Part 2: Happy Birthday Ancient Earth

What then of the age of the earth? Where, within his religion, may my pupil have gotten the idea that the earth is quite young geologically? Does the Bible in fact state that the earth is a relatively young; perhaps only a few thousand years old? Actually, it does not specifically do so. Some scholars have assumed the genealogies of biblical patriarchs to be historically correct. They have then used these lineages to roughly estimate the passage of time since the earth’s creation. In fact, there is an exceedingly long  history of attempts to use the Bible to do just that. If one peruses the Internet searching for references to young earth creationism, one will find dozens of mentions of authors who have done so. Such efforts began as early as the second century B.C. and continued at least into the nineteenth century. Estimates of earth’s age based upon various translations of the Bible vary. The date of creation based on the Septuagint is said to be 5500 BC. Using the Samaritan Pentateuch, it is around 4300 BC, and relying upon the Masoretic texts yields a date of 4000 BC. Thus we can see many possible sources in regards to how a scripturally based belief in a six to eight thousand year old earth could have arisen.

history of attempts to use the Bible to do just that. If one peruses the Internet searching for references to young earth creationism, one will find dozens of mentions of authors who have done so. Such efforts began as early as the second century B.C. and continued at least into the nineteenth century. Estimates of earth’s age based upon various translations of the Bible vary. The date of creation based on the Septuagint is said to be 5500 BC. Using the Samaritan Pentateuch, it is around 4300 BC, and relying upon the Masoretic texts yields a date of 4000 BC. Thus we can see many possible sources in regards to how a scripturally based belief in a six to eight thousand year old earth could have arisen.

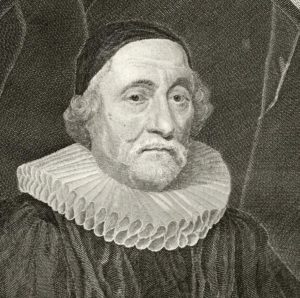

However, I have often found that the quest to more rationally or systematically explain the basis for the belief in an earth only a few thousand years of age often leads to one man – James Ussher. Ussher (1581-1656) was the Anglican Church of Ireland’s Archbishop of Armagh. I must admit to a general tendency to be suspicious of pronouncements of fact from scholars working nearly five hundred years ago. It simply seems reasonable to me to accept the idea that we have made great progress, during the last five centuries, in understanding the workings of the physical and biological world in which we live. As an example, I think most of us, if afflicted with serious disease, would rather go to a 21st century doctor rather than a medieval barber-physician whose first diagnosis might call for a good blood-letting via the application of leeches. Thus, I’ve always been more than skeptical of Ussher’s assertions regarding the age of the earth.

However, I have often found that the quest to more rationally or systematically explain the basis for the belief in an earth only a few thousand years of age often leads to one man – James Ussher. Ussher (1581-1656) was the Anglican Church of Ireland’s Archbishop of Armagh. I must admit to a general tendency to be suspicious of pronouncements of fact from scholars working nearly five hundred years ago. It simply seems reasonable to me to accept the idea that we have made great progress, during the last five centuries, in understanding the workings of the physical and biological world in which we live. As an example, I think most of us, if afflicted with serious disease, would rather go to a 21st century doctor rather than a medieval barber-physician whose first diagnosis might call for a good blood-letting via the application of leeches. Thus, I’ve always been more than skeptical of Ussher’s assertions regarding the age of the earth.

But wait just a darned minute you might argue. Why do we have to jettison scholarly work simply because it was done in the 16th century? What about  Copernicus? Didn’t he figure out the heliocentric motion of the planets back in the 1500’s? Didn’t Isaac Newton propose the laws explaining the motion of objects not long after this? What about Galileo Galilei? Didn’t he build a telescope and make the first observations of the moons of Jupiter in the early 17th century? I would have to say yes, all of this is true. I would never dare to suggest that

Copernicus? Didn’t he figure out the heliocentric motion of the planets back in the 1500’s? Didn’t Isaac Newton propose the laws explaining the motion of objects not long after this? What about Galileo Galilei? Didn’t he build a telescope and make the first observations of the moons of Jupiter in the early 17th century? I would have to say yes, all of this is true. I would never dare to suggest that  many of the scholars at work during those time periods did not possess true genius. In fact, and this may surprise you, the more I have learned about James Ussher the more I appreciate his work. I simply think that he made some questionable assumptions in trying to precisely date the origin of the earth. It is true that both history and science have proven his 6000 year old earth incorrect; but there is still a bit more about James Ussher that merits consideration.

many of the scholars at work during those time periods did not possess true genius. In fact, and this may surprise you, the more I have learned about James Ussher the more I appreciate his work. I simply think that he made some questionable assumptions in trying to precisely date the origin of the earth. It is true that both history and science have proven his 6000 year old earth incorrect; but there is still a bit more about James Ussher that merits consideration.

Brooding upon the rejection of my teaching of the plate tectonics theory, I wanted to know a little more about Archbishop Ussher myself. By all accounts, James Ussher was a man of extreme intelligence. He entered Trinity College in Dublin at age thirteen. At age seventeen, he acquired a bachelor’s degree. He was ordained in the church at twenty-one and by the time he was in his late twenties had become a professor at Trinity College. He was said to be gifted in languages and, during his lifetime, amassed a personal library containing thousands of volumes. His scholarship would be difficult to deny.

The issue that pertains to my discussion, the date of the origin of earth, is presented in Ussher’s 1650 publication of a dissertation entitled Annales veteris testament, a prima mundi origine deducti or, in English, Annals of the Old Testament, deduced from the first origins of the world. This classic work is still available as an English translation from the Latin. In it, Ussher offers a comprehensive historical record of the early world from the creation to 70 AD. However, Ussher’s chronology of the earth’s history, including the date of the origin of life, has been characterized by scientists as wholly inaccurate.

I must admit that as a result of a rather lengthy training in the biological and geological sciences, I had considered Ussher’s work to be of little significance. However, as I tried to learn more about him, I ran across an article that made me reassess my opinion. In 1991 the late Stephen J. Gould, writing in Natural History magazine, suggested that perhaps we should not be so disdainful of Ussher’s endeavor. Gould pointed out that, given the primitive state of science, such attempts to use the Bible and other ancient texts to deduce the age of the earth’s origins was a common scholastic endeavor. In other words, given the lack of the tools and information we now have at our disposal – such as an increased understanding of stratigraphy, a more complete fossil record, knowledge of radioactivity, the development of radiometric dating techniques, and improved dendrochronological data – how else might academics attack the problem of determining the earth’s history? Other intellectuals of the time (e.g. Johannes Kepler, John Lightfoot, Isaac Newton), who worked on timelines for the earth were trying to do more than just determine the date of  creation. In reality, they were attempting to establish a comprehensive chronology of the earth’s history and its historic events by using the Bible and other classical works. In his essay, Fall in the House of Ussher, Gould remarks that perusal of the “Annals of the Old Testament” reveals that only about seventeen percent of the work is biblical. Ussher’s book is available now on the popular Internet site Amazon.com under the title The Annals of the World. I found one reviewer’s comments telling. As if to support Gould’s observation that the book actually contained little biblical material, the reader stated that he assumed the book would give him additional insight into biblical history. It did not; in fact he reported it gave him little specific information about events in the Bible.

creation. In reality, they were attempting to establish a comprehensive chronology of the earth’s history and its historic events by using the Bible and other classical works. In his essay, Fall in the House of Ussher, Gould remarks that perusal of the “Annals of the Old Testament” reveals that only about seventeen percent of the work is biblical. Ussher’s book is available now on the popular Internet site Amazon.com under the title The Annals of the World. I found one reviewer’s comments telling. As if to support Gould’s observation that the book actually contained little biblical material, the reader stated that he assumed the book would give him additional insight into biblical history. It did not; in fact he reported it gave him little specific information about events in the Bible.

So there you have it. A strong argument could be made for cutting Archbishop Ussher (and other biblical chronologists) a little slack in regards to his now much maligned date of creation. For the period, he was doing what we may think of as highly advanced academic research. The date Ussher established for the beginning of creation was, by the way, quite specific. It was Sunday Oct. 23, 4004 B.C.

In order to pinpoint the date of creation, Ussher had to make several rather questionable subjective assumptions. These are well described in Catherine Baker’s The Evolution Dialogs: Science, Christianity and the Quest for  Understanding. For example, Ussher reasoned that the creation occurred in autumn since this is a time for the ripening of the fruits of trees. As Adam and Eve were tempted with the eating of such a fruit, the first humans must have been created in the fall season. Ussher also inferred that the creation must have occurred at some significant astronomical period such as equinox or solstice. It was certainly a monumental event; therefore it must have occurred at a noteworthy time he reasoned. Referring to astronomical tables, Ussher found that the nearest Sunday proximate to the equinox in 4004 B.C. was Sunday, Oct. 23rd. The creation actually began, he believed, on the evening of the previous day.

Understanding. For example, Ussher reasoned that the creation occurred in autumn since this is a time for the ripening of the fruits of trees. As Adam and Eve were tempted with the eating of such a fruit, the first humans must have been created in the fall season. Ussher also inferred that the creation must have occurred at some significant astronomical period such as equinox or solstice. It was certainly a monumental event; therefore it must have occurred at a noteworthy time he reasoned. Referring to astronomical tables, Ussher found that the nearest Sunday proximate to the equinox in 4004 B.C. was Sunday, Oct. 23rd. The creation actually began, he believed, on the evening of the previous day.

Some have also suggested that the date Ussher imagined might have fed upon his preconceived notion of how old the earth should be. For example, certain biblical passages used by early chronologists (such as 2 Peter 3:8 and Psalms 90:4) suggested to them that a thousand years were but a day to God. In other words, a six day creation could represent an earth of around 6000 years in age. This would fit well if, like Ussher, one was working under the assumption that the Bible was literally correct in every respect.

Much material is available relative to the manner in which Ussher developed his historical chronology. It is voluminous and detailed; I will leave that for you to pursue or not. My point is that Ussher was doing the best he could with the implements at hand. Since Ussher perceived the Bible as historical, he merged information in it with that of other significant written resources: Egyptian, Persian, Greek and Roman histories for example. As a non-scientist in a pre-scientific world, his efforts produced a product that seemed eminently reasonable for the period.

But that’s just it: for the period. We are talking about the 17th-19th centuries. Why must we continue to accept the work of Ussher, and other such chronologists, as definitive? Why must we use it as a basis, as my fledgling science student did, for rejecting much of the physical knowledge of the earth that we have gained in the past several hundred years? Apparently, for many Christian conservatives, there is a belief that the Bible does indeed specifically state that the earth is 6000 years old. Perhaps the reason that Ussher’s timeline persists as reasonable in the mind of these folks is that, beginning shortly after the publication of his Annals, Ussher’s chronological timeline was printed in the margins of certain bibles. “Up until fairly recently, nearly all printings of the King James Bible included dates in the marginal notes which helped place Biblical events in their chronological context” (from the website of the Institute for Creation Research). I suspect that Ussher’s chronology has thus acquired great power of persuasion through its association with the scriptures. As a result, in the eyes of many, his chronology literally took on the authority of God. Perhaps for some people, to believe otherwise is to open a chink in the armor of their assumed biblical inerrancy. Accepting that the earth is ancient beyond understanding might put one on an oily incline. The next thing you know people will be arguing that nothing in the Bible is true. This, I presume, is the great fear.

It is a fine ethical line one walks as a biology teacher when dealing with student beliefs. I have often wondered whether or not I should have expressed to my doubting student the sadness I experienced. It was a dejection caused by their belief that they had to make a definitive, final choice between science and religion. For you see in my mind, the spectacle and stupendous power of earth’s geologic forces are worthy of awe as well. My understandings of the forces which propel the tectonic plates over the surface of our world fill me with appreciation for the powerful dynamics at work within the cosmos. I feel small and insignificant. I am humbled and put into my place in the scheme of things. The natural is no less than the supernatural, quite capable of generating wonder and reverence.

Then again if I had articulated these ideas to my student, perhaps they would have felt sadness for me; a worshipper of geologic forces instead of a God. But, in reality, I’m not sure we stood so far apart. As a religious naturalist, I accept the belief that there is a creative force responsible for our world and the universe in which we dwell. There is a Force – awesome, mysterious, and unfathomable – which has, over the past fourteen billion years, created a universe and an earth which has become ever more complex and biodiverse. This Force has also created an organism with remarkable inquisitiveness, inventiveness, and intelligence. It is us.

And so the melancholy I felt in my classroom those many years ago stemmed from the following notion. There is no need to cling to ancient  philosophies fearing that, if we do not, our beliefs are lost. Just as we evolve biologically, we should evolve culturally as well. We humans test and probe and seek and discover. In the discovery we march forward, gaining an ever-increasing understanding of the world around us. Coming to understand that the earth is not thousands but billions of years old should not frighten us. This knowledge should not be seen as a wedge that will somehow separate us from a desire for communion with the Creator. It would be a capricious deity who gave us the mental gifts necessary to explore the universe and then slapped us for using these talents.

philosophies fearing that, if we do not, our beliefs are lost. Just as we evolve biologically, we should evolve culturally as well. We humans test and probe and seek and discover. In the discovery we march forward, gaining an ever-increasing understanding of the world around us. Coming to understand that the earth is not thousands but billions of years old should not frighten us. This knowledge should not be seen as a wedge that will somehow separate us from a desire for communion with the Creator. It would be a capricious deity who gave us the mental gifts necessary to explore the universe and then slapped us for using these talents.

All this is not to say that we must jettison the wisdom gained by the Ancients, wisdom which is often set down in religious scriptures. There are primal spiritual truths which we, the human race, should grasp firmly and take along with us as we march forward. My wish would be that my student comes to understand that these truths are not dependent upon whether biblical genealogies are historical are not. The ancient authors of scripture were trying to answer the same questions that baffle us now even now. How did we get here? What should be the purpose of our lives? Why are our lives so ephemeral and so often fraught with difficulties? How should we interact with our fellow humans?

In their asking, our far-distant ancestors discovered truths of much greater import than the age of the earth. We should acknowledge and hold tightly these momentous transcendent verities. There was a moment of creation. Even if not supreme, we are a remarkable and special component of that Creation. We need to rely on each other. We must exercise care of our natural world. There is a powerful creative force at work in the cosmos.

As we move onward, we surely must not fear to interpret our ancient spiritual truths in the light of new knowledge. If we were to do this, my incredulous student could rightly acknowledge that the good bishop did admirable work for his day. But my youthful protégé could also appreciate how the mighty Cascades have reared their lovely crowns. He might better understand why the earth beneath his feet may sometimes tremble.

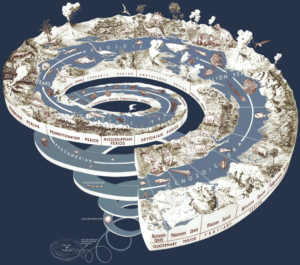

Photo Credits: earth from Apollo 17 - commons.wikimedia.org Roman Septuagint (1587) - commons.wikimedia.org Archbishop James Ussher by J. Houbraken at commons.wikimedia.org Coepernicus title page (1543) - commons.wikimedia.org Galileo Galilei by Justin Sustermans at commons.wikimedia.org The Annals of the World at www.amazon.com The Evolution Dialogues at www.amazon.com Book of Genesis text by the author geologic time spiral by USGS at commons.wikimedia.org Cascade range at www.WA.gov