A few years ago, I was doing some volunteer work in the Department of Biology at Indiana State University. My job entailed preparation of mammal museum specimens. So it was that a couple of road-killed armadillos came my way. I had dealt with their preparation before and, in all honesty, I looked forward to working on these two without eagerness. Preparing an armadillo specimen is a little too much like work. Their name means “little armored one”, which might give insight into my lack of enthusiasm.

I was however intrigued by the locations where they were collected. These were not, as you might expect, from Texas or Alabama but from right here in Indiana. They were killed on roads in the southern part of the state near the Ohio River. Back then I was unaware that armadillos even occurred in the state. Not surprising since, at that time, only three specimens of Dasypus novemcinctus had been referred to ISU. But now, just a few short years later, there are over 80 records of these unique little mammals from around the state. They’ve even made it to Porter County way up on Lake Michigan.

Armadillos are native to South America. In fact, on that continent, there are something like twenty different species of such animals. They vary in size. The smallest is the six-inch-long pink fairy armadillo. These little fellows are found in Argentina.

something like twenty different species of such animals. They vary in size. The smallest is the six-inch-long pink fairy armadillo. These little fellows are found in Argentina.

At the other extreme is the giant armadillo which reaches a length of three feet and weighs over seventy pounds. This species has a wide range and is found in several South American countries including Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru.

At the other extreme is the giant armadillo which reaches a length of three feet and weighs over seventy pounds. This species has a wide range and is found in several South American countries including Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru.

The nine-banded armadillo is intermediate in size between these two. Its length and weight are comparable to a cat or small dog. Surprisingly enough, there was another armadillo that lived in Indiana long, long ago. Known as the beautiful armadillo, this species was much larger than its nine-banded cousin with a length of around four feet and a weight of forty pounds or so. The beautiful armadillo became extinct several thousand years ago.

So why are we finding armadillos in Indiana now? The simplest answer is that animals, as their population increases, instinctively seek to disperse into suitable new habitats. This reduces competition within the population, lessens inbreeding, and allows them to colonize new areas.

The nine-banded armadillo didn’t make it to the United States until the late 1800’s. First appearing in Texas, they then gradually invaded new territory to the east. By 1940 they were seen in Alabama. Prior to that, they had jumped to Florida courtesy of human release. By the 1950’s they had spread throughout that state.

Here in Indiana, we’ve recently seen our own examples of the tendency for young animals to venture afar as they seek new territory. In 2003, a young gray wolf was found dead in the northern part of the state. This species was extirpated from Indiana by 1908. The 2003 animal was later determined to have come from Wisconsin.

As a viable population, the mountain lion was gone from Indiana by the late 1800’s. But, in 2009 and 2010, confirmed sightings of a mountain lion were made in Clay and Greene County respectively. In 2011, a male mountain lion was killed on a roadway in Connecticut. Evidence pinpointed the origin of this animal as the Black Hills of South Dakota, 1500 miles away.

A 2004 article in the Bloomington Herald Times recounts the journey of a bobcat radio-collared in Greene County. The animal ended up injured on a road in Michigan, 294 miles away. So, as you can see, animals can be amazingly long-distance travelers.

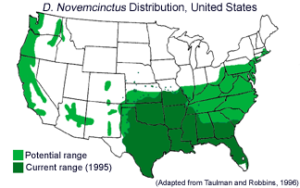

How far will armadillos expand their range? According to the website Armadillo Online, cold winter temperatures and annual rainfall (at least 15 in./year needed) are major factors limiting distribution. The website features a 1995 map of the potential range expansion for the nine-banded armadillo. Note that Porter County, Indiana is already farther north than then predicted.

How far will armadillos expand their range? According to the website Armadillo Online, cold winter temperatures and annual rainfall (at least 15 in./year needed) are major factors limiting distribution. The website features a 1995 map of the potential range expansion for the nine-banded armadillo. Note that Porter County, Indiana is already farther north than then predicted.

I have yet to see an armadillo meandering through my rural Indiana property. I scan each morning with hope, but so far without reward. But I also must consider the possibility that a new guest might be less welcome than I imagine. Armadillos are diggers and burrowers; not sure what Anne would think should one turn its attention to her diligently tended flower beds. But I can’t help myself, I just find them fascinating.

So, for the time being, I must be content with the occasional armadillo encounter while wintering on the Nature Coast of western Florida. Although primarily nocturnal, I do see them there during the day. Invariably they are fixated on industriously nosing their way through the surface litter. A keen sense of smell is their major asset in the search for food. Thus engaged, one can quietly walk right up to them. Armadillos have tiny, peg-like teeth so most of their diet consists of small animals such as beetles, caterpillars, ants, spiders, and centipedes. Fruits such as wild grape are sometimes eaten as well as certain soil fungi. They wouldn’t be fussy about consuming a small vertebrate, such as a frog, or snacking on bird eggs if they were to encounter them.

One aspect of armadillo biology that really puzzles me is their reproductive physiology. The zygote, or fertilized egg, undergoes fission to form four identical cells. This is not unusual. That’s the way our early embryological development begins too. But, in armadillos, each of these four cells then goes on to independently develop into a fetus. Thereafter (about four months) the female gives birth to four identical quadruplets, clones of each other in other words. Apparently female nine-banded armadillos do this every time.

identical cells. This is not unusual. That’s the way our early embryological development begins too. But, in armadillos, each of these four cells then goes on to independently develop into a fetus. Thereafter (about four months) the female gives birth to four identical quadruplets, clones of each other in other words. Apparently female nine-banded armadillos do this every time.

Biologically this doesn’t seem like a good idea. Having offspring which are genetically different from each other is the normal pattern. Such variation bestows adaptability for animals, increasing the odds that at least some can cope with and survive varying environmental conditions.

But hold on! Recent research suggests that the quads are not as identical as they may appear. Just as in human identical twins, some slight differences do occur. Preliminary research indicates such dissimilarities are due to developmental variations regarding which genes are activated. Perhaps armadillo youngsters aren’t “rubber-stamped” look-alikes as we have thought. Stay tuned.

Unfortunately, your best chance of seeing an armadillo here in southwestern Indiana is as a roadkill. A couple of factors make this likely. Being nocturnal can put them on roadways at night when they are difficult to spot. Armadillos also have a curious reaction to being frightened; they tend to leap upward. You can see examples of this on YouTube (armadillo jump – YouTube).

In the wild, this alarmed leap might momentarily startle a predator, such as a coyote or bobcat, allowing the armadillo to run for it. However, it is an extremely poor strategy when confronted by an automobile. Such a jump practically ensures that they are going to be hit by the front or the undercarriage of the vehicle. Sometimes behaviors that are useful in nature don’t transfer well to the human-dominated world.

So, be on the lookout. It looks like armadillos are here to stay for awhile. And what an intriguing little creature they are. Ever expanding their range, armadillos crossed the Panamanian Land Bridge and entered North America some three million years ago. Surely such an ancient history is worthy of some degree of respect.

People are often prone to ask, “What good is it”, when discussion of some particular animal arises. Nine-banded armadillos do have certain practical values. The insects they eat may be harmful to humans in one way or another. People have, and do, use them as a food source. Armadillos are also used for medical research purposes. Scientists may use them to learn more about the genetics and embryology of multiple births and twinning. Nine-banded armadillos, like humans, may also carry the bacterium responsible for leprosy. Thus, they serve as source of research data on the effects and treatment of this disease.

But my belief is that the “what good” question is a poor one. Each organism plays some role within its ecosystem, though we may not yet fully understand this function. Each species is a unique conception, the result of adaptation and endurance over immense lengths of time. Being a product of the Creation, seems reason enough to give them space, allow them to do what they do, to direct admiration toward their uniqueness and survival skills. Each such species should remind us that we live in a world of wonder. We are surrounded by an incredibly fascinating richness of life here on our only home. Here on this, our Pale Blue Dot.

Photo Credits:

Heading photo by the author. Pink fairy armadillo by: Cliff at commons.wikimedia.org (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) Range map at: Armadillo Expansion (armadillo-online.org) Armadillo with litter: Armadillos: Identical Quadruplets Every Time (carnegiemnh.org) Additional Information:

DNR: Fish & Wildlife: Armadillo (in.gov)

Armadillo Online! (armadillo-online.org)