With a length that may exceed sixteen feet, it is one of the ocean’s largest apex predators.

terrain. Yet some animals exhibit the uncanny ability to traverse these vast seas and arrive at a desired spot just as a potential food source becomes abundant. Consider the tiger shark. With a length that may exceed sixteen feet, it is one of the ocean’s largest apex predators. Then there are the puzzles of animal communication to consider. In the late 1990’s Caitlan O’Connell-Rodwell discovered that African elephants could communicate using seismic waves transmitted through the ground. Special receptors in their feet allow the elephants to detect distant running, stopping, or aggressive charging by their compatriots. In addition, she found that elephants produce very low frequency (infrasonic), airborne vocal sounds. Such sounds are below the threshold of human hearing. This type of sound also produces vibrations in the ground. Thus, elephants can use both their ears and feet as organs of hearing. Infrasounds can be perceived from distances as great as five or six miles. This allows elephants to communicate even when far out of sight of one another. What they may be saying remains to be understood. They have really big brains. One might suspect conversations of significant complexity.

Then there are the puzzles of animal communication to consider. In the late 1990’s Caitlan O’Connell-Rodwell discovered that African elephants could communicate using seismic waves transmitted through the ground. Special receptors in their feet allow the elephants to detect distant running, stopping, or aggressive charging by their compatriots. In addition, she found that elephants produce very low frequency (infrasonic), airborne vocal sounds. Such sounds are below the threshold of human hearing. This type of sound also produces vibrations in the ground. Thus, elephants can use both their ears and feet as organs of hearing. Infrasounds can be perceived from distances as great as five or six miles. This allows elephants to communicate even when far out of sight of one another. What they may be saying remains to be understood. They have really big brains. One might suspect conversations of significant complexity. Wolves are apex predators, literally top “dogs”. They hunt in packs because of their focus upon very large, potentially dangerous prey species such as moose. Mammalian predators in general are highly intelligent and clever. They are keen observers of the behaviors displayed by their target animals. Predators are quick to note prey which have an injured limb, exhibit unnatural posture, move in an uncoordinated manner, or emit the odor of an infected wound. Such signs reveal a lessened ability to defend against attack.

Wolves are apex predators, literally top “dogs”. They hunt in packs because of their focus upon very large, potentially dangerous prey species such as moose. Mammalian predators in general are highly intelligent and clever. They are keen observers of the behaviors displayed by their target animals. Predators are quick to note prey which have an injured limb, exhibit unnatural posture, move in an uncoordinated manner, or emit the odor of an infected wound. Such signs reveal a lessened ability to defend against attack. moose in this case, may be based upon something other than these obviously debilitating conditions. Whether a moose appears healthy or not, there is often an initial, face to face meeting with its foe. Wolf and prey remain stationary as they share an intense stare with one another. What may happen next is often curious. After this period of seemingly cross-species assessment the wolf, or wolves, may simply turn and walk off. In other cases, it is the moose that calmly wanders away from a wolf pack. Alternatively the moose may choose to run, in which case it will almost assuredly be attacked. In other cases, after the stare-down, the wolves may suddenly charge and kill the moose within minutes.

moose in this case, may be based upon something other than these obviously debilitating conditions. Whether a moose appears healthy or not, there is often an initial, face to face meeting with its foe. Wolf and prey remain stationary as they share an intense stare with one another. What may happen next is often curious. After this period of seemingly cross-species assessment the wolf, or wolves, may simply turn and walk off. In other cases, it is the moose that calmly wanders away from a wolf pack. Alternatively the moose may choose to run, in which case it will almost assuredly be attacked. In other cases, after the stare-down, the wolves may suddenly charge and kill the moose within minutes. warmth and body odor as we passed by. A tree in a nearby forest under attack by insects may transmit airborne, organic, chemical warning signals to its nearby neighbors. In response, these trees may begin to preemptively produce their own toxic or foul-tasting anti-insect defensive compounds.

warmth and body odor as we passed by. A tree in a nearby forest under attack by insects may transmit airborne, organic, chemical warning signals to its nearby neighbors. In response, these trees may begin to preemptively produce their own toxic or foul-tasting anti-insect defensive compounds.

Globally the desert biome has its distinctive subdivisions. The Sonoran Desert of Arizona is the place to look for the saguaro cactus or the elf owl for example. To see Joshua trees or a desert tortoise one would venture into the Mojave. For a picturesque mixture of creosote bush, yucca, and ocotillo the Chihuahuan Desert of southwestern Texas is the place to be. The Great Basin Desert of Nevada offers vast stretches of sagebrush flats and the chance to catch a glimpse of a fleeing sagebrush vole.

Globally the desert biome has its distinctive subdivisions. The Sonoran Desert of Arizona is the place to look for the saguaro cactus or the elf owl for example. To see Joshua trees or a desert tortoise one would venture into the Mojave. For a picturesque mixture of creosote bush, yucca, and ocotillo the Chihuahuan Desert of southwestern Texas is the place to be. The Great Basin Desert of Nevada offers vast stretches of sagebrush flats and the chance to catch a glimpse of a fleeing sagebrush vole. The temperature in the spring season was not fearsomely high. The thermometer registered around 80F. In nearby Palm Springs, hundreds of feet lower in elevation, the daytime temperature was 95F. But summer would be a different story. In both places, the heat of the day can reach 120F. For humans, this makes hiking a questionable and potentially dangerous proposition. For the organisms that make this place their home, evolutionary adaptations for surviving such extremes of temperature and aridness are required.

The temperature in the spring season was not fearsomely high. The thermometer registered around 80F. In nearby Palm Springs, hundreds of feet lower in elevation, the daytime temperature was 95F. But summer would be a different story. In both places, the heat of the day can reach 120F. For humans, this makes hiking a questionable and potentially dangerous proposition. For the organisms that make this place their home, evolutionary adaptations for surviving such extremes of temperature and aridness are required. presence of a young chuckwalla lizard. Cautiously it climbed onto a prime basking spot atop an inviting granite boulder. Reptiles lack the physiological mechanisms mammals possess which automatically regulate their body temperatures. Ours for example hovers, without conscious effort, around the commonly expressed standard of 98.6F. Reptiles rely more on behavioral mechanisms and environmental factors to maintain their body temperature. Reptilian temperatures may fluctuate more than ours, but they can behaviorally keep their body temperature within a comparatively narrow, preferred range. The chuckwalla was using such behavioral mechanisms now. By basking in the sun and orienting its body for maximum exposure, the lizard was raising its body temperature to an optimum high. Having successfully warmed itself, the chuckwalla could more efficiently hunt for prey. Should the lizard become too hot, it would resort to shade-seeking behavior to reduce its temperature.

presence of a young chuckwalla lizard. Cautiously it climbed onto a prime basking spot atop an inviting granite boulder. Reptiles lack the physiological mechanisms mammals possess which automatically regulate their body temperatures. Ours for example hovers, without conscious effort, around the commonly expressed standard of 98.6F. Reptiles rely more on behavioral mechanisms and environmental factors to maintain their body temperature. Reptilian temperatures may fluctuate more than ours, but they can behaviorally keep their body temperature within a comparatively narrow, preferred range. The chuckwalla was using such behavioral mechanisms now. By basking in the sun and orienting its body for maximum exposure, the lizard was raising its body temperature to an optimum high. Having successfully warmed itself, the chuckwalla could more efficiently hunt for prey. Should the lizard become too hot, it would resort to shade-seeking behavior to reduce its temperature. Another desert dweller soon made an appearance. From beneath a cluster of hedgehog cacti, a small chipmunk-like squirrel appeared. Busily searching the ground for fallen seeds, fruits, and insects was a white-tailed antelope squirrel. Upon finding an appealing morsel, the squirrel sat upon its hind legs and, in typical squirrel fashion, manipulated the food with its forepaws. The underside of its tail, a startlingly white color and perfect for reflecting the sun’s rays, was arched over its back to act as a sunshade.

Another desert dweller soon made an appearance. From beneath a cluster of hedgehog cacti, a small chipmunk-like squirrel appeared. Busily searching the ground for fallen seeds, fruits, and insects was a white-tailed antelope squirrel. Upon finding an appealing morsel, the squirrel sat upon its hind legs and, in typical squirrel fashion, manipulated the food with its forepaws. The underside of its tail, a startlingly white color and perfect for reflecting the sun’s rays, was arched over its back to act as a sunshade. mere glancing about revealed beavertail and hedgehog cactus in bloom. Huge spikes of Mojave yucca flowers surged upward and were being heavily visited by bees searching for pollen or nectar. Mariposa lily, desert paintbrush, apricot mallow, and ocotillo flowers added to the mosaic of colors visible around us. It was akin to sitting in a garden painting by Monet, albeit one with a sense of propriety regarding flaunting one’s rich colors too extravagantly.

mere glancing about revealed beavertail and hedgehog cactus in bloom. Huge spikes of Mojave yucca flowers surged upward and were being heavily visited by bees searching for pollen or nectar. Mariposa lily, desert paintbrush, apricot mallow, and ocotillo flowers added to the mosaic of colors visible around us. It was akin to sitting in a garden painting by Monet, albeit one with a sense of propriety regarding flaunting one’s rich colors too extravagantly.

can encounter every year, as opposed to the species which erupt periodically.

can encounter every year, as opposed to the species which erupt periodically. one, she will deliver a sting which paralyzes the hapless cicada. Given the size of the cicada relative to the wasp, I find it amazing that the cicada killer is able to fly back to the burrow carrying its inert victim. Into one of the side chambers, she will drag the paralyzed cicada.

one, she will deliver a sting which paralyzes the hapless cicada. Given the size of the cicada relative to the wasp, I find it amazing that the cicada killer is able to fly back to the burrow carrying its inert victim. Into one of the side chambers, she will drag the paralyzed cicada.

something like twenty different species of such animals. They vary in size. The smallest is the six-inch-long pink fairy armadillo. These little fellows are found in Argentina.

something like twenty different species of such animals. They vary in size. The smallest is the six-inch-long pink fairy armadillo. These little fellows are found in Argentina. At the other extreme is the giant armadillo which reaches a length of three feet and weighs over seventy pounds. This species has a wide range and is found in several South American countries including Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru.

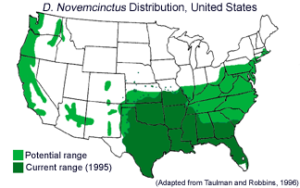

At the other extreme is the giant armadillo which reaches a length of three feet and weighs over seventy pounds. This species has a wide range and is found in several South American countries including Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru. How far will armadillos expand their range? According to the website Armadillo Online, cold winter temperatures and annual rainfall (at least 15 in./year needed) are major factors limiting distribution. The website features a 1995 map of the potential range expansion for the nine-banded armadillo. Note that Porter County, Indiana is already farther north than then predicted.

How far will armadillos expand their range? According to the website Armadillo Online, cold winter temperatures and annual rainfall (at least 15 in./year needed) are major factors limiting distribution. The website features a 1995 map of the potential range expansion for the nine-banded armadillo. Note that Porter County, Indiana is already farther north than then predicted. identical cells. This is not unusual. That’s the way our early embryological development begins too. But, in armadillos, each of these four cells then goes on to independently develop into a fetus. Thereafter (about four months) the female gives birth to four identical quadruplets, clones of each other in other words. Apparently female nine-banded armadillos do this every time.

identical cells. This is not unusual. That’s the way our early embryological development begins too. But, in armadillos, each of these four cells then goes on to independently develop into a fetus. Thereafter (about four months) the female gives birth to four identical quadruplets, clones of each other in other words. Apparently female nine-banded armadillos do this every time.

Gazing into one of the aquarium tanks, I considered the strangeness of the sea anemones. In these photos, there are at least five different species. In the world’s oceans, there are over 1,000 different kinds. For a

Gazing into one of the aquarium tanks, I considered the strangeness of the sea anemones. In these photos, there are at least five different species. In the world’s oceans, there are over 1,000 different kinds. For a mobile species like us, how odd it seems to be non-motile, stuck in one place. Equally curious would be having a body with no head, no back, no front, no rear. Sea anemones have radial symmetry. I wonder what that would feel like?

mobile species like us, how odd it seems to be non-motile, stuck in one place. Equally curious would be having a body with no head, no back, no front, no rear. Sea anemones have radial symmetry. I wonder what that would feel like? The clown fishes which brazenly swim among the anemone’s tentacles represent an interesting ecological relationship known as mutualism. In this type of symbiosis, both animals receive benefit from their association. The fishes, while shielded from being stung by a thick coating of mucus, receive protection from predators. The anemone benefits from the clown fishes’ wastes which fertilize the algae growing symbiotically inside the anemones (a whole other fascinating story of mutualism). Clown fishes may also remove parasites from the anemone or lure prey within reach of the anemone’s tentacles.

The clown fishes which brazenly swim among the anemone’s tentacles represent an interesting ecological relationship known as mutualism. In this type of symbiosis, both animals receive benefit from their association. The fishes, while shielded from being stung by a thick coating of mucus, receive protection from predators. The anemone benefits from the clown fishes’ wastes which fertilize the algae growing symbiotically inside the anemones (a whole other fascinating story of mutualism). Clown fishes may also remove parasites from the anemone or lure prey within reach of the anemone’s tentacles. of life can be centered upon a coral reef. Corals (>6000 species) are animals too. Their bodies resemble tiny sea anemones but are noted for their ability to secrete a

of life can be centered upon a coral reef. Corals (>6000 species) are animals too. Their bodies resemble tiny sea anemones but are noted for their ability to secrete a protective, limestone, exoskeleton. Some, such as brain corals and the mushroom coral are solitary and live in their own small, isolated colonies.

protective, limestone, exoskeleton. Some, such as brain corals and the mushroom coral are solitary and live in their own small, isolated colonies. creatures (>2000 species) have the same radial symmetry, simplicity of body form, and lack of organ systems. But they can move. The mesmerizing pulsating of their “bells” forces out the water within, a practical application of Newton’s Third Law of Motion. Their tentacles also bear stinging nematocyst cells. Some, like the infamous box jellyfish, inject toxins capable of killing a human.

creatures (>2000 species) have the same radial symmetry, simplicity of body form, and lack of organ systems. But they can move. The mesmerizing pulsating of their “bells” forces out the water within, a practical application of Newton’s Third Law of Motion. Their tentacles also bear stinging nematocyst cells. Some, like the infamous box jellyfish, inject toxins capable of killing a human.

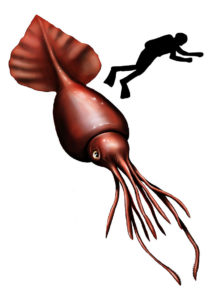

giant squid. Nevertheless, I learned that this animal (of which there are several species) was real and is, in fact, considered the largest invertebrate animal in the world. The giant squid can be over 40 ft. long (mostly tentacle length). The closely related colossal squid is bulkier with a record weight of over half a ton.

giant squid. Nevertheless, I learned that this animal (of which there are several species) was real and is, in fact, considered the largest invertebrate animal in the world. The giant squid can be over 40 ft. long (mostly tentacle length). The closely related colossal squid is bulkier with a record weight of over half a ton.

The octopuses also intrigue me greatly. Zoologists consider them to be the most intelligent of all invertebrates. Cuttlefishes and squids also have large brain to body size ratios, but octopuses are the star pupils. Their brains are said to contain as many neurons as a mouse’s brain.

The octopuses also intrigue me greatly. Zoologists consider them to be the most intelligent of all invertebrates. Cuttlefishes and squids also have large brain to body size ratios, but octopuses are the star pupils. Their brains are said to contain as many neurons as a mouse’s brain.

The beach at Piedras Blancas in coastal California was populated, on the day of my visit, by hundreds of elephant seals. The big bulls were far out to sea so it was females, juvenile males, and young of the year who populated the dark sands. May was molting time for this group and the coats of many resembled a tattered old jacket that should have been discarded long ago. Occasionally a couple of young bulls would begin to feel their oats and a brief barking, shoving, sparring match would ensue. These were but a preview of the fierce, blood-drawing contests in which the big bulls would engage when they returned in late fall. Only the biggest, strongest males could hope to achieve the rank of beach master and be rewarded with the assembling of a harem of 20 to 50 females.

The beach at Piedras Blancas in coastal California was populated, on the day of my visit, by hundreds of elephant seals. The big bulls were far out to sea so it was females, juvenile males, and young of the year who populated the dark sands. May was molting time for this group and the coats of many resembled a tattered old jacket that should have been discarded long ago. Occasionally a couple of young bulls would begin to feel their oats and a brief barking, shoving, sparring match would ensue. These were but a preview of the fierce, blood-drawing contests in which the big bulls would engage when they returned in late fall. Only the biggest, strongest males could hope to achieve the rank of beach master and be rewarded with the assembling of a harem of 20 to 50 females. Blancas, it was common to see their skin marred by the scars of a cookie cutter shark bite. More serious threats to the elephant seals are killer whales and great white sharks. Occasionally one will see a seal bearing a large shark bite mark; the sign of a narrow escape from death.

Blancas, it was common to see their skin marred by the scars of a cookie cutter shark bite. More serious threats to the elephant seals are killer whales and great white sharks. Occasionally one will see a seal bearing a large shark bite mark; the sign of a narrow escape from death. During dives and surfacing, the vibrissae are held back against the face. At depths, while hunting, they are fanned out to better detect any movement of the water molecules. How is this possible? Could I grow my beard and, with closed eyes, hope to detect the passing of a swallow using only the hair of my face? Even though I have learned these research-derived facts about elephant seals, their behavior still seems miraculous. Finding food in the pitch black ocean depths seems an unintelligible, mystical power to me. The cold, the blackness, the vast volume of water to be searched; how amazing their adaptations and survival skills are.

During dives and surfacing, the vibrissae are held back against the face. At depths, while hunting, they are fanned out to better detect any movement of the water molecules. How is this possible? Could I grow my beard and, with closed eyes, hope to detect the passing of a swallow using only the hair of my face? Even though I have learned these research-derived facts about elephant seals, their behavior still seems miraculous. Finding food in the pitch black ocean depths seems an unintelligible, mystical power to me. The cold, the blackness, the vast volume of water to be searched; how amazing their adaptations and survival skills are. What a handsome little creature is the ring-necked snake. Small by serpent standards, they average around ten inches in total length. Their dorsal coloration is a dark, blackish gray with a bright yellow ring around their neck. While their back is somberly colored, much like the pieces of shale under which I often find them, their bellies are a flamboyant yellow or orange.

What a handsome little creature is the ring-necked snake. Small by serpent standards, they average around ten inches in total length. Their dorsal coloration is a dark, blackish gray with a bright yellow ring around their neck. While their back is somberly colored, much like the pieces of shale under which I often find them, their bellies are a flamboyant yellow or orange.

different strategy. Not on the rock-strewn slopes must I search. Instead, it is the small lakes that fill some of the valleys I must investigate. Adult red-spotted newts are aquatic salamanders. Larval newts have gills just as other salamanders and frogs do. But as adults they have lungs. If I lie very quietly at the edge of one of the small ponds on my land, I may be rewarded by seeing a newt lazily float to the surface for a tiny breath of air. If I give myself away, it will very quickly make a U-turn and, with undulations of its oar-like tail, make a crash dive toward the bottom. Introducing oneself to a newt requires patience.

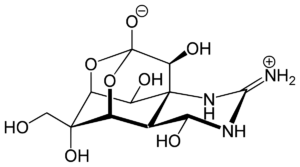

different strategy. Not on the rock-strewn slopes must I search. Instead, it is the small lakes that fill some of the valleys I must investigate. Adult red-spotted newts are aquatic salamanders. Larval newts have gills just as other salamanders and frogs do. But as adults they have lungs. If I lie very quietly at the edge of one of the small ponds on my land, I may be rewarded by seeing a newt lazily float to the surface for a tiny breath of air. If I give myself away, it will very quickly make a U-turn and, with undulations of its oar-like tail, make a crash dive toward the bottom. Introducing oneself to a newt requires patience. Tetrodotoxin is one of the most deadly neurotoxins known. You might be familiar with it as the toxic ingredient in fugu, the Japanese puffer fish delicacy. Tetrodotoxin is found in the bite of the potentially deadly Pacific blue-ringed octopus as well. Who would have thought that our little Hoosier-dwelling newt had anything in common with two of the most notoriously venomous animals in the world?

Tetrodotoxin is one of the most deadly neurotoxins known. You might be familiar with it as the toxic ingredient in fugu, the Japanese puffer fish delicacy. Tetrodotoxin is found in the bite of the potentially deadly Pacific blue-ringed octopus as well. Who would have thought that our little Hoosier-dwelling newt had anything in common with two of the most notoriously venomous animals in the world?

fisherman had drawn up their vessels. Luck was with us. The third fisherman we queried said yes; he would take us out to Pulau Perhentian and come back and pick us up in three days. The negotiated price (to be paid when he came back for us) was 50 Ringgit (about US$23 at that time).

fisherman had drawn up their vessels. Luck was with us. The third fisherman we queried said yes; he would take us out to Pulau Perhentian and come back and pick us up in three days. The negotiated price (to be paid when he came back for us) was 50 Ringgit (about US$23 at that time). water, was a great hammerhead shark many feet in length. The distinctive chocolate-brown back broke the water barely a dozen feet from our boat. As suddenly as it had appeared, the shark was gone. We excitedly congratulated each other’s good fortune in seeing such an extraordinary animal. Inwardly each of us reflected upon the possibility that this fellow might have friends swimming the waters closer to our island destination.

water, was a great hammerhead shark many feet in length. The distinctive chocolate-brown back broke the water barely a dozen feet from our boat. As suddenly as it had appeared, the shark was gone. We excitedly congratulated each other’s good fortune in seeing such an extraordinary animal. Inwardly each of us reflected upon the possibility that this fellow might have friends swimming the waters closer to our island destination.

Stretching before me was a multicolored vista of corals. There were rounded forms of solitary corals like Fungia (looking a bit like a mushroom cap) and the aptly named brain coral with its ridged and furrowed cerebral-like form. There were fan-shaped corals, branching corals like Acropora (staghorn), and corals that were soft instead of stony. Underlying all these were the reef-building corals. Their growth over the millennia had produced the limestone bulwark of the reef. Even now the living polyp animals covering the reef surfaces were working away. Their tentacled, tubular bodies were busily converting carbon, calcium, and oxygen into the stony skeletons we recognize as the reef. One might suppose that all this variety existed in a uniform, concrete-like color but this was not so. Scanning the reef, I could see animals of purple, blue, red, yellow, black, and brown. Each color represented a different species of reef organism. Here and there, embedded in the reef itself, I could see individuals of Tridacna, the giant clam. The reef had

Stretching before me was a multicolored vista of corals. There were rounded forms of solitary corals like Fungia (looking a bit like a mushroom cap) and the aptly named brain coral with its ridged and furrowed cerebral-like form. There were fan-shaped corals, branching corals like Acropora (staghorn), and corals that were soft instead of stony. Underlying all these were the reef-building corals. Their growth over the millennia had produced the limestone bulwark of the reef. Even now the living polyp animals covering the reef surfaces were working away. Their tentacled, tubular bodies were busily converting carbon, calcium, and oxygen into the stony skeletons we recognize as the reef. One might suppose that all this variety existed in a uniform, concrete-like color but this was not so. Scanning the reef, I could see animals of purple, blue, red, yellow, black, and brown. Each color represented a different species of reef organism. Here and there, embedded in the reef itself, I could see individuals of Tridacna, the giant clam. The reef had  literally grown around the larger ones imprisoning them in stone. By periodically opening and closing their shells, they had created a snug space within the reef for themselves. The monstrous clams (the largest ever found weighed over 500 lbs.) lie there with their valves agape filtering water through their mantle cavity in the constant need for freshly oxygenated water and planktonic food.

literally grown around the larger ones imprisoning them in stone. By periodically opening and closing their shells, they had created a snug space within the reef for themselves. The monstrous clams (the largest ever found weighed over 500 lbs.) lie there with their valves agape filtering water through their mantle cavity in the constant need for freshly oxygenated water and planktonic food. caterpillar. Other kinds were nearly two feet in length with tan, spiny skin. All of them crept about on tiny, suction-creating tube feet as they vacuumed up sand and sorted from it the organic detritus which fed them. Arthropods such as shrimp and lobsters prowled the surface of the coral and probed its many crannies in their search for a meal or a secretive hiding spot.

caterpillar. Other kinds were nearly two feet in length with tan, spiny skin. All of them crept about on tiny, suction-creating tube feet as they vacuumed up sand and sorted from it the organic detritus which fed them. Arthropods such as shrimp and lobsters prowled the surface of the coral and probed its many crannies in their search for a meal or a secretive hiding spot. unimagined role of Nemo). These retreated seductively into their sea anemone homes as they attempted to lure me – just another big fish to them – into the poisonous tentacles of the anemones. There were exquisitely colored butterfly fish, their little

unimagined role of Nemo). These retreated seductively into their sea anemone homes as they attempted to lure me – just another big fish to them – into the poisonous tentacles of the anemones. There were exquisitely colored butterfly fish, their little  beak-like snouts probing the corals for algae and plankton. Parrot fish, with their massive teeth exposed in a perpetual smile, cruised over the coral.

beak-like snouts probing the corals for algae and plankton. Parrot fish, with their massive teeth exposed in a perpetual smile, cruised over the coral.

carried out a series of experiments by which he hoped to understand the effects of high population density on the social behavior of rats and mice.

carried out a series of experiments by which he hoped to understand the effects of high population density on the social behavior of rats and mice.

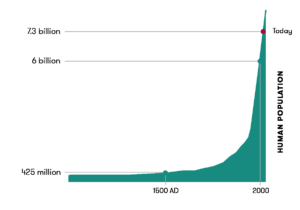

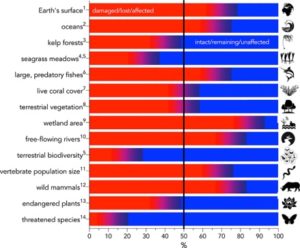

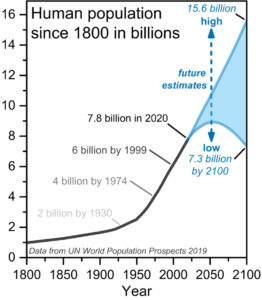

density has increased much over time? It has been estimated that the planet’s human population in 1000 A.D was around 310,000,000. About 47% of earth’s land surface (24,642,757 sq. mi.) is habitable; this is the area that excludes deserts, mountains, etc. (zo.utexas.edu/courses/Thoc/land.html). These figures give us a population density of 12.5 people/sq. mi. at that time. The human population of earth is now around 7,600,000,000. The result is an average population density of 308 people/sq. mi. of habitable land. This is a 2,464% increase in human population density on habitable land over a period of ten centuries. So yes, human population density has increased dramatically over time.

density has increased much over time? It has been estimated that the planet’s human population in 1000 A.D was around 310,000,000. About 47% of earth’s land surface (24,642,757 sq. mi.) is habitable; this is the area that excludes deserts, mountains, etc. (zo.utexas.edu/courses/Thoc/land.html). These figures give us a population density of 12.5 people/sq. mi. at that time. The human population of earth is now around 7,600,000,000. The result is an average population density of 308 people/sq. mi. of habitable land. This is a 2,464% increase in human population density on habitable land over a period of ten centuries. So yes, human population density has increased dramatically over time. many. Research suggests that our human ancestors lived in social groups of around 150 people; as do several hunter-gatherer societies currently (Dunbar, 1992). Dunbar further proposed that when group size exceeds this number, the group becomes unstable and begins to fragment. Dunbar believes that the size of the human neocortex limits the brain’s information processing capacity and this limits the number of relationships an individual can monitor simultaneously. Therefore functional group size is limited to around 150 among primates. Could this mean that the progression toward our own behavioral sink is inevitable simply because we have far exceeded the ideal human global population size (and social structure) thus creating social complexities that our minds are incapable of efficiently processing?

many. Research suggests that our human ancestors lived in social groups of around 150 people; as do several hunter-gatherer societies currently (Dunbar, 1992). Dunbar further proposed that when group size exceeds this number, the group becomes unstable and begins to fragment. Dunbar believes that the size of the human neocortex limits the brain’s information processing capacity and this limits the number of relationships an individual can monitor simultaneously. Therefore functional group size is limited to around 150 among primates. Could this mean that the progression toward our own behavioral sink is inevitable simply because we have far exceeded the ideal human global population size (and social structure) thus creating social complexities that our minds are incapable of efficiently processing? In the meantime, let us recall that less than 500 generations ago all human ancestors were hunter-gatherers whose survival depended upon a deep connection to, an understanding of, and a reverence for the natural world. This relationship is instinctively deep-rooted within us yet. A simple walk in a forest still enthralls us and enhances our mood. How many still enjoy the solitude, scenery, and rewards of our favorite fishing spot, spring mushroom woods, city park, or camping spot? The huge crowds which nowadays surge into our state and national parks offer proof that we still yearn for our ancestral connection to nature. Think about how we are drawn as if magnetically to the ocean surf. Consider our inclination to stand in wonderment as we gaze upon magnificent vistas such as the Tetons, Yosemite Valley, the Grand Canyon, or the Milky Way as it fills the pitch-black, night sky. Yes, in the interim, there are ways to lighten the stresses put upon us by modern human society. There are ways to regain our sanity. They lie just outside our door.

In the meantime, let us recall that less than 500 generations ago all human ancestors were hunter-gatherers whose survival depended upon a deep connection to, an understanding of, and a reverence for the natural world. This relationship is instinctively deep-rooted within us yet. A simple walk in a forest still enthralls us and enhances our mood. How many still enjoy the solitude, scenery, and rewards of our favorite fishing spot, spring mushroom woods, city park, or camping spot? The huge crowds which nowadays surge into our state and national parks offer proof that we still yearn for our ancestral connection to nature. Think about how we are drawn as if magnetically to the ocean surf. Consider our inclination to stand in wonderment as we gaze upon magnificent vistas such as the Tetons, Yosemite Valley, the Grand Canyon, or the Milky Way as it fills the pitch-black, night sky. Yes, in the interim, there are ways to lighten the stresses put upon us by modern human society. There are ways to regain our sanity. They lie just outside our door.

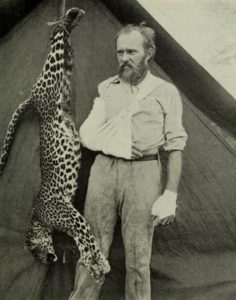

Jones-type adventurer/explorer/big game hunter. Such a story should be expected from a man who killed an attacking leopard with his bare hands. His book is still a fascinating narrative although the recounting of his hunts of charismatic animals, such as elephants and gorillas, will trouble many readers.

Jones-type adventurer/explorer/big game hunter. Such a story should be expected from a man who killed an attacking leopard with his bare hands. His book is still a fascinating narrative although the recounting of his hunts of charismatic animals, such as elephants and gorillas, will trouble many readers. But back to the story; it was during one hunt in Africa that Akeley himself learned just how quietly and craftily an elephant can approach a pursuer. Hunting for museum specimens, he was stalking a group of three bulls. Akeley at last heard the crashing sounds of feeding coming from a bamboo forest 200 yards ahead. Pausing to appraise the rifle and cartridges his gun-bearer had handed him, Akeley: was suddenly conscious that an elephant was almost on top of me. I have no knowledge of how the warning came. I have no mental record of hearing him, seeing him, or of any warning from the gun boy. . . My next mental record is of a tusk right at my chest. Akeley instinctively grabbed the tusk and swung in between the two. This he had practiced in his mind in anticipation of such an attack and he believed this “rehearsing” is what saved his life.

But back to the story; it was during one hunt in Africa that Akeley himself learned just how quietly and craftily an elephant can approach a pursuer. Hunting for museum specimens, he was stalking a group of three bulls. Akeley at last heard the crashing sounds of feeding coming from a bamboo forest 200 yards ahead. Pausing to appraise the rifle and cartridges his gun-bearer had handed him, Akeley: was suddenly conscious that an elephant was almost on top of me. I have no knowledge of how the warning came. I have no mental record of hearing him, seeing him, or of any warning from the gun boy. . . My next mental record is of a tusk right at my chest. Akeley instinctively grabbed the tusk and swung in between the two. This he had practiced in his mind in anticipation of such an attack and he believed this “rehearsing” is what saved his life. which the presenter spoke about the use of Asian elephants in the logging industry in Thailand. One particular slide stuck in my mind. It showed a male under restraint (one leg chained to a tree) because he was in musth. Musth is the male elephant’s equivalent to the female heat cycle. During musth, the testosterone levels of the male become elevated many fold. The temporal glands on each side of the head produce pheromones which dampen the side of the bull’s head. Additional they tend to produce a constant stream of urine which wets their hind legs and thus marks the path of their wonderings. Woe to a younger, weaker male who crosses this track.

which the presenter spoke about the use of Asian elephants in the logging industry in Thailand. One particular slide stuck in my mind. It showed a male under restraint (one leg chained to a tree) because he was in musth. Musth is the male elephant’s equivalent to the female heat cycle. During musth, the testosterone levels of the male become elevated many fold. The temporal glands on each side of the head produce pheromones which dampen the side of the bull’s head. Additional they tend to produce a constant stream of urine which wets their hind legs and thus marks the path of their wonderings. Woe to a younger, weaker male who crosses this track. saw many elephants. How exciting to finally get to see these fascinating creatures up close as they browsed, tended their young, enjoyed a dust bat, or simply rested in the shade of an immense sausage tree. Here I experienced firsthand the storied silence with which they can move.

saw many elephants. How exciting to finally get to see these fascinating creatures up close as they browsed, tended their young, enjoyed a dust bat, or simply rested in the shade of an immense sausage tree. Here I experienced firsthand the storied silence with which they can move. glanced to the right, a young male elephant walked by our vehicle. Although this four-ton animal was within a few yards of the Land Rover, not a hint of the sound of footfall could I detect. It was abruptly very clear to me how one could be focused upon something else, as Akeley had been, and have one of these huge animals stealthily and suddenly materialize upon you. Quite an eye-opening experience it was.

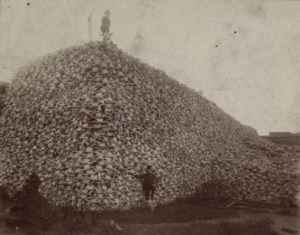

glanced to the right, a young male elephant walked by our vehicle. Although this four-ton animal was within a few yards of the Land Rover, not a hint of the sound of footfall could I detect. It was abruptly very clear to me how one could be focused upon something else, as Akeley had been, and have one of these huge animals stealthily and suddenly materialize upon you. Quite an eye-opening experience it was. I chose The Silence of Elephants as the title for this composition for another reason too. Not hearing elephants is now more often due to the simple fact that their numbers have been so drastically reduced. This is true in both Asia and Africa. As an example, when we finally reached Tarangire N.P., we had our best success seeing elephants, over 100 in a couple of days’ time. But Akeley, in his aforementioned book, reported seeing 700 elephants in just one, single herd. This was in the early 1900’s

I chose The Silence of Elephants as the title for this composition for another reason too. Not hearing elephants is now more often due to the simple fact that their numbers have been so drastically reduced. This is true in both Asia and Africa. As an example, when we finally reached Tarangire N.P., we had our best success seeing elephants, over 100 in a couple of days’ time. But Akeley, in his aforementioned book, reported seeing 700 elephants in just one, single herd. This was in the early 1900’s without them. As researchers have come to know more about them, the argument against killing elephants has grown stronger. We now know that there is much going on within that big brain of theirs, the largest of any land mammal.

without them. As researchers have come to know more about them, the argument against killing elephants has grown stronger. We now know that there is much going on within that big brain of theirs, the largest of any land mammal.

Heavea brasiliensis trees. Each tree bore the familiar, sloping, parallel grooves of the rubber tapper’s awl. A small cup rested upon each trunk, ready to capture the dripping latex spawned by the tapper’s delicate gouging of the bark. Plantations such as these made Malaysia one of the world’s top exporters of natural rubber. Down the valley, interspersed between palm and rubber, were sprinkled the kampong houses of the Malay rice growers. These houses,

Heavea brasiliensis trees. Each tree bore the familiar, sloping, parallel grooves of the rubber tapper’s awl. A small cup rested upon each trunk, ready to capture the dripping latex spawned by the tapper’s delicate gouging of the bark. Plantations such as these made Malaysia one of the world’s top exporters of natural rubber. Down the valley, interspersed between palm and rubber, were sprinkled the kampong houses of the Malay rice growers. These houses, beautiful in their rustic simplicity, stood above the ground on stilts. Not only did this keep the home above a potential flood, such a design made entry rather more difficult for unwelcome house guests such as scorpions, centipedes, and Indian cobras. Built above the ground, the homes were also more likely to catch cooling breezes. In a home with no electricity, this is no small matter. After all this is a land where the daily temperature hovers in the mid-nineties and the humidity approaches one hundred percent. The houses often featured a high-pitched roof covered by attap palm thatch. This design rapidly shed the rain and allowed hot air to rise above the floor-level living spaces. All in all, the houses’ clever designs gave a distinct quality of bucolic beauty, minimalism, and comfort.

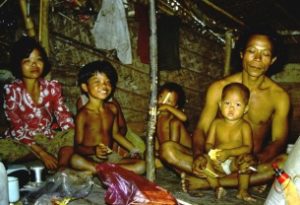

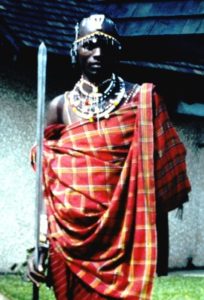

beautiful in their rustic simplicity, stood above the ground on stilts. Not only did this keep the home above a potential flood, such a design made entry rather more difficult for unwelcome house guests such as scorpions, centipedes, and Indian cobras. Built above the ground, the homes were also more likely to catch cooling breezes. In a home with no electricity, this is no small matter. After all this is a land where the daily temperature hovers in the mid-nineties and the humidity approaches one hundred percent. The houses often featured a high-pitched roof covered by attap palm thatch. This design rapidly shed the rain and allowed hot air to rise above the floor-level living spaces. All in all, the houses’ clever designs gave a distinct quality of bucolic beauty, minimalism, and comfort. those who would view the valley only from the road. This secreted realm concealed a tiny village inhabited by Temuan aborigines. It was a piece of the world which clearly conveyed to me the realization that I was in a realm totally alien to anything I had previously experienced. It was a microcosmic piece of planet earth totally foreign to me in every way. The language, methods of procuring food, mode of dress, habits of hygiene, and spiritual beliefs of the Temuan were all utterly novel to me.

those who would view the valley only from the road. This secreted realm concealed a tiny village inhabited by Temuan aborigines. It was a piece of the world which clearly conveyed to me the realization that I was in a realm totally alien to anything I had previously experienced. It was a microcosmic piece of planet earth totally foreign to me in every way. The language, methods of procuring food, mode of dress, habits of hygiene, and spiritual beliefs of the Temuan were all utterly novel to me. half feet in height; the women closer to five feet. Their small stature was an expression of Bergmann’s Rule. This zoological principle holds that mammals (humans included) which live in the tropics tend to have smaller bodies than those that live at higher latitudes. This is because smaller mammals, somewhat counter-intuitively, have more surface (skin) area in relationship to body volume than larger ones. Having greater surface area allows for more efficient radiation of body heat and thus a greater ability to stay cool in the tropical heat. I can attest to the efficacy of this body form. On multiple hikes, I would find myself wearing sweat-soaked clothing so wet it looked as if I had fallen into a stream. Meanwhile, the skin of my Temuan companions always seemed to stay amazingly dry. Several thousand years of natural selection can work its adaptive genius on humans just as well as any other species.

half feet in height; the women closer to five feet. Their small stature was an expression of Bergmann’s Rule. This zoological principle holds that mammals (humans included) which live in the tropics tend to have smaller bodies than those that live at higher latitudes. This is because smaller mammals, somewhat counter-intuitively, have more surface (skin) area in relationship to body volume than larger ones. Having greater surface area allows for more efficient radiation of body heat and thus a greater ability to stay cool in the tropical heat. I can attest to the efficacy of this body form. On multiple hikes, I would find myself wearing sweat-soaked clothing so wet it looked as if I had fallen into a stream. Meanwhile, the skin of my Temuan companions always seemed to stay amazingly dry. Several thousand years of natural selection can work its adaptive genius on humans just as well as any other species. their village until three years later, when I had to bid them a reluctant adieu, they were ever gracious and accepting of my presence among them. Their skills in traversing the forest were unparalleled. How, I wondered, did they avoid becoming disoriented and lost in this vast, green world? To my eye, the forest appeared uniform in every direction I looked; dangerously so for a solo novice. I once asked them how they accomplished their amazing navigation. Their answer, while patently obvious to them, did little to illuminate this uncanny ability for me. “We just know where to go,“ was their cryptic explanation of this incredible orienteering ability.

their village until three years later, when I had to bid them a reluctant adieu, they were ever gracious and accepting of my presence among them. Their skills in traversing the forest were unparalleled. How, I wondered, did they avoid becoming disoriented and lost in this vast, green world? To my eye, the forest appeared uniform in every direction I looked; dangerously so for a solo novice. I once asked them how they accomplished their amazing navigation. Their answer, while patently obvious to them, did little to illuminate this uncanny ability for me. “We just know where to go,“ was their cryptic explanation of this incredible orienteering ability. cup he had fashioned from a section of giant bamboo. The skillfulness with which the Temuan were able to manipulate objects in their environment into articles of utilitarian use simply defied imagination. Never before had I encountered a people so connected, so resourceful, so intimately coupled with the natural world.

cup he had fashioned from a section of giant bamboo. The skillfulness with which the Temuan were able to manipulate objects in their environment into articles of utilitarian use simply defied imagination. Never before had I encountered a people so connected, so resourceful, so intimately coupled with the natural world. trackers, hunters, herbalists, and story-tellers atrophied. Caught in limbo between the old way of life and Malaysia’s rapid ascension into the modern world of commerce, the younger generation of Temuan was not adept at either. Ten thousand years as slash and burn agrarians and hunter-gatherers leave one ill prepared for a job in the contemporary world. Starting work at 7:00A sharp means little to a people who have never had a clock. The eight hour shift is incomprehensible to a people who have for millennia eaten, slept, hunted, and socialized in accord with rhythms not of the clock but of the corpus and the forest. Dodong had no need for literacy to fully understand all this. His innate intelligence and sense of place told him all he needed to know.

trackers, hunters, herbalists, and story-tellers atrophied. Caught in limbo between the old way of life and Malaysia’s rapid ascension into the modern world of commerce, the younger generation of Temuan was not adept at either. Ten thousand years as slash and burn agrarians and hunter-gatherers leave one ill prepared for a job in the contemporary world. Starting work at 7:00A sharp means little to a people who have never had a clock. The eight hour shift is incomprehensible to a people who have for millennia eaten, slept, hunted, and socialized in accord with rhythms not of the clock but of the corpus and the forest. Dodong had no need for literacy to fully understand all this. His innate intelligence and sense of place told him all he needed to know. wood fire; eating snakes, monkeys, or insects; dying from an infection easily cured by an antibiotic they say. Doubtless there is merit to their argument. Who am I to say that the forest may be a better home than one with plumbing and electricity? What privilege have I to suggest the young Temuan shouldn’t have at least a chance to wear Nike® running shoes, own a smart phone, watch television, or clad themselves in Outerwear® when these things are readily available to me? I have no reasoned answer as to why my aboriginal friends are not equally entitled to have more.