Having been married to a field biologist for many years, my wife Anne has become remarkably accommodating when it comes to some of my idiosyncrasies. One of these eccentricities, as I suppose most people would describe it, has been my penchant for lugging home all manner of strange specimens inanimate, living, and deceased. As I recall, it began with my

first forays into biological research during undergraduate school. First there were the little glass vials containing the stomachs of white-footed and deer mice. Analysis of their contents needed to be made in order to determine the little rodents’ food habits. Then there were the jars of freshwater fishes needing identification for my class in vertebrate zoology. An occasional road-killed squirrel or fox demanding examination came to be expected by my patient and cooperative spouse

Often my specimens required preservation until I could get to them. Again, Anne calmly watched as sandwich bags containing short-tailed shrews, jumping mice, and prairie voles were stored in our freezer. Still, I would occasionally detect a transitory look from her that suggested my activities were straying far outside the bounds of what constituted normal human behavior. Such a look would cause me to wonder if she was harboring the same thought as the unfrozen caveman lawyer character played by the late Phil Hartman. “Your world is strange to me”, he would intone to bystanders during one of his Saturday Night Live skits. But, generally speaking, her forbearance in the face of an onslaught of strange fauna and flora has been quite remarkable. It is one of the reasons why I treasure this lady. Thus it wasn’t completely surprising, when I walked into the house after work one evening, and she said, “Hey, go look in the refrigerator and see what you’ve got.”

Our house was in the town of Kajang in peninsular Malaysia. After graduate school, I had found myself with the opportunity to join the Peace  Corps-Smithsonian Institution Environmental Program. In Malaysia I worked as a vertebrate zoology lecturer in the biology department of the University of Agriculture (today’s Universiti Putra Malaysia). At that time, the university was rapidly expanding

Corps-Smithsonian Institution Environmental Program. In Malaysia I worked as a vertebrate zoology lecturer in the biology department of the University of Agriculture (today’s Universiti Putra Malaysia). At that time, the university was rapidly expanding  in both enrollment and physical size. Many of the biology department staff members were away in the U.S., Australia, or Great Britain pursuing advanced degrees. Peace Corps volunteers filled the void within the department until these folks returned from their graduate school experience.

in both enrollment and physical size. Many of the biology department staff members were away in the U.S., Australia, or Great Britain pursuing advanced degrees. Peace Corps volunteers filled the void within the department until these folks returned from their graduate school experience.

The commute from the university to Kajang was a short twenty-minute drive and, having arrived home, I followed Anne’s invitation to check the refrigerator. Opening the door, I noticed a large paper grocery bag sitting there. Having retrieved it, I opened the top of the bag and peered inside. There, awaiting my inspection, were the remains of a snake; a very large snake at that. The serpent had for some reason been skinned. The head and tail lie separate from what was left of the body. A glance at the scalation, particularly the huge occipital scales on the top of the head, told me that here was a most exciting rarity – the remnants of a king cobra. Of course my first question to Anne was where in the world did you get this?

The cobra in the refrigerator was a gift from a colleague who lived near us and with whom I often shared field excursions. Our friend had that

day gone to a Temuan aborigine village we often visited. He had arrived at the settlement shortly after the king cobra, now residing in our refrigerator, had been killed. Doug related that our Temuan comrade Dodong, and his wife Pakok, were sitting outside their home when they observed a long-tailed giant rat dart into a nearby burrow. To them the rat represented a prized source of protein. The idea of feasting upon a rat may take some readers aback. But, here in rural Indiana, most of us don’t bat an eye at a delicious plateful of fried squirrel or rabbit. In Sullivan County, eating a rodent or a lagomorph is not that big a deal.

Pakok ran to the burrow and, using a parang (machete), began to dig the rat from its hiding place. She had only dug a foot below the surface when the king cobra in question started to flow from the den. Keep in mind that this is the largest poisonous snake in the world; over eighteen feet is the record. The toxicity of king cobra venom is not the most virulent as venomous snakes go. Its toxin has an LD50 of around 1.7mg/kg. The LD50 represents the dosage lethal to half of the test subjects, usually mice, when it is administered in a laboratory setting. In comparison, the LD50 of the venom of the inland taipan, considered by many to be the most venomous snake in the world, is 0.03mg/kg. This is roughly fifty-seven times as virulent as king cobra venom. However, it is possible for a large king cobra to deliver several hundred milligrams of venom. The volume of the venom produced more than makes up for its lesser toxicity.

These technical numbers would, of course, have been meaningless to Pakok. She did however very clearly understand their implications. As soon as the big snake showed its head, Pakok launched a barrage of blows from her parang onto the cobras’ cranium. Once satisfied that the snake was dead, she proceeded to remove its’ head. When Doug arrived, the body of the serpent was still writhing around on the ground. She had placed a rock on top of the head. Perhaps she anticipated that those needle-like fangs might still seek vengeance even though separated from their mechanism of movement. In this respect she exhibited the uncanny practical knowledge the Temuan possess concerning the animals and plants of the natural world which surrounded them. A reflexive bite from the head of a dead snake is quite possible.

Doug knew that I would like to have the specimen for the museum collections I was building at the university. He explained his reasoning and asked about procuring the snake. Dodong and Pakok responded that he might have the head and skin. They wanted the body because the Temuan also eat snakes and this one was not going to be an exception. This is how a king cobra ended up in my refrigerator.

This particular king cobra, or at least the skin thereof, measured eleven feet in length. That is about two-thirds the length of its potential maximum. Still, an eleven foot snake, particularly one with the prospective lethality of this one, is impressive. Surprisingly, the fangs of this snake were relatively short. When I measured them, only about a quarter of an inch of tooth

showed above the gum line. The fangs of cobras are permanently erect. The fangs of vipers, in contrast, lie folded along the upper jaw when not in use. Because of this structural difference, vipers tend to have fangs which are considerably longer than those of cobras and their kin. The Gaboon viper for example has fangs nearly two inches long. As a result of this difference in fang structure, vipers usually deliver a quick stabbing strike and withdraw while cobras tend to deliver either multiple bites or chewing bites in order to engage their relatively shorter fangs.

After having received the king cobra from the Temuan, I was ever hopeful that on a subsequent visit I would be able to see a live specimen of one of these snakes myself. We occasionally trekked and camped in the rainforest, most often with Dodong and his friends Oha and Panjang. Perhaps, I thought, on one of these trips luck will prevail and I will see this king of snakes. I had been somewhat captivated by the aura of the king cobra since I was a youngster. It was then that I had read herpetologist Raymond Ditmars’ accounts of the species. As reptile curator at the Bronx Zoo, Ditmars had observed a hint of intelligence in the king cobra. He recounted how one of their captives had learned to anticipate feeding time. This snake would go to the back of its cage and, using a crack between the door of its cage and the wall, peer into the service-way awaiting the arrival of the keeper with food. Such behavior certainly required a high level of awareness on the part of those managing this snake

Alas, while in Malaysia, the only king cobra I had the opportunity to closely inspect was a captive. It was a massive specimen held by a Chinese animal dealer. As I neared the snake’s wire cage, it cautiously raised its head a little and slightly flared its hood. How different this behavior was from the more common Malaysian spitting cobra. The latter typically responds to an approach with a frenzied and spectacular display of hissing, hood-spreading, and antagonistic striking. The “king” quietly stared at my face with dark eyes that suggested an intelligent analysis of the situation. The snake radiated a self-assured, bold confidence born of its high station in the hierarchy of rainforest residents. I had the very distinct sense that, could the “king” speak, it would be saying quite bluntly, “I’ll kick your ass if you mess with me.”

The major reason that I was never fortunate enough to see a king cobra in the wild rested with the rules of bioenergetics. King cobras primarily eat other snakes (their genus name Ophiophagus means “snake eater”). By eating other snakes, king cobras find themselves at the very top of the food chain. As energy is passed along a biological food chain, the amount available at each successive link becomes, for a variety of reasons, less and less. Thus, there will always be fewer lions than wildebeest, fewer ospreys than gizzard shad, and fewer king cobras than rat snakes. They are, quite simply, comparatively rarer than other snakes.

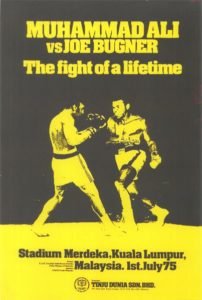

However, not long before I left Malaysia, it did appear that I might have one more opportunity to meet a king cobra. This chance revolved around, of all people, Muhammad Ali. The great heavy-weight champion was in Kuala  Lumpur preparing for a fight with his British opponent Joe Bugner. Ali was tremendously popular in Malaysia where the state religion is Islam. The boxer had a huge entourage with him and the group occupied an entire floor of the Kuala Lumpur Hilton. His stay was marked by the accoutrements of stardom and his sorties to the training arena announced by siren-blaring police escorts.

Lumpur preparing for a fight with his British opponent Joe Bugner. Ali was tremendously popular in Malaysia where the state religion is Islam. The boxer had a huge entourage with him and the group occupied an entire floor of the Kuala Lumpur Hilton. His stay was marked by the accoutrements of stardom and his sorties to the training arena announced by siren-blaring police escorts.

My office phone rang one day and it was my friend Kiew who taught at the University of Malaya. Among the crowd of photographers, trainers, and hangers-on who accompanied Ali was an avid snake collector. Thus it was that Kiew had received a call from the chancellor of his university. Ali’s friend wanted a king cobra to take home with him. Kiew was ordered to obtain one for him. Kiew in turn called me inquiring as to where he could get a specimen. I relayed the location of an animal dealer Kuala Lumpur where it might be possible to purchase a king cobra. I was a bit uneasy thinking of Kiew, who was quite inexperienced in snake handling, having to deal with a twelve-foot long package of dynamite. I advised him to use extreme caution and to be sure to enlist my help if needed. I sat, fingers crossed in excited anticipation, hoping that finally I would get to work with a living king cobra. Unhappily, it was not to be. I later found that Kiew had gone to the animal dealer who had already crated the snake for him. The serpent was passed along to the new owner without Kiew having to handle the volatile animal. In retrospect, I suppose that was a good thing. Dealing with an unhappy king cobra in restricted space is not a scenario for the novice herpetologist. Then again, maybe Kiew was simply exercising a little more common sense than myself.

In the end, this incident was certainly one I could place in my catalog of interesting life-experiences. But disappointingly, and for the final time in Malaysia, I had missed an opportunity to work with what I consider the most impressive snake species in the world – the king cobra.

(photo by Mundo Gump at Wikimedia Commons)